Life

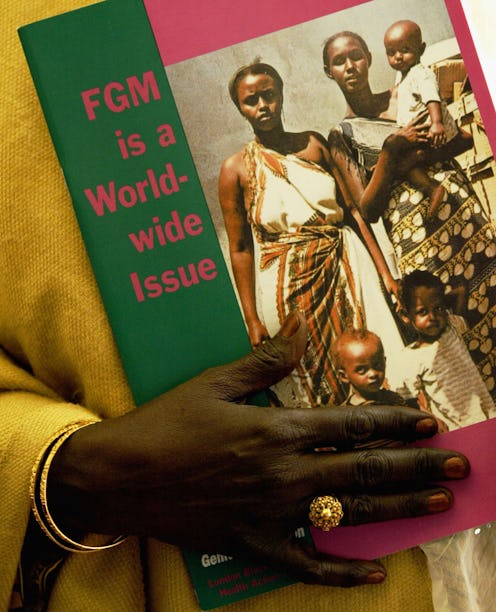

6 Things Everyone Should Know About FGM

If you’ve never heard of female genital mutilation, or FGM, you’ve saved yourself a lot of empathetic agony; the details are upsetting, particularly for the weak of stomach or any possessor of female genitalia. But you should know about it, because it’s both upsettingly common and extremely traumatic and dangerous. FGM is done to young girls, infants, and teenagers in a range of countries across the world for varying reasons and as part of several cultural contexts, but the basics are clear: it involves somebody physically damaging female genitalia in a ritual way that’s designed to remove sexual pleasure and seriously impede the natural functioning of a healthy female body.

Interestingly (and alarmingly), the practice is so widespread and proving so tricky to eradicate that a recent proposal to an academic journal proposed “compromising” and giving girls’ genitals a ritual “nick” under anesthetic instead of more brutal forms of mutilation. The suggestion met with an outcry among medical professionals and activists alike, but it’s a sign of how bad things are when principled medical thinkers are genuinely suggesting “only doing a little bit” of mutilation.

Here are six facts to know about FGM, including how it varies, where it happens, and what you can do to stop it.

1. It’s Widespread — And It Happens In America, Too

The latest figures, released by UNICEF in February 2016, indicate that over 200 million girls and women worldwide have undergone FGM, a number that includes a previously-uncounted 70 million in Indonesia. The practice is largely concentrated in Africa, but also occurs in other nations worldwide and among some migrant communities. Egypt, Guinea, and Dijbouti are world “leaders” in the practice, with over 90 percent of their female population between the ages of 15 and 49 thought to have undergone it. It also shows up in Iraq, Yemen, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and other Middle Eastern and Asian countries, even though some have express laws forbidding it. A study by the CDC has also found that the number of girls at risk of FGM in the United States has tripled in the past 25 years; so this isn't just an issue that happens in faraway places.

2. It’s Designed To Ensure Female “Chastity" & “Cleanliness”

FGM is a cultural practice carried out on girls at a variety of ages, from infancy to five or six years old and up to the teenage years; but whatever age, it’s a part of a tradition based on limiting female sexuality and controlling chastity before marriage by taking away the possibility of a woman’s clitoral sexual pleasure. The activist Ayaan Hirst Ali, who underwent FGM at the age of five, has called it part of the “whole virginity obsession;" in some FGM cases, the mutilation makes it clear if anything else has “entered” the vulva before the girl’s wedding night. It’s often seen as a rite of womanhood; Daughters Of Eve, an anti-FGM activist organization, explains that it forms the basis of various initiation ceremonies, can be a condition of marriage, and is dictated by the belief that “women will be unhealthy or unclean or unworthy if they don't have FGM”.

3. There Are 4 Main Types Of FGM

FGM is actually divided, upsettingly enough, into four “types,” and the type that’s administered depends on cultural tradition and geographic area. According to the charity Forward, type 1 means a complete or partial removal of the clitoris, type 2 means a removal of both the clitoris and the labia minora, type 3 means narrowing the opening of the vulva through surgical sewing of the labia, and type 4 is any other kind of interference with the genitals for non-surgical purposes, including scraping, pricking, or piercing any part of it. The types aren’t completely distinct, though; types 2 and 3 in particular can contain other elements or variations.

The instruments also differ widely; surgical scalpels, glass, blades, or any kind of sharp ritual instrument can be used, sometimes on several girls at once without proper sterilization, which is one of the reasons it’s such a highly dangerous procedure.

4. Medical Professionals Can Be Complicit In It

While many cases of FGM are performed by family members or ritual elders, the practice can also take place in a pseudo-medical setting, which is, if anything, even more frightening. The UNFPA’s studies on this “medicalization” of FGM indicate that as many as one in five girls who’ve suffered from FGM have had it done by a doctor or in a hospital, even if the procedure’s highly illegal — 77 percent of Egypt’s FGM cases are thought to have been done by a doctor.

One of the really alarming things about this is that, according to doctors Pierre Foldes and Frederique Martz, who've performed reconstructive surgery on victims of both medical and “at-home” FGM procedures, the medical ones usually cause much more damage and are harder to help. “Traditional cutters,” they explain, “are very well aware of how far they can go, particularly in terms of bleeding, and they understand that the death of young girls will neither serve their reputation nor help with recruiting new clients.” A doctor, however, isn’t so worried about blood loss because they know how to stem it, and can do a lot more damage when the patient’s anesthetized.

A 17-year-old girl died in Egypt in early 2016 while undergoing an FGM procedure in a hospital, and another died a year earlier. Having a medically supervised FGM may reduce the risk of infection and other possibilities, but it’s still nowhere near safe or ethical.

5. It’s Deeply Dangerous And Traumatizing

It’s important to emphasize this: there aren’t any health benefits of FGM. It doesn’t make women more fertile, which is one of the folk beliefs about the practice, and it certainly won’t help sexual pleasure after a woman is married. But serious sexual difficulties are not the only problem girls and women experience post-FGM. The World Health Organization’s litany of potential complications is startling and upsetting: women can suffer both short- and long-term medical harm from the procedure, ranging from serious agony to nerve damage, menstrual difficulties, an increased risk of HIV, the possibility of difficulty giving birth, infections in the genitals and abdomen, and death; and that’s not even counting the psychological toll.

Type 3 is regarded as the most harmful of all the FGM types; the UNFPA explains that women who’ve suffered being sewn up often have to be “cut open” on their wedding night by their husbands to allow sex, and then possibly cut again at childbirth to allow for the baby to pass through the birth canal. The associated risks of tetanus, shock, blood loss, infection, and death are substantial.

6. You Can Take Action To Help Stop It

Stopping FGM is going to be incredibly difficult; the lure of tradition, religious sanction, familial approval, and community acceptance is a strong one. An ex-cutter explained to PLAN International that the practice was “lucrative” and “at a community level practitioners are considered to have spiritual powers that makes them strong in the community, and they are respected by both men and women.” That sort of power is hard to give up, but it’s one of the things that’s targeted by NGOs working to root out the process through educating communities about its dangers.

If you want to help, the best options are often volunteering or donating to organizations that specialize in FGM and its eradication, like Daughters of Eve or Forward. Get involved in social media campaigns and pressure groups, and if you have serious evidence that anybody is at risk of the practice in your community, talk about it; the NSPCC has a guide to how you might be able to detect signs that a child is at risk.