News

The One Reason This Veto Is So Controversial

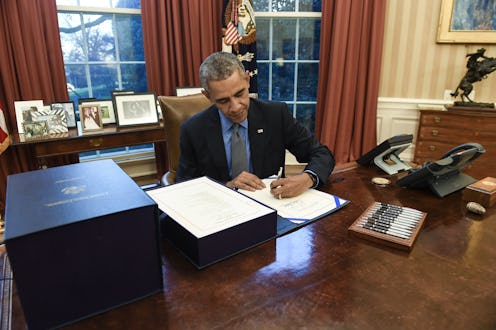

President Obama used a controversial pocket-and-return veto on Friday to keep a key climate change bill alive in Congress. The Republican-controlled Congress was attempting to pass a resolution that would have rescinded emissions regulations on power plants, and Obama refused to sign the bill and returned it to the Senate with a veto message. But Obama's clear intention doesn't mean the veto will hold up in court.

The Clean Power Plan is part of Obama's climate change initiative, which promises to reduce emissions by 32 percent in 2030. The plan was a huge factor of the negotiations at last month's United Nations Climate Conference in Paris, and Obama's recent commitment to addressing climate change means his support of the bill is no surprise. Yet, energy lobbyists and the Republican party are fighting to keep those measures from becoming law by introducing the two resolutions that Obama vetoed, and fighting against the regulations already in place.

Pocket-and-return vetoes are a hybrid of two types of veto against a bill the president does not support. A return veto happens when the president returns a bill to Congress with a message stating his objections to the legislation. For the pocket veto, the president simply does not sign the bill into law after Congress has adjourned, and after 10 days, the bill dies. Obama, like some of his modern predecessors, has favored the combination of the two — not signing the bill, and returning it to the Congress with a veto message.

But there have been grumblings from Constitutional scholars in recent years about the legality of the practice. "The Constitution gives the president two opposing choices. One is the pocket veto, the other is the regular veto. It offers no provision for combining the two somehow. It's a perfectly ludicrous proposition," said constitutional scholar Robert Spitzer after President Obama's pocket-and-return veto on a labor regulations bill in April. The practice isn't expressly condoned in the Constitution, so academics are concerned that it isn't truly legal.

The scholarly disagreement about the pocket-and-return veto process means the EPA regulations may be more susceptible now to legal action in the courts. Twenty-four states are already challenging the new regulations, and the constitutionally disputed vetoes may not help keep the regulations in place. West Virginia Attorney General Patrick, who is leading the fight against the regulations, called the new emission restrictions "a blatant and unprecedented attack on coal."

Obama's use of the pocket-and-return veto has yet to face any serious credibility threat, but the more he uses them, the more attention is brings to the constitutional ambiguity of the situation. Although the president is allowed to veto any bill of his choosing, the combination of the pocket veto and return veto is becoming more controversial as it becomes more frequently used. But the new court challenges could mean a definitive affirmation or denouncement of the legality of the pocket-and-return veto soon, clearing up any remaining questions of its legal standing.