Life

Where Is Michael Johnson Now?

As someone who was once billed as "the fastest man in the world," Michael Johnson's legacy is pretty uncontested: he's one of the greatest sprinters of all time, period. Kitted out with personalized Nike gold shoes in two different sizes to accommodate his slightly different feet, Johnson dominated the 200m and 400m in the 1990s; his 400m time remains both the world and Olympic record, while his 200m time stood for over a decade before Usain Bolt (of course) broke it. He's still tied with Carl Lewis for the most gold medals won by a runner.

But what's Johnson been doing ever since? As it turns out, his period since his official running career ended has been both occasionally tumultuous and consistently busy. If you're just looking for a brief recap of native Texan Johnson's achievements, you may be disappointed — because there's simply too much to fit in. But don't worry; his life story is interesting enough to take the extra minute or two to read through.

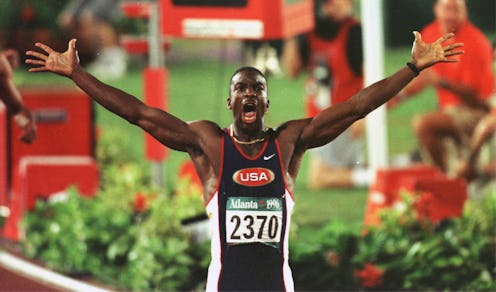

"The greatest 400-metre runner of all time," as the Telegraph referred to him in 2014, didn't come from wealth; he recalled in 2014 that his first job, in 1985, was "working for Toys R Us in the Christmas break.... we got about $3 an hour in 1985, and I would get home at 1.30am." (He's since been very frank about the financial side of athletics, saying that gold medals are realistically a way to attract substantial endorsement deals, rather than a paying dividend on their own.) His finest moment was likely at the Atlanta Olympics in 1996, where he became the only man in history to win both the 200m and 400m at the same event. But he was both the indoor and outdoor champion over both distances, winning eight World Championship golds over his career and five Olympic golds — though he'd later hand one of those medals back (more on that later). He was elected to the National Track & Field Hall Of Fame in 2003, unsurprisingly.

Since then, though, Johnson has diversified. As an athletics fan residing in Britain, I've witnessed one of his highest-profile jobs: one of the head athletics commentators for the BBC for international championships. "As a commentator," he told the Guardian in 2014," I think I have ability but I've had to work hard at it. I've never modelled myself on anyone. But watching sport, there have been plenty of commentators I've found annoying. If anything, I've modelled myself on not being like them." He's out in Rio in the BBC commentary box once again, but his commentating peak may have been hit in 2012, when he and his other commentating experts, Colin Jackson and Denise Lewis, went absolutely bonkers as British runner Mo Farah won the 10k Olympic gold.

Johnson's own particular experience has made him a vocal (and at times brutal) critic of the state of doping in modern athletics. In 2008, he voluntarily handed back the 4x400m relay gold he won at the 2000 Sydney Olympics after it was revealed that fellow relay team member Antonio Pettigrew had been doping at the time. “I was very angry and disappointed," he told a journalist in 2012. "For eight years I could say I was a five-time Olympic gold medallist. Then I had to start saying four-time. It doesn’t sound the same. Now I’m more sad than angry. The stupid thing is it was so completely and totally unnecessary."

With worldwide conversation about doping in athletics reaching a fever pitch — Russia, for instance, has just been banned from any participation in the Paralympics in 2016, thanks to a damning report about systemic governmental fiddling with athletic urine samples — Johnson's been at the forefront of the discussion.

And he's had a consistent position: that it's structural failure, not individual weakness, that's the real issue with doping athletes. In 2015, he told athletic website Sport360, “Athletics has done a good job having a zero tolerance policy towards doping and has led over the years with regards policy towards doping. The issue, though, is when the conversation moves from being less about who may or may not be doping to whether or not the organization trusted with protecting those clean athletes and policing the sport is doing its job properly."

And when the International Association of Athletics Federation was plunged into crisis in early 2016, with three senior officials (including then-President) banned for breaching doping rules, Johnson told the BBC that the IAAF should be completely torn down and rebuilt from scratch. "It is the governing body — and the very structure of the governing body — that has allowed this type of corruption," he said.

Aside from this kind of spotlight-grabbing perspective, Johnson's also using his powers for good. He's the founder of Michael Johnson Performance (MJP), one of the most high-end training facilities worldwide (with more than a few of its stable competing in Rio 2016). He also works for soccer team Arsenal as an athletics development expert, and in 2016 announced the debut of his global charity Positive Track, which brings young community leaders to the MJP facilities to learn how to use sports to help community development and social change.

But he hasn't stayed out of the headlines: he dropped out of The Celebrity Apprentice after five episodes in 2010, and in 2012, he helmed a documentary for UK's Channel 4, Survival Of The Fastest , that aimed to answer a question: "if African American and Caribbean athletes are successful as a result of slavery." The program's controversial conclusion? The extraordinary hardships of the slave trade may have meant that exceptional athletes were more likely to survive, honing their descendants into Olympic medal winners.

Overall, don't expect Johnson to slow down or disappear. Though the gold shoes may have been hung up, he's still charging forward in athletics and beyond.