Life

Why You Grieve After A Celebrity's Death

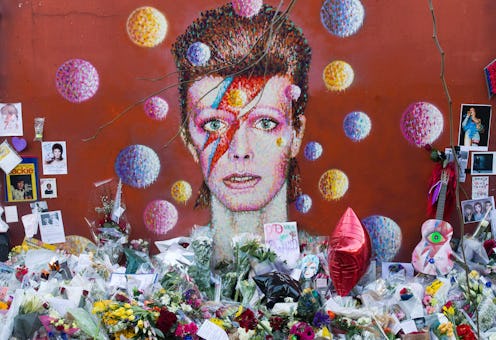

Last week, the unexpected deaths of music legend David Bowie and beloved actor Alan Rickman had many of us shedding tears for two men we had never met. Grieving for a celebrity is a strange feeling — we can experience a profound sense of loss and sadness, but for someone with whom we didn’t interact, someone who didn’t know who we were. How does that work?

In an article for HowStuffWorks, Christian Sager explains that this phenomenon is a product of “parasocial relationships.” In the 1950s, sociologists Donald Horton and Richard Wohl used the term “parasocial interaction” to describe people’s deep feelings of closeness to celebrities they’ve never met or with whom they’ve had very limited interactions. These audience-celebrity relationships are no less intense for being one-sided. In fact, the very one-sidedness of these relationships is often central to the appeal of the celebrity: Fans can identify with the public figure, and experience an idealized relationship involving unconditional acceptance and support — without the difficulties inherent in real world interactions.

Parasocial relationships can be powerful, identity-forming forces in our daily lives, so it’s no surprise that when a beloved celebrity dies, fans grieve that loss. But the shape that grief takes is, by necessity, different from how we would mourn the loss of loved ones in our actual lives. As Sager writes,

When someone in your life dies, your process of mourning helps maintain and reconstruct who you are. But in a parasocial relationship you're not invited to the funeral. You're not privy to the disposal of the body either. You have none of the usual outlets to express your emotions. So in a community of mass consumption, how do we process death?

Sometimes we mourn celebrities by interacting with other mourning fans, something that social media has made particularly accessible. In the wake of Bowie and Rickman’s deaths, fans flocked to Twitter, Facebook, and Tumblr to pay tribute to the deceased, and grieve — virtually — alongside each other. In 2012, Glenn Sparks, a communications professor at Purdue University, explained,

By interacting with others who also had such a parasocial relationship with the deceased, we get to engage in a kind of mediated family that collectively gets to express its big group emotion to the loss.

In a 2012 article, professors Scott Radford and Peter Bloch describe two other ways that fans cope with the death of a celebrity: “Introjection” and “incorporation.” Introjection involves fans attempting to “relive” their experiences with the celebrity. We can see this behavior, for example, in SNL’s decision to replay David Bowie’s 1979 performance on the show the past weekend, and in articles reminding us of Alan Rickman’s most loved scenes. Incorporation involves fans’ increased interest in material objects associated with deceased. As Sager points out, this might mean that a fan jumps to buy Bowie’s final album, or, in a more extreme case, that a fan attempts to acquire objects that the celebrity actually owned or touched. These things can take on the status of sacred objects. (There’s a reason that, at an auction in November, someone paid $137 thousand for a sweater once owned by Kurt Cobain, and another person paid a cool $2.4 million for John Lennon’s acoustic guitar).

Although spending millions on a guitar may be extreme, fans’ reactions to Bowie and Rickman’s deaths, from sharing memories and videos on social media to decorating Platform 9¾, are, in fact, healthy ways of coping with losses that — despite the distance between fan and celebrity — are nevertheless both real and painful.