Books

Q&A: Where Are All The Good Literary Magazines?

How many literary magazines do you have to sift through to find a good literary magazine? Just one, if it's dedicated and obsessive enough — and that one-stop-shop is exactly what Becky Tuch has been curating for the past six years. Her brainchild, The Review Review, is a site designed to review literary magazines — the good, the bad, the beautifully hand-drawn, and the poorly edited. If you are a literary magazine, then no matter how big or small your readership, The Review Review will find and review you with grace, compassion, and unflinching honesty, and writers all over the globe will use The Review Review's review to determine if they should trust you with their precious work. Sound like a plan?

Tuch started the site in 2008 when she began to feel like her own personal submission process was futile — and that she was submitting to literary magazines that she'd never care to read. She found it sobering that many of her writers friends felt and acted the same way, hoping to be published but unwilling to subscribe. Thus: The Review Review. It's a comprehensive guide to literary magazine perusal, where you can read honest reviews of hundreds of magazines along with useful magazine listings, interviews with editors, and a large helping of publishing tips designed to help writers on their merry, published way.

Tuch and I spent a few hours frenetically chatting about the literary magazine scene in a multi-colored Google Document, and here are the illuminating results of our conversation. Read on to find out about the booming Lit Mag Movement, the plight of the lit mag editor, and whether or not The Review Review offices have pizza.

BUSTLE: Let me just tell you my immediate reaction to your website's About page: I feel the exact same way!!! I used to submit blindly to literary magazines without reading any of them. If a story got picked up, it was often by a lit mag that wasn't terribly good and then I'd kick myself for not having a better submission process. But underneath it all was that nagging sense of guilt: If I don't read these magazines, who will read my story? The Review Review has clearly hit a (good) nerve: you have 7.5K followers on Twitter and almost 4,000 subscribers to your weekly newsletter. Obviously, thousands of writers feel the same way you and I do. So, do you think you've changed the lit mag game?

BECKY TUCH: It would be hard to measure The Review Review’s individual effect on the lit mag world. The landscape of literary magazines has changed rapid-fire over the past decade, due to the increase in MFA programs, new technology, and many other cultural and economic shifts big and small. I don’t know that we’ve changed the scene so much as been part of an overall Lit Mag Moment.

I will say, though, that if there’s one significant thing we hope to have done it’s empower writers to have a good time and lighten up about a lot of this stuff. One of our big goals is to foster a sense of community among both writers and editors as a whole, less “We the Writers Versus They the Dastardly Gate-Keepers” and more “Hey, The Gang’s All Here, Who Wants Pizza?”...Actually there’s not much pizza on our site. But you know, some levity, playfulness, open channels of communication, a sense of all of us hanging out together and eating at the same table.

Tell me more about this Lit Mag Moment you speak of. Do you mean the proliferation of online magazines?

Yes, online magazines, the sheer abundance of them. Also, the attention to diversity in lit mags. The VIDA Count, which began a few years ago, did something very important for women writers but it also did something very important for lit mags. The Count said to the world that lit mags, and the work published in them, is vital, is relevant, is meant to be taken seriously. I would say the VIDA Count is a huge part of the Lit Mag Moment.

What’s fascinating are the many new lit mags which use identity as a guiding principle: Queer poets of color, Asian American writers of speculative fiction, Latino writers, transgender writers, gay male poets, African American women poets, lesbian writers, women writers of nonfiction…. Years ago, someone contacted me to see if I could recommend any lit mags specifically for gay writers. I could not name a single one. Now I can name ten.

Tell me a bit about the process of running The Review Review.

Thank you for using the word “process” in regards to running the site. You make it sound so organized and systematic.

The site has several key components: Lit mag reviews, editor interviews, and publishing tips. These we post on a weekly basis. We’ll post anywhere from 1-4 new lit mag reviews, one editor interview, and one article that sheds light on some aspect of the writing/submitting/publishing process. Presently, I have a crew of invaluable interns (Kelsey Leon, Danielle Dicenzo, Windy Lynn Harris, Alicia Cole, and Bernard Grant) and an amazing tech guru, Lissa Kiernan.

Then there are the hundreds of writers whose work is the essence of the site. We could not do any of this were it not for the many reviewers, tips writers, and editor interviewers who’ve all helped create the site’s content. Plus so many editors have been kind enough to be interviewed and have jumped in with suggestions, ideas, support. (I still remember Chris Wiewiora of Flyway Magazine coming up to my table one year at AWP, a total stranger whom I’d never met, and saying, “Here are all the things you should do.” His was invaluable advice.)

So, yes, I personally do many many things: Maintain the database of over 1,000 lit mags, reach out to editors to see if they’d like to list calls for submissions or contests on our site, mail out print magazines to reviewers, work with writers to edit their articles, post all the content, stay active on social media, write our weekly newsletter, write reviews, interview editors, write publishing tips. But everything on the site is the product of many people’s contributions — written content, advice, feedback, technical support, financial donations, help, generosity, and encouragement.

Often, lit mag editors are underpaid (or working for free), overworked, etc. As the founder of The Review Review, has the plight of the lit mag editor become your plight? Is this your full-time job, and if not, how do you pay the rent?

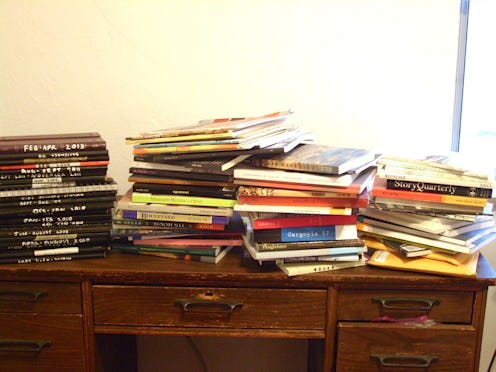

Ha. Someone needs to write a memoir called The Plight of the Lit Mag Editor. The cover might be a person with a deeply furrowed brow sitting amidst ceiling-high stacks of story and poetry submissions.

The Review Review is definitely not a full-time job. I pay the rent in the same way so many of us writers pay the rent: I teach writing workshops, I do manuscript consultations, I lead workshops at conferences. Whatever it takes. Only recently did I stop waiting tables, which I did for my first 10 years out of college. (It was actually while I was waiting on a customer that I had the idea to start The Review Review.)

I would say I have many plights, some that may overlap with those of journal editors, some that are uniquely our own. One thing we do not have to deal with, for instance, is the sting of rejecting writers. I know editors really don’t like to say “No, thanks,” to writers (in spite of a commonly held view that editors somehow enjoy this or get off on this in some way). Most editors I know are kind, dedicated, hard-working people who don’t like sending rejections any more than writers like getting them.

Most editors I know are kind, dedicated, hard-working people who don’t like sending rejections any more than writers like getting them.

We, on the other hand, really want to encourage writers to work with us, in whatever capacity they can. We rarely write the words “No, thank you” to writers.

I myself cut my literary teeth on writing art and literature reviews when I was first out of school. Writing reviews is a great way for new writers to gain skills and build publishing credentials. So we usually try to find a way to bring a writer on board, either reviewing journals, interviewing editors, writing a Tips column, or something else.

In other respects, yes, I do identify with editors very much: Tech glitches, money concerns, too much work, not enough time, hating/loving social media, trying to stay on top of emails, dealing with the occasional difficult personalities, trying to create enough time and mental space for my own writing, yup, all that is there.

Your own writing! We’ve been talking about your work as an editor, but tell me about your path as a writer. Do you have an MFA? Are you currently working on any projects?

Thanks for asking! Short answer first: No, I do not have an MFA.

Longer answers: I am currently working on a novel. The protagonist is a young girl who gets caught up in some serious mischief.

In terms of what I’m drawn to, can I just say? As far as Moments go? Is it the Moment of Badass Women or what? Seems like everywhere I turn lately another writer is exploring female aggression in ways that are truly outstanding. I just finished reading Young God by Katherine Faw Morris which, wow, just, wow. I could hijack this interview and spend the entire time talking about this book. But I’ll just say: read it.

Laura Miller just wrote this great piece in Salon about how “today’s most exciting crime novelists are women,” and she talked about Kate Atkinson, Tana French, Gillian Flynn. I’ve read just a few of these writers, but I am so excited by this development overall, this Moment of Badass and Occasionally Brutal Women. These are women who don’t just go out and cheat on their husbands or quit their jobs or travel to foreign countries to “find themselves.” These are women who know how to use weapons and who commit serious crimes. They fight psychologically, physically, and perhaps most important: Unapologetically.

Seems like everywhere I turn lately another writer is exploring female aggression in ways that are truly outstanding.

In general I’m interested in the tension between chaos and order, specifically the criminal versus society. What if society itself is the criminal? How do we reconcile our sense of personal morality with all the hypocrisy and lies around us? This is why I think teenagers are great protagonists. They are so sensitive to hypocrisy among adults. It’s almost like their getting into trouble and mischief is a form of resistance, a form of pushing back against a false and repressive social order. When you have a female teenage protagonist, you get to explore whole new dimensions of aggression and anger coupled with deep vulnerability and fear. These are the things that have occupied my mind lately.

The Review Review isn't just reviewing the great lit mags — you tackle the not-so-great ones, too. Is there value in paying attention to the under-edited online lit mags of our time? Why review the not-so-good ones?

I think it’s important to review the less-than-stellar magazines for precisely the reason you talked about in your first question: you wish you’d known that some magazines were not so great before you sent your work there.

Of course, one could say that checking out the magazine and doing your homework could keep a writer well-informed. But I also think it’s important to hold these journals accountable. I mean, come on. You’re asking writers to take time to send you their work, in some cases demanding a writer’s “best work,” and then not holding up your end of the bargain if you produce something sloppy.

A few years ago I wrote a review of a highly competitive and prestigious magazine whose issue was absolutely littered with typos. It was quite appalling, actually. They had used the number “1” many times in place of the letter “I.” The punctuation was all out of whack. Words were glaringly misspelled. After I published the review, several writers wrote to thank me. Their work had appeared in that issue and they were upset, rightfully so, to see it presented in this way.

What’s interesting to note is that occasionally a quality magazine will publish a messy, poorly edited issue and then, lo and behold, a few months later the magazine will announce its closing. This happened with another prestigious magazine I reviewed in 2008. Shortly after the review went live the magazine announced its closing its print editions and switching to online format only.

Writers work hard. It’s important for us to support each other by not only guiding one another toward the great magazines but also letting each other know what to beware of in the publishing world. If a magazine is a mess of poor editing, it could be a sign that the journal may not have staying power or that it’s simply not right for you. We see one of our roles as helping writers with this process of discernment.

It’s important to hold these journals accountable. I mean, come on. You’re asking writers to take time to send you their work, in some cases demanding a writer’s “best work,” and then not holding up your end of the bargain if you produce something sloppy.

I saw a semi-famous writer post a Facebook status once about subscribing to three literary magazines and “supporting the hell out of them” or something along those lines; e.g., buy the writers’ novels, retweet them, etc. While that’s obviously an amazing idea in theory, I was turned off by the rhetoric of obligation. I’ve noticed a lot of writers talk this way: You MUST subscribe to indie mags, you MUST support indie writers. While I think it’s hypocritical to expect support for your work but not dole any out for others’ work, I also place a lot of value on reading what you love and are naturally drawn to, obligations be damned. How do you walk the line between reading what you love and supporting the scene?

I have two responses here. The first is, the writing world is rich and varied and it needs every one of us. It needs extroverts (who love to go to readings, conferences, book launches, parties, and so on) and it needs its introverts (folks who hate going to or giving readings, people who may not want to be on social media, or would rather stick pins in their eyes than go to some kind of writer party). We need people reading and buying lit mags but we also need people who only want to read Jane Austen or 18th-century crime fiction or who want to live on an island off the coast of some place and just be alone with their words and their ideas. My god, no one should tell any writer how to do anything. It’s hard enough just to fucking write.

My second thought is that I think the idea of what it means to “support” other writers is often grossly simplified. For any significant positive impact to be made on the lives (and livelihoods) of writers, we need to look at the material conditions that shape writers’ lives. Do creative writing adjuncts have health insurance? Are there day-care programs at writing residencies for writer-parents? Are there grants specifically for single parents who write? What can writers do to empower themselves as a class and wean themselves off the big corporations that hold so much power over our lives?

These are the kinds of things that make a difference in an important way. I don’t think subscribing to some lit mags will make or break the writing world (though it’s certainly good for one’s own writing and one’s own career). But working to form a strong writer’s union? Fighting back against the exploitation of adjuncts and grad students? Providing support for working-writer-parents? These things make real difference in the quality of life for most writers, and thus in the quality of their work.

Finally, I have to ask: What are your favorite lit mags? Do you have any sleeper favorites that most people have never heard of?

This is going to sound coy, or dodging-the-question-ish, but the truth is that I cannot compare lit mags anymore. I see them as all so distinct from one another that it’s impossible to say what my favorite is. For instance, how can one compare Granta, which is beautiful, a megastar in the lit mag world, which has its own press and is published by one of the wealthiest women in England to, say, B O D Y, which is this elegant little online lit mag based in the Czech Republic?

There are so many lit mags I love and for so many different reasons: Zoetrope for their design, Hobart for their quirky spunk, Kenyon Review for their sincerity and solidity, Ploughshares for their consistently stellar blog, Overland (an Australian magazine) for their fantastically vocal political views, Beecher’s for their attention to cover design and the feel of the pages, Tin House for their reviews and stories, Creative Nonfiction for their wonderfully teachable content and incredible theme issues, Gargoyle for their inclusiveness, FENCE for their edginess, The Threepenny Review for their old-school style, Paper Darts for the consistently gorgeous artwork, Guernica for their socially conscious themes, Boston Review for their bold political conversations, 100 Word Story for the greatest place to find writing prompts for teens...I could go on. How much time do we have here?

This is the fourth installment of an interview series in which we explore how writing, editing, and publishing are functioning in the Internet age. Our first installment featured successful self-published author Terri Long. Our second installment featured Michael Archer, the editor-in-chief of Guernica magazine. And thirdly, we talked with über-popular romance novelist Gena Showalter about why her genre is stigmatized, and if it matters.

Images: Becky Tuch