Bustle Exclusive

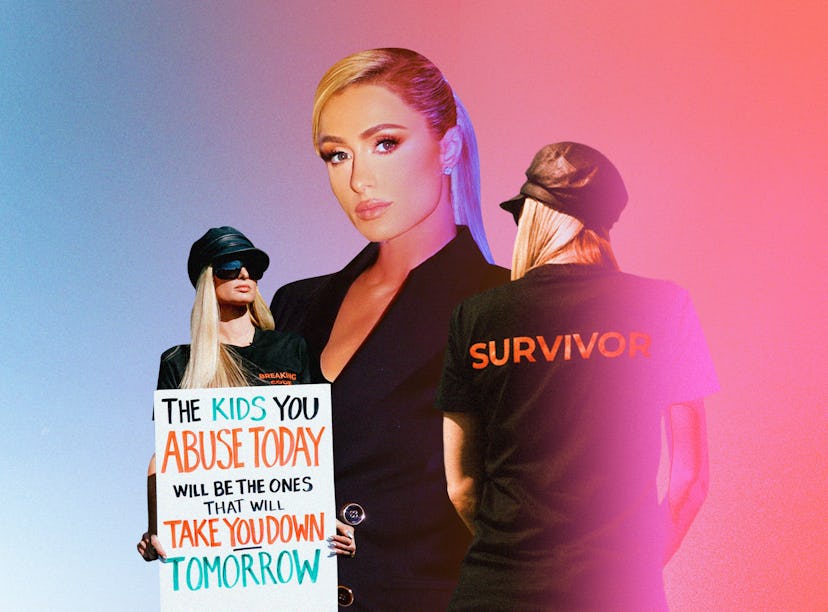

Paris Hilton Is Taking On The Troubled-Teen Industry

As a child, the heiress witnessed the industry’s horrors firsthand. Now, she’s fighting back.

When Paris Hilton began speaking out about the alleged abuse she endured at a supposedly rehabilitative boarding school, it’s not hyperbolic to say that she changed and saved lives. It was 2020, and the unregulated troubled-teen industry — a network of private, for-profit schools, wilderness programs, and institutions to reform “troubled” youth — was still largely in the shadows. Since it was formed in the ’60s, more than 145 children have died while in the industry’s care, and even more have reportedly disappeared, yet there had been few consequences for those in charge and little to no public outcry. Until Hilton released her bombshell 2020 documentary, This Is Paris.

“I just want people to understand that these types of places exist, and that there are hundreds of thousands of children being sent to these places every single year,” Hilton tells Bustle. “There are children who are dying in these places, and [people are] physically, emotionally, psychologically, and sexually abusing children [in them].”

In the documentary, Hilton details the time she spent in the late ’90s at Provo Canyon School, where she alleges that she was sexually assaulted under the guise of a gynecological exam, as well as subjected to many other forms of physical and emotional abuse.

And since the film’s release in September 2020, an entire generation of former TTI students have come forward to share and reclaim their stories of negligence and abuse. Hilton has taken a leading role in the movement, joining survivors and allies who call for change — people like Caroline Cole, a policy consultant who works with Hilton on advocacy efforts, and Rebecca Grone, the newly appointed head of impact for Hilton’s 11:11 Media.

In 2022, Cole and Grone created the Trapped in Treatment podcast, each season of which focuses on a different treatment facility, or group of programs, within the industry. (Season 2 drops today on the iHeartRadio app and all other podcast platforms.)

“I just keep thinking about how when I was a teenager, if someone had [stood up] for me, I would’ve been the happiest person on the planet,” says Hilton, who produces the podcast. “So to be able to do that for these [teens] is the most important work I’ve ever done. This is my purpose in life now.”

In addition to the podcast, Hilton, Grone, and Cole have appeared on Capitol Hill to introduce a federal bill, traveled the country meeting with local legislators, and held press conferences, all in the name of reforming this industry.

Below, they share more about their advocacy work — as well as what’s in store for the second season of Trapped in Treatment.

Paris, thanks to you, the troubled-teen industry has become part of the cultural conversation, but many people still have a limited understanding of it. What’s one thing you wish everyone knew?

Paris Hilton: That the marketing is so deceptive. My parents received this brochure [for Provo Canyon School], and it had children smiling, riding horses, and it just looked like this really beautiful, happy place. But none of those photos were even taken at the school. It was all stock photos. They’re selling these families a lie during the most vulnerable time.

It can be a difficult time when a parent has a teenager who starts rebelling and they don’t know what to do. So it’s turned into this huge industry that so many children and families have been victim to. I just want people to know that’s happening behind closed doors.

There’s a misconception that because they’re expensive, they must be good.

Rebecca Grone: A really important point. Also, it isn’t just wealthy families paying for this level of treatment. School districts and state agencies are paying to place youth from child welfare and the juvenile justice system [in these programs].

This season of the podcast centers on WWASP, a group of therapeutic boarding schools, wilderness programs, and other behavior modification programs founded by Robert Lichfield. It has come under fire for allegations of physical and sexual abuse. How did you land on this focus?

Caroline Cole: We started [Season 1] with Provo Canyon School, which is one of the facilities that Paris went to. And Lichfield actually started as a dorm parent at Provo Canyon School. He worked there for over a decade. So when he created WWASP, he was going to do what he did at Provo Canyon but make it “better.” I put that in quotes, because we ask the question, “Better for who? Better in what ways? More profitable?”

In Season 2, we’re following the creation of WWASP — not only because I’m also a WWASP survivor, [as is] our researcher, Chelsea Maldonado — but because WWASP had an impact on the industry as a whole.

Once you started digging into WWASP, what shocked you most?

Grone: For me, as a nonsurvivor and someone who hasn’t been a part of this community for the past few decades, [I’d wonder], “Where are these abusers now? Were they held accountable?” And unfortunately, the answer is no. It was shocking to understand that the laws in our country still allows folk who have abused children to continue that horrific cycle. That’s something we dive into [this season].

When doing my own reporting on this industry, survivors I spoke with were often grappling with their trauma. But unfortunately there isn’t a “guidebook” for how to interview vulnerable subjects without triggering them. How did you two approach this?

Cole: It was important to make sure we [approached interviews] in a way that was sensitive, ethical, and survivor-led. So outside of Rebecca, 11:11 is led by lived-experience experts like myself. We also identified interview candidates who were already telling their stories, people who felt comfortable acknowledging and reckoning with their own experiences. We sent questions ahead of time, letting them know what we’d be diving into. We let them mark off any questions they were not interested in exploring.

When you first tell your story out loud, it can feel so vulnerable. It feels like you’re naked in front of a room full of people. We wanted to make sure folks were not only supported [during the interview] but afterward too.

You’ve all been very involved in championing the Stop Institutional Child Abuse Act, which would create federal oversight for the troubled-teen industry. But you also stress it’s actually bills on the state level that could create the most change.

Cole: States provide direct licensing [to the programs] and are responsible for enforcement and taking action against facilities. They have a lot more direct power and control when it comes to the quality of care in these facilities, while the federal government can play a strong role in information-sharing and transparency.

Grone: We’ve worked on eight state bills and have successfully passed laws in those states. Caroline and Paris also had the opportunity to share their stories [in these hearings, which] has accelerated policy change. We have two bills in state legislatures right now, in California and New Hampshire, which have passed the Senate. We’re hoping those will be signed by their governors.

As for the Stop Institutional Child Abuse Act — which has so much bipartisan support in Congress — every single day that we wait to get that passed, we’re doing a disservice to the kids who are still dying in these facilities.

Paris, I know you were just in Jamaica supporting those who spoke out about the Atlantis Leadership Academy. What can you tell us about that experience?

Hilton: When I heard that there were seven American boys in Jamaica who were going to court to testify about the abuse they’d suffered — and they didn’t have their families with them, they had no one there to support them — I got right on a plane. I flew there to advocate for the boys, bring them clothes, and let them know that we believe them. That they aren’t alone. We also supported them in getting legal assistance and referring them to law firms, so that they could seek justice.

It’s just so wrong that they are being shipped internationally and, essentially, being warehoused in these facilities abroad. So it was heartbreaking to see the boys and how broken they looked. But it also made me happy that when they saw me. They just were like, “Thank you so much for coming. This means the world to us.”

Paris and Caroline, what has been the most cathartic part of engaging in this work?

Hilton: It’s been the most healing experience of my life. People come up to me on the street and say: “I watched your documentary; I read your book. I was at these schools and my family didn’t believe [what happened to me]. But now, since I showed them what you talked about, they finally believe me, and I feel like I’m finally being validated for what I went through.”

Cole: It’s so rare that people are able to create systemic change in systems that have harmed them. So I feel so incredibly honored and privileged.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

If you or someone you know is seeking help for mental health concerns, visit the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) website, or call 1-800-950-NAMI (6264). For confidential treatment referrals, visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website, or call the National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357). In an emergency, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988, or call 911.

If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, you can call the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673) or visit hotline.rainn.org.