Life

7 Historic Feminist Olympic Moments

We're now fully into the Olympic Games in Rio, and, alongside the stupendous feats of athleticism being displayed by people from around the world, there have already been some pretty outrageous incidents of sexism in Olympic media coverage. An NBC sportscaster came in for massive criticism after he said the husband and trainer of Katinka Hosszu, the gold-winning Hungarian swimmer, was "responsible" for her win; BBC sports presenter Helen Skelton was barraged with criticism for daring to show her legs in shorts while reporting on swimming; and the Chicago Tribune got justly lambasted for referring to medallist Corey Cogdell-Unrein as the "wife of a Bears lineman" instead of by her name. Clearly there's still a long way to go in the world's treatment of women around and in sports; but the Olympics in particular has had a fairly remarkable journey in its involvement with female athletes. So what moments in feminist olympic history would remind us of the progress we've made?

Much of societal change is taken in small increments rather than big leaps, and the Olympics is a definite example of that; from the first 22 female athletes at the 1900 Games, the percentage of female participation in the Games has climbed every year. In 1992 they made up a mere 28.8 percent of the total athletes, but in 2016 they're at 45 percent. Included in that increase are many small victories, from the first African American female participants to the groundbreaking figures who made giant moves for their country or discipline. Everybody loves a good Olympic heart-swelling moment; but feminist moments from the Olympics are sometimes less about people and more about institutions and the media doing the right thing.

Here are seven feminist moments in Olympic history that will make you want to punch the air (in a good way).

1900: The First Women Compete In The Olympics (In Skirts)

The first modern Olympic games, in 1896, was male-only; but, in a move of surprisingly progressiveness, women made their way into the competition at the second event, in 1900. There were only 22 of them, and they only featured in "ladylike" sports like tennis, sailing, and croquet, but they still made a mark; the first woman to win a medal, Swiss athlete Hélène de Pourtalès, was in a boat crew with her husband and his nephew, while the first individual gold medal for a woman went to the English tennis player Charlotte Cooper, who dominated the sport despite having to play in shirt, tie, and floor-length skirt.

1912: Fanny Durack Pays Her Own Way

The victory of Fanny Durack, the Australian swimmer, in the 100m freestyle at the 1912 Olympic Games was as much a triumph of will as it was a show of athleticism. Durack, an Australian champion swimmer, was restricted from competing at the Olympics by an Australian law that ruled it was "indecent" for women to swim at the same events as men; but she was a hugely popular figure in Sydney, where she trained and raced, and was determined to make it to the Olympics on her own. She raised her own passage with the help of a public appeal for money, convinced the swimming officials to lift the ban, sailed to Stockholm, and proceeded to win the gold medal, breaking the world record in the process. In these days of state sponsorship and huge nationwide support for athletes, it's a hell of a moment to remember.

1936: Louise Stokes And Tidye Pickett Are First African-American Women To Compete

American sprinters Louise Stokes and Tidye Pickett were pioneers both for feminism and for women in color in the 1930s. After missing out on the final American Olympic squad in 1932 thanks to a racial selection process (they were also kept separate from white runners and served food in their rooms), they were given their chance for the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Those, of course, were the extraordinary Olympics hosted in Berlin by Adolf Hitler, in which Jesse Owens produced a historical athletic performance to defy the Aryan rhetoric of the Nazi state. At the Olympics themselves, Stokes was replaced by a white runner once again, but Tidye was given the chance to compete, getting to the semi-finals in the 80m hurdles before falling at a hurdle and being eliminated. They were the first two African-American women to be selected for an American squad, and Pickett herself was the first to ever compete.

1991: IOC Rules All New Sports Must Feature Women

The International Olympic Committee, which manages and oversees the Games, decided to set a precedent for gender equality in the '90s, as more and more world sports applied to have a role in Olympic proceedings: The IOC ruled in 1991 that all new sports that applied to be Olympic had to be dual-gender; in other words, it had to have both men's and women's divisions. It's taken a long time for gender equality to really make its mark on the Olympic athletes, though; 2012's London Games represented the very first time in which every sport at the Olympics had female competitors as well as male ones. A report in 2013, though, pointed out that there was still significant gender difference in 2012, whether there were fewer female competitors than males in a sport, or the overall amount of athletes (6,068 men versus 4,835 women).

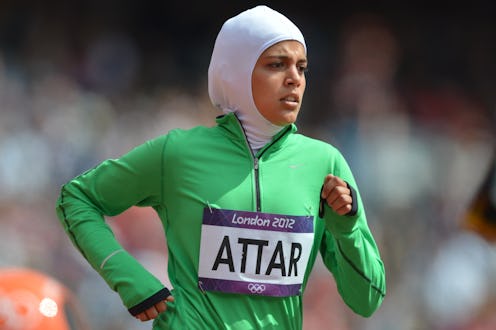

2012: Sarah Attar & Wojdan Shahrkhani Represent Saudi Arabia

London's 2012 Olympics represented something fairly significant for female participation in sports: the ruling body demanded that Saudi Arabia provide female athletes in order to allow any of its male ones to compete. At short notice, the country provided 19-year-old Sarah Attar, a long-distance runner, and judo competitor Wojdan Shaherkani, who was only 16 at the time. Attar recalled in 2016, "You get these people dedicating their lives for four years and eight years just to try and make an Olympic team. And here, somebody says, ‘Hey would you like to be in the Olympics?’" Attar came last in her heat and Shahrkhani was eliminated in a bout that lasted less than a minute, but their participation was hailed as a massive step forward for the reputation of a country that often refuses to allow women play sports at all. Attar is back for Rio 2016, accompanied by fencer Lubna Almomar, judoka Joud Fahmy and runner Kariman Abuljadayel.

2012: The BBC's Olympic Body Match

One of the most positive moments for body positivity and feminism came, not from the grounds of 2012 competition, but from a particular type of media coverage. The BBC in Britain ran an app on their website called "Your Olympic athlete body match" that was widely hailed as a huge step forward for public perceptions of "athletic" bodies and the diversity of fitness. Enter your height and weight, and chances were strong that it would match you to a serious athlete competing at the Games (my stats came up as similar to a champion shooter, a swimmer, and a 100m runner). The body positive movement is inherently feminist in its outlook, and anything that enables women (and men) of all sizes to see themselves as potential athletes is a pretty awesome step forward.

2016: The First Rugby Sevens For Women

Some people are calling the now-viral photograph of Germany's volleyball match versus Egypt the definitive feminist image of the Rio games: two teams, two different cultural ideas about dress, all extremely powerful women chasing glory. But in my personal opinion, one of the groundbreaking moments in Olympic gender history happened when the first-ever women's rugby sevens competition was held (and not just because Australia emerged victorious). It's a hugely symbolic thing: obeying the 1991 edict, rugby sevens, as a new sport, must have both male and female Olympic competitions. And rugby is one of the most "unladylike" sports that exists; you may remember the Australian rugby "war goddess" who kept playing after breaking her nose in 2015, earning her viral fame.

The inaugural rugby sevens represent the chance for women to compete on the Olympic stage in a sport that's as far transported from their 1900 long skirts and delicate croquet mallets as humanely possible. It's bloody, rigorous, dangerous, and requires huge skill. That, to me, represents the new face of Olympic gender equality.

Images: Bridgewater State University, UK Olympics/Wikimedia Commons