Books

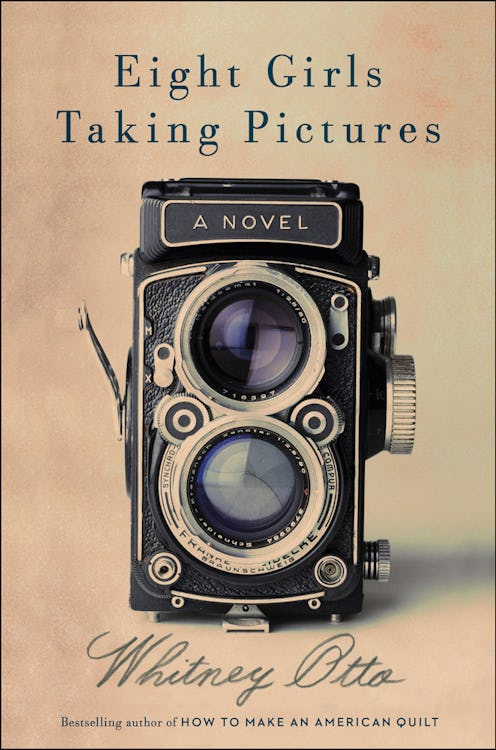

Exploring Femininity in 'Eight Girls Taking Pictures'

Whitney Otto’s sweeping, historical novel, Eight Girls Taking Pictures (Scribner), offers a tantalizing glimpse at the lives of eight female photographers. The stories of these fascinating women span the tumultuous 20th century, covering two world wars and the wild suffragette movement. Though nearly all of the artists portrayed in this novel come from progressive-minded, financially well-off families, each woman goes through her own unique struggle with new, protean conceptions of femininity.

The fascinating female characters that come to life in Eight Girls Taking Pictures come together to present eight different—but often overlapping—reflections on gender. A snapshot of each:

1. The suffragettes: In early 20th century London, feminism took the form of the “suffragette” movement, which advocated for giving women the right to vote. But when rallies and pamphlet distributions yielded unsatisfactory results, the suffragettes resorted to more ferocious tactics to achieve their goals. This evolving modus operandi alienated young women such as Amadora Allesbury, who believes wholeheartedly in equal rights for women but shies away from the suffragettes’ “campaign of violence.” Elucidating her decision to disassociate with the movement, Amadora explains the black-and-white nature of the evolving suffragette movement: “If you signed on, you signed on for the lot.”

2. The moderate feminists: Amadora is told that she is “too well-adjusted, too happy and attractive” to be a suffragette. This blunt categorization reflects the tension that is inherent in any non-extremist movement: an alleged lack of total commitment to The Cause. Jessie Berlin, a photographer whose story is detailed later in the novel, expresses her frustration with the ‘70s-era feminism movements in very similar terms. She notes that the stark, uncompromising, capital-F feminism that her friends embrace is at odds with her personal experiences—that she doesn’t, for example, hate all men—and prevents her from adopting the movement altogether. Instead, she embraces a moderate form of feminism that allows for more picking and choosing.

3. Woman as a role-player: Though Otto’s characters are generally unsatisfied with the radical evolution of feminism in their times, the other extreme proves to be equally unpalatable to them. Renaissance-era artists famously touted the mutability of man, but a woman’s role has always been viewed as fixed and unmovable. Yet, even the modern “mutable woman” is still confined; Charlotte Blum and her posse of intellectually enlightened friends lament the image of woman as a “role-player” because, far from liberating her, it places her in a specific category. For her own part, Charlotte despises the lack of fluidity between categories of women; she doesn’t hate being a wife the way many of her contemporaries do, but she is frustrated by her inability to be “wife, mother, lover and photographer all at once.” The intersection of these roles, Charlotte explains, presents an “unsolvable equation” that, for men, is not even a problem in the first place.

4. Woman as anything other than herself: A corollary of the idea of woman as a role player is the notion that she can never simply be herself. This is reflected in the lives of nearly every character in the novel, as each woman struggles with finding her own identity outside of society’s expectations. Charlotte, especially, grapples with this issue. She’s fired for designing a mannequin display that is deemed to be “an act of rebellion”—but just as a cigar really is sometimes just a cigar, Charlotte means for her mannequin display to signify nothing more than just itself.

5. Androgyny and liberation: Freedom is one of those tricky terms that can be viewed both positively and negatively. Freedom from societal constraints is a positive ideal, but freedom from purpose can be paralyzing and confusing. Ellen Van Pelt, a nude model who was often photographed (quite sketchily) by her father, went by the gender-neutral nickname “Lenny” and dressed and acted like a tomboy. But her lack of an assertive identity left room for others to construct an identity for her. She was viewed as bold, beautiful, and the ever-vague “modern,” but always as an object, and never as a subject. Jenny Lux, however, was raised not as if she were a boy, but just the same as a boy. Jenny's total abstention from social conventions was more confusing than liberating—both for her and the people around her.

6. Woman and her ‘hobbies’: Many of these women, despite the progressive culture surrounding them, were unable to completely break free from the “housewife” mold. Cymbeline Kelley falls in love with Leroy precisely because their artistic visions are in perfect alignment—but several years later, he is the one traveling for months on end to pursue his art, while she remains tied to her domestic responsibilities in the home. This confinement is represented by Cymbeline’s photographs of her garden, and, later on, Miri Marx’s pictures of the view from her bedroom window. Miri notes that if a woman splits her time between her work and her children, she is viewed as “neglectful,” but her male counterpart could “be as absentee as [he] liked.” For this reason, anything a woman chooses to do outside of her True Profession—that is, raising the kids—is often viewed as, at best, a mere hobby.

7. Feminine art: A novel about female photography will inevitably explore the idea of feminine versus masculine art, and Otto does so delicately and beautifully. Amadora believes that women are uniquely tailored to be “masters of color” due to their tendency to get creative with different hues of makeup, jewelry, and other types of adornment. She also maintains that women are better portraitists than men are, because although men tend to get caught up in their own prowess as artists, the female tendency is to focus more on the actual model. These categorizations are, in themselves, neither praising nor damning, but Amadora learns a slightly more sinister lesson about the differences between male and female artists from her mentor, Lallie Charles.

8. Woman as "ladylike": The term “ladylike” itself suggests a decidedly delicate manner of thinking, speaking, and acting. Famed London photographer Lallie Charles epitomizes this performance with her “illusion of effortless ease.” Amadora notes that this is the most important lesson she learns from Ms. Charles—no one likes to see a woman sweating it out, because hard work is decidedly unladylike.

By the conclusion of this delightfully twisted gender study, you'll be wondering what it is to be feminine after all.

Image: Grete Stern's 'Electrical Appliances for the Home' from LesGouExposiciones.