Fashion

Mom, I Love You. Please Don't Starve Yourself

I come from a fat family. Everyone in the four generations that I have personally known has been, or is, overweight or “obese." We have all dieted over and over again for decades, comparing notes, congratulating each other on our “successes” and consoling one another on our “failures."

In the last months of my nana’s life, before she was diagnosed with terminal breast cancer, I was on the Slimming World diet. She was on Jenny Craig. I would call her every Tuesday evening and we would talk about how we’d done that week. We didn’t know she already had the cancer, and it would only be 11 weeks from her diagnosis until her death. All the while, she was on a diet. So yes, she did lose the weight; but it had nothing to do with Jenny Craig, and she was in too much pain to care about it either way.

My mom has been fat for as long as I can remember, with the exception of a couple of years in my early twenties (which I will go into later). As a child, other children would tease me because of her size, and to be honest, I really resented her for it. She was desperately unhappy with her body, and throughout my childhood I saw her try every diet on the market. Like most people, 12-year-old me thought that it was her own fault. She ate too much food, didn’t move enough, didn’t "try hard enough." Whatever the problem was, it was her mess, and she was failing at resolving it.

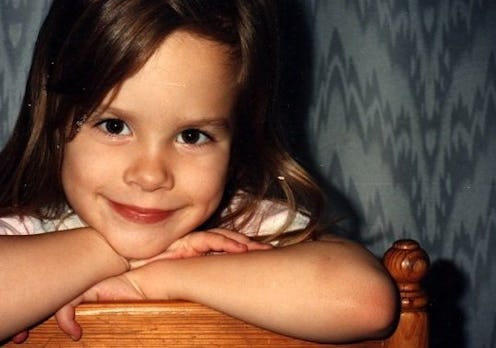

Food was a comfort — a faithful friend who would always be there for her (and later for my sister and me as well). My parents divorced when I was around five years old, and mom became a single parent of two toddlers. Determined to show us that anything was (and is) possible, she went back to school, gaining a degree in psychology. I can still remember accompanying her to lectures and copying pictures and diagrams down from the board. She was incredible.

She was also incredibly depressed. A motorcycle accident in her late teens had left her an amputee (her first and second toes on her right foot were crushed and had to be removed). This had destroyed her career plans and left her unable to walk unaided for two years. At the age of 21, her father died suddenly one day at work — just before she was to marry my father. By 29 years old, she was a divorced, single parent of two young daughters. And when she was 32, and I was 8, my father was killed in an accident on a road whilst on a business trip abroad. Though he was no longer her husband, he was, of course, still father to her two daughters. And the emotional connection had remained strong.

All of this tragedy and hardship added up, and was, understandably, very difficult for her to overcome. Even when she met my step father, and life seemed to get better, things weren’t quite right. Depression and comfort-eating have been constants in all of our lives, along with food-related guilt, body hatred and feelings of inadequacy.

I can remember myself at six or seven years old — attempting to comfort her with feeble remarks about her being “plump, not fat." Such comments were half-hearted and I am sure that much was obvious. I loved my mom so much, and I wanted her to be happy. But there was always that niggling feeling that she was the one to blame for her own misfortunes. Looking back now, that seems so harsh — and it completely contradicts my current point of view. But worryingly, I think it is closer to how she feels about herself to this day.

For the majority of my life, my mother tried very hard to ensure that my sister and I did not become overweight. She had been an overweight child herself and had suffered merciless bullying. She did not want that for her daughters, of course. The thing is, though, I was always an easy target regardless, and bullies found other things they could use to taunt me — even the premature death of my father. Kids can be cruel. Like all humans, they can be really cruel.

For the most part, my mother was successful in keeping us slim — we were both very active kids and loved to run around and play with our friends. We didn’t own a gaming console and were lucky enough to have a garden to play in (not to mention a large field nearby). We loved to cycle and swim. And we even took aerobics classes for kids. My sister loved soccer and I loved to dance. Our diets were probably a little high on sugar, but we were constantly doing something, so it didn’t seem to cause any problems (apart from a touch of hyperactivity, perhaps).

Despite my mother's best efforts, I wouldn’t say we had a very balanced diet, particularly as we got older. More and more frequently, and as my mom's depression worsened, meals were ordered in rather than cooked. And I’m ashamed to say that we never offered to help. By the time I was in my mid teens, food had become part of a coping mechanism, which I rely on to this day.

I attended my first Slimming World class around the age of 16. I was a size 14, below the UK average, but I felt enormous. I dreamed of being petite, with no boobs, no hips and a flat behind — of being able to wear anything I wanted without fear of being “too fat to wear that." The ultimate wish? To be able to go braless. Even at 17, I was convinced that my boobs were too saggy, my belly was too big, my thighs were too wide. I would stand in profile in front of the mirror and suck in my stomach as hard as I could, trying to see if I could see my ribs protruding.

We went on vacation to Turkey once. It was my first trip abroad and I was so excited. I had heard that the clothes there were super cheap, and my mom had promised we could go shopping. Once there, I discovered that hardly any of the clothes were big enough for me — and although I wore a bikini by the pool, I felt painfully self-conscious the entire time. I actually remember a woman who was staying in the apartment next to ours telling me that she wished her body looked like mine, and I genuinely thought she was insane. I was 16.

I feel so saddened when I think about the amount of time that was lost to these feelings of inadequacy — feelings that my family still battle with today, and that occasionally I do too. I left home at the age of 19 to go to university, and it was around that time that my mom heard about a very low-calorie diet called The Cambridge Diet. The meal plan consists of living off of sachets of sweet or savory powder and fake chocolate bars, which amount to up to 500 calories per day. You do not eat real food for weeks at a time, but you lose weight. Mom thought this would be the answer to all her prayers, if she could stick to it. Whilst on the Cambridge Diet, I remember my mother having sticks to pee on that would tell her whether or not she had reached ketosis. This diet, like so many before and after it, literally asks you to spend more money per week on it than you would on actual food. So that you can starve yourself instead — meanwhile shutting down your metabolism so that your body begins to consume itself.

My sister and I have both tried it as well, following in mom's example. I did it for two weeks and lost 15 pounds. The side effects were too gross to go into now. My sister had an even worse time, getting up one night to get herself a glass of water and fainting in the kitchen. Fortunately, I was awake and heard her fall. But the experience was, and remains, scary for us both. It didn't, of course, stop my sister from staying on the diet for one more month.

Mother lasted longer. She stuck to it for a year, and lost a total of around 200 pounds. In a year. Now, that might sound like the ultimate success. How amazing to lose so much weight so quickly! Isn’t it great to get healthy like that? But that’s just it; it’s not healthy at all. People who are underweight are hospitalized for starving themselves in this way on a regular basis. But when a fat person does it, it is to be applauded. They should feel privileged to spend the majority of their wages on such a "successful" system, after all. To be frank, it is a system that makes me incredibly furious.

I am not a doctor, but I do know that people who lose weight at this speed are not healthy. They are also left with large amounts of excess skin, which are just as psychologically damaging, if not more so, than the fat they were carrying previously. I remember my mom saying she felt as though she had “gone from being one kind of freak, to another." And she had starved herself for a year, paying thousands to a diet company, in order to achieve this "evolution." The only option available to people with this kind of loose skin is cosmetic surgery, which puts the body through even more trauma and pain. And for what? To be healthy? None of this seems healthy to me — not in any way.

Within two years, my mother had gained back 100 pounds. The diet had ended, and she allowed herself to eat actual food again. But her metabolism had been switched off for too long, and the diet had not addressed her relationship with food in the slightest. The gain was rapid and devastating for her. When this happens, the dieter blames themselves for failing at dieting; for not having enough willpower; for being too weak. My mother starved herself for a year — willpower is not the issue here. The issue is that the diet was not designed to achieve sustainable weight loss. The results are meant to be fast, and subsequently, dieters love the praise they receive as the weight quickly drops off them. But when they stop starving and start eating, everything changes again. It is traumatic and it is unfair.

Even now, eight years after she first began Cambridge-ing, she is considering trying it again. I have begged and pleaded with her not to. I have tried to reason that starvation is not healthy — that she has sent money to third world countries for years to prevent starvation, and yet she is willing to spend even more money to inflict it upon herself. But she won’t listen. All she can see is a body that is too fat, and a fast solution that will give her back the body she thinks she wants (except it won't, because the excess skin will still be a problem).

I have spent a lifetime watching the woman I love more than anyone else on this Earth punish herself for the way she looks, and it breaks my heart. I've also spent more years than I care to count hating myself in exactly the same way. I have no problem whatsoever with people wanting to lose weight. If you think it will make you happier (truly happier), then I say go for it. But please, don’t starve yourself. Don’t punish yourself. It is just not worth it.

You are beautiful. You are loved. And you are worthy. I may not be a doctor. I may not be a nutritionist. But I know these demons well — so this is me telling you that you do not have to hate yourself.

Images: Emily Louise Holton; Daniel Yates