Life

The Science Of Ouija Boards Is Straight Up Eerie

Usually when science debunks supernatural theories, it saps all of the fun (and the scariness) out of things. However, the scientific explanation for how Ouija boards work is almost as creepy as the idea the boards tap into the occult. Studies in the last few years have shown that, rather then fostering communication with the dead, Ouija boards work by extracting knowledge that we may not even be aware that we have. When playing the game, our bodies move without our knowing, spelling out ideas of which we are unconscious, but that are nevertheless housed in our brains. In other words, THERE IS SOMETHING INSIDE US COMMUNICATING THAT WE DO NOT EVEN KNOW IS THERE. Please excuse me while I have a fit of the vapors.

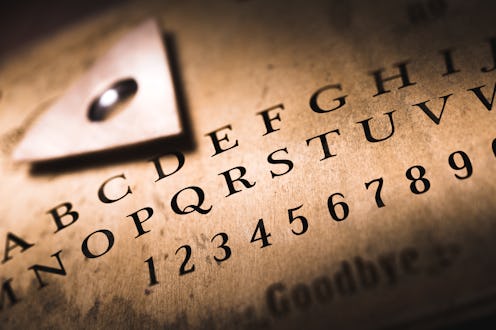

You may be most familiar with Ouija boards from your days of middle school sleepovers, when using a board game to talk to the dead, playing “Light as a feather, stiff as a board,” and freezing the bra of the first person who fell asleep were normal features of adolescent bonding. The Ouija board, however, has actually been around since the late 19th century, when spiritualism, based upon a belief in the potential of communication between the living and the dead, became popular in the United States, England, and Europe. The Ouija board hasn’t changed much since then; it features the letters of the alphabet, the numbers 1 through 9, the words “yes” and “no” in the corners, and “Goodbye” across the bottom. Players divine answers to questions using a tear-dropped shaped planchette that slides across the board.

The way that people use the Ouija board is affected by the ideomotor effect, a psychological phenomenon wherein people move without intending to, and without being conscious that they are moving. Thus, when using a Ouija board, a player might honestly think that he or she is doing nothing to move the planchette, even when he or she is actually directing its motion.

A study conducted in 2012 at the University of British Columbia investigated how the ideomotor effect could betray unconscious knowledge. In the study, subjects were asked a number of questions verbally. They were then put in front of a Ouija board, blindfolded, and told that they would be answering questions by touching the planchette with a partner. The partner would then leave quietly, and the subject would answer the questions using the Ouija board alone — all the while thinking that there was another person touching the planchette, and assuming that they weren’t in control of the board. The study found that subjects answered more questions correctly using the Ouija board than when answering verbally, suggesting that their unconscious movements reflected unconscious knowledge.

Research from 2014 found similar results. In this study, also conducted at the University of British Columbia, psychology researcher Docky Duncan had subjects answer a series of “yes” or “no” questions using a Ouija board while blindfolded. He found that most subjects correctly answered two thirds of the questions — even when they didn’t consciously know the answers. Duncan explained to CBC,

Ask someone if they know, you know, 'What's the capital of Cambodia?' and they might say, 'I have no idea.' But they might have heard it somewhere, and it may actually be inside your brain somewhere. … When we ask people these questions using these unconscious answers, suddenly players can actually access that knowledge and it really becomes manifested.

This explanation for how Ouija boards work might not be as otherworldly as “speaking to the spirits of the dead,” but it suggests the hair-raising possibility that we know things that we don’t know we know — and that our bodies are able to act on that knowledge without our consent. And that's plenty creepy all on its own.

Images: fergregory/Fotolia; Giphy