News

Wikipedia Won't Let You Be Forgotten

Haunted by those pictures of your undergraduate days that still show up in search, even though you deleted your Myspace account years ago? Well, if you live in the EU, you can ask Google to wave its magic wand and remove them. In May, the European Union Court of Justice ruled in favor of the "right to be forgotten," which allows people to control access to information about them on the Internet. One website rebelling against the ruling is Wikipedia, who has now created a Wikipedia page of those who petitioned for the right to be forgotten.

The ruling stems from a case filed by Spanish lawyer Mario Costeja González, who sued Google because it refused to remove links to a 1998 article about his repossessed house. The court ruled that the individual can first go directly to the source — in this case the Spanish newspaper — to request that they remove the information, but if they don't comply, then the individual can ask search engines to delete links to pages related to them if the information is "inaccurate, inadequate, irrelevant, or excessive."

The right to be forgotten has been extremely polarizing, with obvious benefits and detriments on both sides of the argument.

Why It's Better to Forget

Online privacy advocates see the court's decision as a groundbreaking step in the right direction; it offers a way to curb any extraneous or unnecessary damage online information can afflict on individuals who lead perfectly decent lives. For example, someone who committed a minor crime a decade ago, and has been on the straight and narrow ever since, can ask search engines to delete links to their online criminal records.

Perhaps the most effective application of the law is in combating revenge porn. Victims of the heinous crime now have a standard protocol to follow when trying to remove the content from the Internet, an issue that hasn't seen any clear solutions so far. Now, at least for EU citizens, Google and other search engines will be mandated to oblige victims' requests.

While the right to be forgotten hasn't hit U.S. legislation yet, some American-based companies are already fighting back.

But Some Things Shouldn't Be Forgotten

On the other side of the debate, many are claiming that the law promotes blatant censorship and violates freedom of speech. People need to remember that search engines (and the people who run them) have rights too, and forcing them to remove links from the Internet is a violation of their rights.

Not surprisingly, Google has spoken out against the EU court's ruling. "This is a disappointing ruling for search engines and online publishers in general," Google said in a statement.

In the first month after the ruling, Google received 91,000 requests for links to be removed.

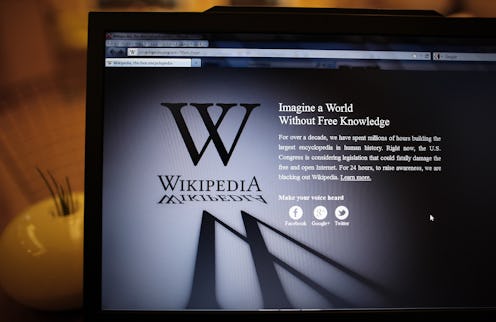

But a much more vocal opponent has been Wikipedia and its founder Jimmy Wales, who has been a longtime advocate of free speech. Wales told The Observer, "The legislation is completely insane and needs to be fixed" while commenting on the censorship aspect on BBC's Radio 4:

The biggest problem we have now is that the law seems to indicate Google needs to censor links to information that is clearly public interests—links to articles in legally published, truthful new stories.... That is a very dangerous path to go down, and certainly if we want to go down a path where we are going to be censoring history, there is no way we should leave a private company like Google in charge of making those decisions.

How Wikipedia Is Fighting Back

If you can't reverse the ruling, then have fun with it, right? That's what Wikipedia seems to be doing now with its page dedicated to all the known people who petitioned for the right to be forgotten. So far, the page lists Mario Costeja González, the Spanish lawyer who inspired the ruling and who ironically has become much more famous online; Greg Lindae, a private-equity investor who petitioned to remove a 1988 article that reported Lindae had attended a tantric sex workshop; and Max Mosley, a former Formula 1 boss who petitioned over a News of the World article that claimed he had Nazi-themed S&M orgy with five prostitutes.