News

Who I Thought Of When I Heard SCOTUS' Ruling

As an immigration attorney who works on getting people released from detention centers, it was a pretty typical Thursday for me. I was sitting in immigration court at the Elizabeth Detention Center in New Jersey, getting ready for a hearing for a young man who’s in detention, and I was actually feeling kind of hopeful. I was in a good mood, because I’d seen the positive decision that the Supreme Court had made upholding Affirmative Action that morning. I was hoping that perhaps the court would also swing that way in favor of the immigration reforms that the Obama Administration has proposed, DACA and DAPA. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA) allows immigrants who came to the U.S. as children to apply for temporary protection from deportation and work permits, while the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans program (DAPA) allows immigrants who have U.S. citizen or permanent resident children apply for deportation protection and work permits.

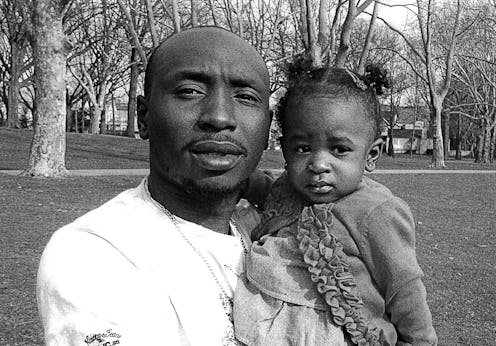

When I saw, minutes later, that the Supreme Court had all but killed DAPA and DACA in a 4-4 deadlock decision, it wasn't just that my heart sank. I immediately felt slightly panicked, because one of my clients, Moussa, is currently sitting in a detention center in Louisiana. Immigration enforcement has already tried to put Moussa on a plane to his home country of Chad once before. I requested that they stop his deportation, in part because he’s eligible for DAPA. I had been really, really hopeful about this decision going positively, because I was confident that if it did, I could probably get him out of detention almost immediately and on his way back home to New Jersey, where he belongs, with his family. Moussa has five children — three biological children and two step-children — all of whom are minors and U.S. citizens. His wife is also a U.S. citizen.

Right after I found out about the Supreme Court's decision and returned to my office, Moussa's youngest son, and his wife, Victoria, were waiting for me. I hardly ever get to see Victoria. She’s very busy. It’s very difficult to get in touch with her — she’s very overwhelmed as the sole caretaker of five children, all under age 10. But I had specifically asked her to come to my office to give me $155 to file what’s called a "Stay Of Removal" for Moussa, which is basically telling Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “please exercise your discretion in this case, because this person is not a threat to national security, they’re not of federal interest, they’re not a priority for enforcement of removal, and they have all these really strong ties to the U.S., so you should allow them to stay.”

It was heartbreaking to see Victoria and her youngest son, who is named after Moussa, and to have to tell her the news about DAPA. Victoria is under an enormous amount of stress, and she and her children are in somewhat deep denial that Moussa might actually not come home.

Victoria kept saying, “Oh, when he gets home he’s gonna be so upset that it took me so long to get you this money order.” It was heartbreaking to see his little boy, the one child who’s named after him, who is very sweet and looks just like him. He doesn’t talk very much; he mostly looked down at his toy truck, but he kept mumbling, “Oh, daddy’s coming home.”

You can sign the Change.org petition for Moussa's release here.

Victoria keeps hoping that everything is going to work out, and I don’t think she understands how someone with an entire U.S. citizen family would just be deported. I think she just keeps thinking that this is some sort of colossal joke or nightmare. I don’t think she understands. Moussa is the perfect candidate for DAPA. He’s exactly the kind of person that this program is meant to assist, but now, with the proposal all but killed, I’ve just lost one of my strongest factors in his case. The reality is — now especially — that he might not come home. It’s a very strong possibility, in fact.

The first thing I noticed when I met Moussa, before he was even my client, is that he is someone who cares about others, because he volunteered with the organization I work for, American Friends Service Committee. In his home country, Moussa was a computer engineer. He entered the United States with a valid visa as a student in 2007, and when he found out that he could perhaps have asylum here in the United States, he applied for it. Moussa's claim was that he endured torture by government officials after he witnessed a murder in Chad.

Though he was a law-abiding, productive contributor to society, Moussa lost his case for asylum. It doesn't mean what he claims isn't true; there are many ways you can lose an asylum case. It can be you don’t file on time — you have to file for asylum within one year of coming here — or it can be you have a criminal conviction that doesn’t allow you to get asylum. Or the immigration judge can just decide that they don’t believe you. Perhaps on the statement that you submit, you said, “four guys beat me up,” and then when you testify you might say, “three guys beat me up.” If you have enough of these inconsistencies, the judge can make a determination that they don’t find you credible, and that’s what happened in Moussa’s case. Sadly, a lot of people who are survivors of violence and torture have trouble recalling facts, dates, numbers. I don’t know who was representing Moussa at that time; I just know that after he lost that case, he filed for an appeal.

It takes some time to get to a judge, and by the time he did, he had already begun dating his wife, Victoria. His deportation order didn’t become final until 2011, and by then, they already had a child together. Even though Victoria is a U.S. citizen, he’d been ordered deported, so he couldn't get a Green Card based on their marriage, though he tried applying for one anyway.

Moussa was his family's financial provider. He had a partner in a small business, and he paid taxes the entire time he’s lived here. All 9 years, he’s paid taxes. Now, American taxpayers are paying over $100 a day for him to be in a detention facility, and for his wife to be on welfare, instead.

Moussa didn’t leave because he was afraid of what would happen to him if he were to return to Chad, and because he’d already had a child here, a family that depended on him. After Moussa applied for a Green Card, Immigration Enforcement was immediately notified and they picked him up just outside of his home and put him in Immigration Detention — the very one that I was sitting in when I found out about the Supreme Court's ruling Thursday morning.

That was 10 months ago. Since then, Moussa's been transferred to detention in Louisiana, and his wife had to go on welfare, because there is no way she can provide for five children under 10 years old and also afford childcare. Moussa was his family's financial provider; he had a partner in a small business, and he paid taxes the entire time he's lived here. All nine years, he’s paid taxes. Now, American taxpayers are paying over $100 a day for him to be in a detention facility, and for his wife to be on welfare, instead.

There are over 250 facilities in this country that are used to detain non-citizens or immigrants when they’re in deportation hearings. There’s also a whole other group of facilities for people who are being prosecuted for illegal reentry, and they are very frightening. They’re called "shadow prisons," and they have horrifying conditions, as the ACLU's investigation into them (among others) has substantiated. But even the "nicest" detention center is still modeled after jails, and a lot of places where immigrants are held are actual jails. They’re county jails that have contracts with the federal government to hold people while they’re awaiting their case. That's where Moussa is sitting, and waiting, right now. It's where he's been sitting, and waiting, for 10 months now.

But if the Supreme Court had decided that DAPA could be rolled out, I could have immediately applied for him not to be deported. And, since Moussa’s not a danger to the community at all — since he’s only in detention in order to effect his deportation — he could have been on his way home. If they had decided that DAPA should be rolled out, I’m very confident that Moussa could’ve been with his family by the end of the week.

Luckily, what just happened isn’t necessarily the end of Moussa's case. I’m still going to use that money order, and I’m going to make an even stronger request. I’m not going to throw out the fact that he’s eligible for DAPA, because DAPA is not dead yet. It’s going to continue. They’re fighting it out in the lower courts, and that’s going to take some time. Much of the outcome may depend on who gets elected; Hillary Clinton has promised that not only would she support rolling out DAPA, but that she would potentially expand it to reach more people. Trump adamantly said he would throw DAPA out.

Moussa entered the U.S. with a valid visa and he took legal steps to seek asylum here. Our laws treat people who come here to seek asylum as if they are committing a crime when, in fact, they are refugees. Every person who lives here in the United States and contributes to our communities, to our economy, to our families, deserves a path to citizenship.

My job can be very exhausting and emotionally taxing. But for all the sad things that I experience and the sense of helplessness that’s sometimes overwhelming, when I do win someone's freedom from detention or prevent their deportation to somewhere that would mean their death, it makes up for all those other days that I feel overwhelmed. It makes it worthwhile. Even though the odds are now more stacked against him, I hope that soon, Moussa will be one of those victories.

You can sign the Change.org petition for his release here.

As Told To: Rachel Krantz

Images Courtesy of Moussa's family.