News

One Of The Roadblocks To Women’s Suffrage? Women

We used to call them defectors — the women who opposed such radical feminist goals in the 1970s as equal pay, fair access to education and jobs, and the right to control one’s own body. Their position was epitomized by conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, who led the fight against the Equal Rights Amendment (based largely on the fact that it would lead to unisex bathrooms) and who said as recently as 2014 that feminists “have this, I think, ridiculous idea that American women are oppressed by the patriarchy and we need laws and government to solve our problems for us.”

She wasn’t the first to resist the descent from the pedestal.

More than a century earlier, her ideological sisters were equally blunt about crusading against extending the ballot to women. As one Massachusetts leader explained, “We assert that women today are so protected by laws made by men, that they have nothing more to ask for legally.”

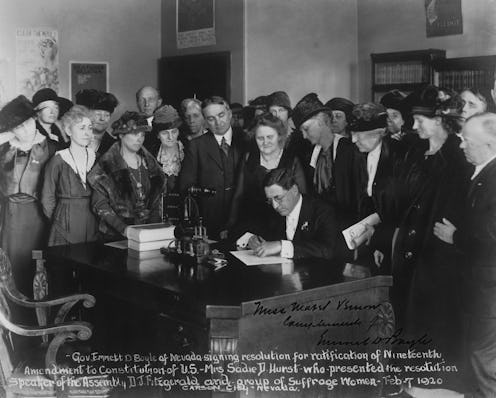

Today, as we celebrate the 96th anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution — and what most of us consider the nonnegotiable right of citizenship, the vote — it’s worth recalling the fierce, and occasionally loony, resistance of the anti-suffragist women. For decades, they were the majority.

“Women vote! Never!” declared the patriarchically self-identified Mrs. M.W.W. Sherwood in 1894. “Imagine the contradictory elements it would involve. … She is no longer [the man’s] wife, the mother of his children, the creature he keeps in the dearest corner of his heart. She is his opponent, his antagonist, the democrat when he is a republican…”

Yada yada yada.

Another group of women petitioned Congress in 1871 to vote against enfranchising women, because voting was “unsuited to our physical organization.” I have no idea what they meant.

For the most part, the “antis,” or “remonstrants,” as they were known, came from the upper class. As the unabashedly partisan authors of History of Woman Suffrage — Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Ida Husted Harper, Elizabeth Cady Stanton — put it, they “have dwelt since they were born in well-feathered nests and have never needed to do anything but open their soft beaks for the choicest little grubs to be dropped into them."

Their electoral snobbery, according to historian Ann Gordon, editor of the six-volume Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, was simply “an anti-democratic unwillingness to expand the electorate.” She noted that Stanton repeated the mantra of a New York remonstrant: “Our ignorant vote was already far too large for the safety and stability of our Government.”

Preserving that domain from the invasion of women — and minorities, and foreigners — turned as ugly then as it is now. Hostile postcards included images of suffragists being mocked, drowned, and crushed to death. And no one needed to shout, “Lock her up!” because some suffrage leaders were imprisoned and brutally force-fed when they went on hunger strikes.

Yes, for the right to vote.

Anthony, a frequent target of hideous caricatures and nasty name-calling, tried politeness and tact to win over her foes, but ultimately, called them what they were: hypocrites. “They forget,” she told a newspaper reporter in 1900, after nearly half a century of fighting for women’s rights, “that but for the suffrage movement they would not have had the privilege of coming before men in public to criticize and to ask that we be not given the things we pray for.”

Things turned so sour between the two factions that an 1897 article in the New York Times asked, “Do Women Hate Women?” The answer, from three prominent women, was decidedly "No." But the antagonism persisted.

And the aforementioned Mrs. Sherwood heightened the tension when she noted, “No class of human creatures are less apt to get along with each other than masses of women.”

Of course, the women who lobbied and agitated and demonstrated for the vote over more than seven decades got along just fine, despite some internal squabbles. There were disagreements about the best approach — federal or state legislatures? There were arguments over whether to focus solely on the vote, or to add other issues, like divorce and religion.

And there was some dissent about what they called themselves: suffragists or suffragettes?

“While the Suffragist plods along in the beaten track made by the great pioneers of the movement and contents herself with methods conservative,” wrote one young die-hard, “the Suffragette is militant… unwilling to wait for the ballot another sixty years. She wants it now and she wants it quick!”

In fact, the word “suffragette,” with its dismissive suffix — reducing everything to a frail and frilly offshoot of the original (Kitchenette? Leatherette? Bimbette?) — was borrowed from British women, who had co-opted it from male journalists, turning their belittlement into a battle cry. They also hardened the “g” — suff-ra-GET — to proclaim their intent to GET the vote by increasingly militant means.

On this side of the pond, a small group of New Yorkers adopted the word as their own bold statement of impatience, but the American suffragette crowd was a tiny minority, its noisier tactics largely rejected by the mainstream suffragists to whom we are indebted. Ultimately, it was a combination of both that broke the impasse in Congress, and when Tennessee became the last state to ratify the 19th Amendment in 1920, the front-page New York Times headline correctly read: "SUFFRAGISTS BLOCK FOES IN TENNESSEE; BELIEVE FIGHT WON."

The legislation that resulted — enacted by the government, of course — gave all women the right to vote, whether they wanted it or not. It will even allow Schlafly to cast her ballot for Donald Trump, the candidate she wholeheartedly endorses. That’s how democracy works. Thanks to the 19th Amendment, the rest of us can wholeheartedly vote against him.

Image: Everett Historical/Shutterstock