News

How Crowdsourcing Could Help Exoneration Cases

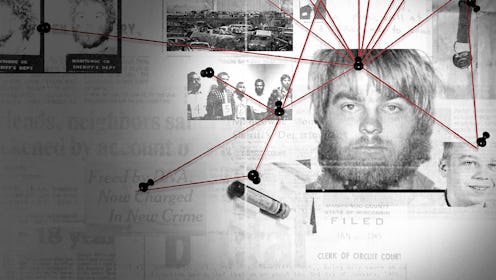

After Making a Murderer ended, many people took to the Internet to discuss details of the case and try to make sense of it all. The interesting thing about the nationwide obsession with the Netflix series is that people from all backgrounds — not just lawyers or legal experts — became genuinely interested in Steven Avery's case to the point that they tried to find alternative theories to exonerate him. The rise of the Internet's role in coming up with these perhaps overlooked theories is relatively new to legal cases and it could have a significant impact on how some cases are handled in the future. Speaking as a representative of the Wisconsin Innocence Project, Co-Director Carrie Sperling said crowdsourcing might be helpful in freeing innocent people who have been wrongfully convicted.

The Wisconsin Innocence Project is the same organization that helped exonerate Avery from his wrongful sexual assault conviction in 2003. As co-director of the organization, Sperling has seen a lot of cases similar to Avery's, although none have gained as much national notoriety as Making A Murderer. In her interview with Observer.com, Sperling talked about his unique case and how the public's involvement (through Internet discussions and theories) could actually be a good thing for future exoneration cases — even if it goes against everything traditional lawyers are taught.

At the end of December, a Reddit thread for Making a Murderer theories emerged, proving just how many alternative theories the Internet could come up with in a short amount of time. Opening up cases to the public, and giving so much access to media, is in direct contrast to what lawyers learn throughout law school and their careers. In her interview, Sperling talked about the difference in how cases are handled now, specifically with the rise of the Internet, and how that contradicts everything she learned in the past.

It cuts against everything we learn as lawyers. You know—confidentiality, not disclosing your strategy too early, and keeping the facts to yourself until you’re ready to present them. It cuts against so many things that we are taught to avoid, especially the media being involved. Many defense lawyers don’t want the media involved, period.

It's interesting to consider that the media is exactly what caught the Making a Murderer filmmakers' attention in the first place: the 2005 New York Times article about Avery got them interested enough in his case that they embarked on a 10-year journey producing this documentary series. Recognizing this, Sperling said she now sees how crowdsourcing and giving media additional access to these cases could help lawyers and journalists find better, alternative theories to solving these cases.

But you see how it’s already helped [Brendan] Dassey and Avery, because the documentarians got interviews with the legal team, and even Avery’s family. In the end, I think the media access has really helped their cases.

Without access to Avery's family and his legal team, the documentary would have lacked a lot of crucial information. What's more, the public would've been missing this information, which would have denied them the ability to form their own hypotheses as to what else could have happened that day with Teresa Halbach.

Sperling's biggest argument for crowdsourcing legal cases to the public is that it could potentially speed up the criminal justice process, which typically takes one to 10 years for litigation to be completed, according to the Innocence Project. Also, opening these cases to the public allows so many people who aren't in legal professions to participate in the process, which could introduce invaluable insights to the cases.

Theoretically, we could investigate so much more thoroughly and more quickly if we would just open the investigation up to people who are interested in solving a mystery and freeing an innocent person...I was watching on the Internet about what people are saying about the Avery case. I saw some of the different scientific concepts that came up, including details regarding the burn pits and temperature and detailed evidence collection. The documentary opened up the evidence in the case to the digital world’s power...

Sperling said in her interview that she expects many future cases to involve crowdsourcing and more media access. "I’m excited to think about the speed and the power of the Internet to investigate potential innocence cases much more quickly," Sperling told Observer.com. "If you know you need an expert for something, maybe you can throw it out there to the world, and see what kind of help the collective intelligence of the internet can provide."

Images: Netflix