News

Non-Binding Primaries Are Undercutting Sanders

On Tuesday, Washington held its Republican presidential primary, and the outcome was exactly what you'd expect with only one candidate left in the race: a big win for Donald Trump en route to his official coronation at the Republican National Convention in July. But there was a contest on the other party too, albeit an unusual one. Washington also had a non-binding Democratic primary. And based on the results, a certain Vermont senator might be feeling some angst. The non-binding primaries are really hurting Bernie Sanders and his claims of "political revolution."

To be clear, Hillary Clinton's primary win on Tuesday had no impact on the Democratic race whatsoever. Sanders still trails Clinton by hundreds of pledged delegates, but his deficit didn't widen at all, because you don't get delegates for winning a non-binding primary. Washington holds caucuses to award delegates, and that was settled on March 26. Sanders won, and by a staggering margin ― he beat Clinton by about 45 points, securing 74 of the state's 101 delegates.

But on Tuesday, when Washington voters headed to the polls to vote in their effectively symbolic primary ― which saw hundreds of thousands more Democrats turn out than for the caucus ― the result was altogether different. Clinton beat Sanders by eight points, dealing a heavy blow to his late-campaign mojo, all without winning a single delegate.

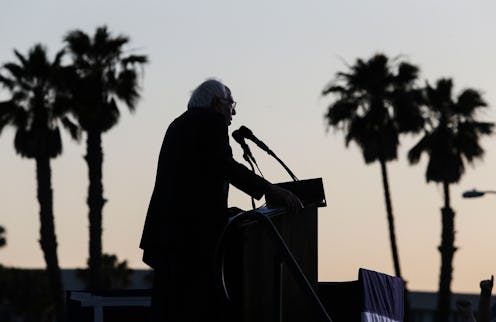

Throughout his campaign, Sanders has effectively pitched himself to Democratic voters as an authentic, humble, and tireless public servant, with has a political vision of basic fairness and economic equality that could transform American politics. And all of that may well be true, with the possible exception of the "humble" part. How long can you really stay humble with crowds like these, after all?

But above all else, Sanders has presented himself as the progressive voice that the Democratic base is really clamoring for: an antidote to the cynicism of establishment politics, and the kind of politician whom people actually want to vote for, rather than feel forced to support. Which is where the non-binding primaries come in ― in addition to Washington, Nebraska held one earlier this month, and it brought the same outcome. Clinton won again, this time by 19 points, turning around her 14-point loss in the Cornhusker State's caucuses in March for a total swing of 33 points.

What these numbers mean, in simple terms, is that as more of those states' Democratic voters actually went to the polls, the better Clinton ended up doing. This stands in stark contrast to a whole lot of Sanders' rhetoric about his candidacy. He regularly talks up his need for high voter turnout, but perhaps the most dominant performances of his candidacy have in caucus states, where turnout is necessarily, predictably lower than it could be through a simple primary.

Caucuses are, it must be said, less democratic than traditional primaries, because they force people to set aside hours of time to participate, and to vocally support the candidate of their choosing in a public (and potentially contentious) setting.

You can easily imagine countless voters simply being unable or unwilling to participate under these circumstances. It may not sound like much to somebody who's young, especially politically outspoken, or has a lot of free time. But when you consider people with restrictive work schedules, family responsibilities, or hey, even people who might feel too socially awkward to participate in that kind of communal event, it's pretty easy to gather why caucuses don't draw nearly as many people as primaries. Both in outcome and design, they're far less inclusive than the alternative. At the very least, if you're opposed to closed primaries (like Sanders and many of his supporters are), then you should also be opposed to caucuses having any place in the process.

When Sanders has been challenged on how he'd actually implement his legislative agenda ― which includes a $15 federal minimum wage, the breaking up of Wall Street megabanks, and the reversal of the Supreme Court's Citizens United ruling, among other things the Republican Party will definitely not play ball on ― he's suggested that it'll take millions of Americans rising up behind him. And that does ring true; if there's a way to induce a Republican-led Congress to do those things besides overwhelming popular mandate, I sure can't think of it. And it dovetails perfectly with Sanders' core political brand of teeming populist energy.

But what happened in Washington and Nebraska ― as well as the fact that he's still losing the race by virtually insurmountable margins, even with all those caucus states ― serves as a stark reminder that Sanders' ideas haven't propelled him to the top of the party. And even his current successes may be overstated by the existence of the caucus states. It's not implausible (in fact, it's very plausible) that if the more democratic primary system were used everywhere, then he'd be performing considerably worse. None of this is an indictment of the man or the worth of his ideas, obviously. But it does cast the feasibility and credibility of his revolutionary claims in an increasingly dim light.