Books

Don't Write Kickass Women. Write Kick-Heart Ones.

My first book came out 11 years ago. So, I’m reasonably certain that I gave my first Real Live Big Girl Pants Authorial Interview around that time, as well. Thus began my own particular Unexpected Journey, which, naturally, involved several trolls, a number of second breakfasts, long walks on the swamp, and answering questions about how to write “strong female characters.”

I have always been asked about writing women. I have always been asked about writing strong women. It comes with the territory — I have, from the first stories I ever laminated into a neon blue Trapper-Keeper to submit to my 4th grade writing contest, written about women and girls and even female griffins/unicorns/ring-tailed lemurs. Call it narcissism; I am, after all, a woman. But I am a woman whose mother is a feminist political science professor and whose father is in advertising, so I tend to look at everything with the kind of side-eye you learn at the knees of people who know, on the one hand, how the world gets sold to us, and on the other, how to sell the world.

I have never once been asked how I write male characters, nor how to write strong, kickass male characters, nor whether I’m concerned about making the men in my books vulnerable as well as tough.

I have never once been asked how I write male characters, nor how to write strong, kickass male characters, nor whether I’m concerned about making the men in my books vulnerable as well as tough. Yet so often, our culture at large seems to peer into novels (and movies and television) as through the bars of a cage at the zoo. Here we see the endangered strong female protagonist in her natural habitat! What strange markings she has! What goes through the head of such a bizarre creature?

And because she is treated, not as an obvious citizen of Literature Mountain, like the male protagonist, but as a rare and almost alien beast, we can gather round and poke at her, examine her teeth and her eyeballs and her motivations. Well, yes, she’s strong, but what if she’s too strong? She is capable and clever and brave, but is that really believable? She saves the day, sure, but who is she going to make out with?

The “kickass” female character has been discussed so often and with such energy that the phrase has almost become axiomatic. Yet equally dissected is the idea that we have swung too far toward “strong” and away from vulnerability, complexity, nuance. It’s an awful lot for one load-bearing protagonist. And this, I suggest, is the problem.

If there’s only one woman in a story, she ends up having to stand in for all women. It’s fine to have a female character who is emotionally fragile, manipulative, and physically helpless. Miss Havisham is an amazing character, and all that is true of her. The trouble comes when that woman, whose traits are a heap of traditional negative female stereotypes, is the only one around. That’s when it starts to feel like the author is saying something about What Women Are Like. The world is half female. Stories where only one girl is allowed in the Player Character club feel like they have a footnote that reads: If you’ve met one lady, you’ve met them all, am I right?

If there’s only one woman in a story, she ends up having to stand in for all women.

Player Character is a gaming term meaning a character who can be played by the human user, with whom we identify, who can make choices, move the story forward, take actions that matter significantly to the narrative at large. Non-Player Characters (NPCs) are people the PC meets along the way, who cannot be played by the gamer and whose actions are peripheral, pre-programmed, reduced to saying things like “I have some swords to sell” and “Would you like to stay at the inn, good sir?” It’s a useful shorthand for characters with agency and without. Rarely is there really only one woman in a story’s entire universe, but very often, there is only one who really matters — the Hermione, the Katniss, the Princess Leia, the Black Widow — the one girl in a group of boys, the chosen one, the love interest, the lone girl warrior.

And the trouble is, when you’ve only got one, she has to be everything to everyone. Strong and vulnerable and sexy (but not too sexy) and shy and smart (but not too smart) and good-hearted but also conflicted and dark, independent and devil-may-care but maternal and nurturing, confident and funny but not arrogant or upstaging — it’s exhausting. No real person is like this, which is why we tie ourselves in knots over creating the “right” kind of female character. The solution is simple: more feet on the ground.

Joss Whedon has an incredible reputation as a feminist writer. It’s not because his female characters are perfect or un-problematic. It’s because he gave us so many of them. In Buffy, Firefly, even the deeply troubling Dollhouse, he presented a number of different women in different roles, with different personalities and problems. Buffy can just be a flawed, interesting, even occasionally off-putting, person, rather than simply the Girl, because Willow and Cordelia and many, many others are also there, being people, expressing the wide variety of good and bad that occurs in real human women, just like real human men.

The real question has never been: How do you write strong female characters? The question has been: How do you write strong characters? Because the female part is not a modifier that has to be balanced out by armor and swearing. I actually do spend quite a bit of time worrying about whether my male characters are vulnerable and emotional enough — because that’s what it means to write an interesting character. Invulnerable and emotionless isn’t interesting, regardless of gender. No one loves Spiderman because of how hard he punches. They love him because he punches really hard while actually being a skinny geek who’s having a really hard time getting over his uncle’s death. It’s the combination of strength and weakness that makes someone feel real. Often when we talk about complexity, we are talking about weakness. Might, while forceful and active, is rarely complex. An interesting weakness will endear a character far more than an interesting strength. Everyone is weak sometimes. Everyone knows what it feels like to grieve, to need, to yearn for something we can’t have, to feel alone, to lose hope, to try to claw there way up form nothing into something better. Only some of us can punch really hard.

I actually do spend quite a bit of time worrying about whether my male characters are vulnerable and emotional enough — because that’s what it means to write an interesting character.

I’ve never set out to write kickass characters. Not even in my neon blue Trapper-Keeper. I try to write kick-heart characters. Women and men and girls and boys who feel the world piercingly, who want things fiercely, who don’t always know what’s right, who use their outside voices to try to connect with others and embrace the often frightening things around them, without being walking greeting cards — and that’s harder than you think. Emotional honesty is still kind of a radical thing, on Literature Mountain and off. Sure, a good roundhouse kick to the face of evil may figure in my books sooner or later. But I’d rather go for a roundhouse kick to the heart.

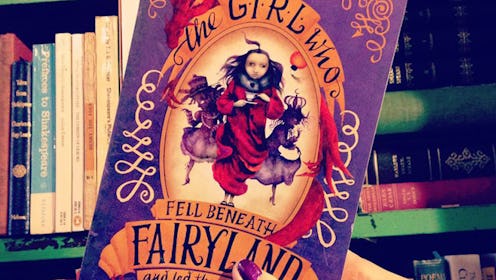

Image: jenvcampbell/Instagram; Giphy