Life

Is The Internet Really Controlling Your Mind?

Not to sound like a fringe paranoid conspiracy theorist, but... does anyone else ever feel like they're not entirely in control of how much time they spend online? Particularly on social media sites? OK, stay with me here: Philosophers are now saying that the Internet is programming us , rather than the other way around – and I think they might be right.

Write academics Evan Selinger and Brett Frischmann in a piece in The Guardian titled "Will the Internet of Things Result in Predictable People?":

In order for seamlessly integrated devices to minimise transaction costs, the leash connecting us to the Internet needs to tighten. Sure, the dystopian vision of The Matrix won’t be created. But even though we won’t become human batteries that literally power machines, we’ll still be fueling them as perpetual sources of data that they’re programmed to extract, analyse, share, and act upon. What this means for us is hardly ever examined. We’d better start thinking long and hard about what it means for human beings to lose the ability – practically speaking – to go offline.

The issue is something called "techno-social engineering," which uses technology – for instance the dopamine thrill of someone "liking" a post on Facebook, the terror and anxiety of FOMO, all of those emotions tied in with social media – to modify the behavior of people toward a specific goal.

It's what Facebook did when it showed some users happier posts from their news feed than usual, and some users more negative posts than usual, in order to see if this could influence users' emotions – and as it turned out, it did, though just slightly. It's how games like Candy Crush keep you playing (and buying upgrades). It's also what Facebook did when it used graphics and digital "I voted" stickers to encourage users to vote – something that had a significantly more prominent effect. (Imagine if Mark Zuckerberg only encouraged people with the same political views as him to vote in this way.)

This influence may only get larger as we spend more and more time with technology. We already carry around computers in the form of smartphones, and increasingly we carry smartwatches as well. Selinger and Frischmann even talk about a techies longing for a future when the walls in our houses communicate our children's moods to us – a time in which there really would be no escape from being recorded and observed by the Internet. Worse, this all is painted as desirable – and, no doubt, it would be pleasurable, in a way.

There is a reason I keep going on social media, after all. The sites are programmed to be addicting – increasingly so. Engineers find ways to increase the length of time people spend on each page in order to make more advertising money; they find ways to keep us online for longer and longer hours; we lose time to other kinds of work and socializing and get our fix through the Internet instead as a kind of half-replacement, like taking morphine instead of heroin. We need more of this similar thing to achieve the same kind of fix.

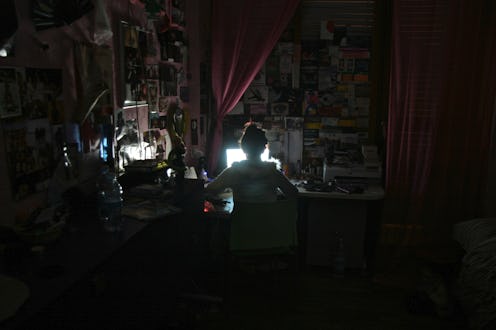

It's pathetic, but can I just tell you right here about the nights I've stayed up late scrolling through Tumblr as an approximation for reading, or stalking other people's successes on Facebook as a way to avoid thinking about my own projects? I even use Pinterest obsessively, pinning clothes I want to buy to capture some of the dopamine I'd feel if I could walk into a store and buy it. (Is there any wonder that Millennials, an incredibly disadvantaged generation economically, are the least resistant to the mostly cost-free joys of the web?) When I've told friends this, the advice has been: just stop using it. They usually say this while double-tapping something on Instagram.

But going off of social media comes at a huge cost – increasingly, people my age use it as their primary form of communication. I'd miss out on career visibility and party invites and miscellaneous real world opportunities by leaving something like Facebook entirely. People get jobs from Twitter, for goodness' sake. It's not like this is a thing without any real value, and even if I could change, the world wouldn't – after all, even mass preferences and ideas about privacy and the value of the internet are being changed by companies who benefit from increased online use and engagement. Says the Guardian article:

Our willingness to volunteer information, even for what we perceive to be for our own benefit, is contingent and can be engineered. Over a decade ago, Facebook aimed to shape our privacy preferences, and as we’ve seen, the company has been incredibly successful. We’ve become active participants, often for fleeting and superficial bits of attention that satiate our craving to be meaningful. And Facebook is just the tip of the iceberg.

It's the end of the article that's most frightening, though:

Alan Turing wondered if machines could be human-like, and recently that topic’s been getting a lot of attention. But perhaps a more important question is a reverse Turing test: can humans become machine-like and pervasively programmable.

Just... think about that for a moment.

Images: Alessandro Valli, Johan Larsson, Garry Knight, Federico Morando/Flickr