Life

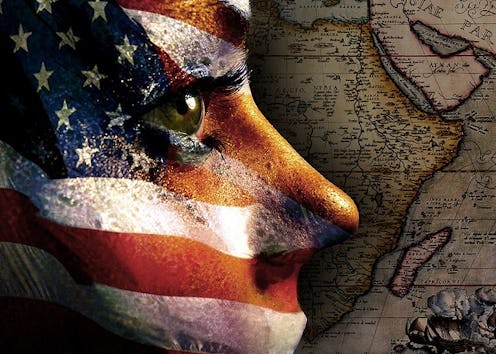

What It's Like Being An Invisible Immigrant

The news has been full of stories about the struggles of migrants recently — you've probably read a lot about refugees from Syria and Iraq, and may know something about the millions of other people worldwide who migrate from their home countries for thousands of reasons each year, from fleeing war and prosecution to pursuing an education, a partner, a better life for their kids, or just a cool experience. The sheer range of migrant experiences can mean that those on the luckier end of the spectrum may feel they should stay quiet about the experience, even though they too have experienced difficulties. But being a migrant is always complex, no matter how simple it might seem, and we all stand to gain from hearing about as many different migrant stories as possible.

I've been an immigrant since 2009, when I came to England from Australia, in order to attend a master's degree program for two years. Come 2015, I'm still here, married to a Welshman, with a house and a large, irascible adopted cat. The problem isn't that I stick out: it's that I don't. I'm one of the invisible immigrants, the people who migrate across continents but manage to assimilate easily, speak the same language, and even share some of the same cultural tastes of their adopted country. Our stories tend to be less commonly told. I know that I'm lucky — not only compared to the countless refugees seeking safe shelter worldwide, but compared to the many immigrants who face prejudice, hate, and violence due to their perceived "difference." Here's my story.

1. Nobody Believes That Invisible Immigrants Have Legal Difficulties

I just had to send off a 300-page visa document in order to not be deported. It cost thousands of pounds in attorney fees and likely took several years off my life. But this comes as radical news to many people, who imagine that because of my outward ability to assimilate — I have white skin and I'm English-speaking — or my degree of education, it's "easier" for me to stay in a country, or that my status as a migrant is more secure. Not true.

I face the same threat of deportation, the same uncertainty, and the same treatment by authorities if I step out of line as any migrant. This is the reality of invisibility: people erroneously believe that you somehow get special treatment because you "seem" more local, even though legal policy is not built on how you "seem." The truth is that you're subject to the same demands as all migrants, and that can make a scary situation (like the prospect of being deported) feel even more isolating.

2. People Who Are Anti-Immigrant Tell You "I Don't Mean You"

When people say "immigrant" in the place where I live, more often than not they are using the phrase as a way to say "non-white," "Romani," "undocumented Latino," or some very specific group currently being depicted by certain politicians and members of the press as a job-taking, security-risking, benefits-stealing threat. They aren't railing about how someone like me, a white girl with a doctorate and an accent more English than the local vicar, is trying to take their job. Which means I'm often in the utterly infuriating situation of sitting listening to anti-immigration rants, pointing out that I am in fact an immigrant, and being told it "doesn't apply to you, dear". Er, yes, it does.

In terms of sheer distance from my homeland, I'm as foreign as it gets. If you're anti-immigrant and insist that you don't mean me, then you actually mean "migrants in particular racial groups I don't like". Let's be really clear, here.

3. Invisible Immigrants May Feel Guilty About How Easy We Have It

Being a migrant means doing a lot of comparisons. I feel a perpetual mix of gratitude and horrible guilt regarding how easy my migration experience has been compared to many others, because of my linguistic and cultural links to my adopted country. I haven't had to learn how to use local services from scratch, navigate legal jargon in a foreign language, been discriminated against because of my accent or ethnicity, or had my professional qualifications unrecognized. My migrant experience has been lonely, uncertain and often very scary, but it's also been manageable — and not because I'm any better or more qualified than any other migrant. I just got lucky.

4. Our Countrymen May Not Recognize Us Anymore

Immigrant status is a peculiar thing. If you assimilate as much as I have, even accidentally (being with a Welsh dude for six years will rub off on you, eventually), you start to lose what makes you visibly foreign, and that can be a very difficult thing to deal with emotionally. Australians no longer recognize my accent; I've been asked, when booking a flight back to Sydney, whether this is my first time visiting. It's a discombobulating experience, and actually quite an upsetting one. Once you really leave, you can't ever go back.

5. It's Wonderful To Be Part Of The World Community Of Migrants

Migrants play a big and important role in the world community. The global economy and telecommunication across the planet have made the movement of people more pronounced, and then, of course, there are the wars and upheavals that have driven millions to seek refugee status in new places. If you live in a major city or a university center, wherever you turn, there's going to be someone far from home.

And that's a lifeline. We're all in this together: when I had to have the English banking system explained to me, when I couldn't understand the coins, when I didn't understand anybody's pronounced Somerset accent, other migrants came to the rescue. Or to sympathize. Both are important.

6. We Have No Idea Where "Home" Is

To be honest, this isn't entirely true. Home is wherever the aforementioned dude and irascible cat are. But breaking links from one place and putting down roots in another isn't as easy as it might seem. Being a visible "migrant" has its own pluses: you often find your way to your own cultural community relatively quickly. Us more hidden types, however, are meant to assimilate and make our own way, and actually end up with less cultural support. I have no more family ties to Australia, the country that I live in does its absolute best to throw me out if I make a math mistake on a hundred-page document, and everybody assumes it's all easy for me.

So, make sure to keep the many visible and oppressed migrant and refugees communities in your thoughts, but remember that invisible immigrants aren't just taking an extended vacation in your country, either; they, too, are struggling to be allowed to call a new place home.

Images: Jewish Centre For Israel, Minnesota Historical Society, Takoma Bibelot, Mark Rain, Jorge Luis Perez/Flickr