Life

A History Of Terrifying Clowns (You're Welcome)

The year 2016 will go down as a year of many things: the time when major news networks had to find a euphemism for "p*ssy" live on air, for instance. But one of its distinguishing factors across the U.S. and UK at the moment is a plague of "scary clowns," people dressing as the archetypal modern circus clown (with or without bloodthirsty makeup) and chasing around terrified passers-by. Multiple sightings have occurred across both countries of "suspicious" clowns, doing everything from talking oddly to children to wielding chainsaws and threatening schools. The reasoning behind this popular revolt against sense remains obscure; it's likely bored people in pursuit of viral fame and a thrill. But the origins of the clown as a terrifying figure actually go back further than 1980s horror films; the clown, fool, and similar figures have occupied a strange, outsider status in society in many civilizations, giving them unique power to startle and provoke.

Smithsonian traces the origins of modern clown-terror to two towering figures of the 19th century: Joey Grimaldi and Jean-Gaspard Deburau, both of whom were enormously popular clowning figures with well-known, tragic lives marked by violence and abuse. But the broader notion of clowning as a kind of dark mirror, reflecting society's worst aspects back to it under the guise of jokes, has a much longer history, back to jesters in ancient Egypt and Greece. Any study of Shakespeare, particularly of the tragedies, reveals that the "Fools" are the ones who tend to speak truth to power, a testament to their solid outsider status: famous Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin called clowns "life's maskers," saying that they have the "right to be 'other' in this world, the right not to make common cause with any single one of the existing categories that life makes available." Clowns are meant to be "other," to be outside the mainstream of things, and that can make them terrifying.

That history inflected both Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, the 20th century inheritors of the clowning on the big screen; concealed, often openly, in their slapstick antics and gentle personas was criticism of big societal concepts like war and mechanical progress. That outsider status is what created the potential for clowns to be the centers of horror. The modern concept of the terrifying clown, mostly derived from Stephen King's murderous Pennywise in It , isn't really about a benign childhood entertainer turned rogue; it's part of a long line of disturbing clowning figures, out to disrupt the order of things. Here are just five of its ancestors.

The Roman Funeral Clown

At the funerals of worthy and wealthy Roman citizens, the presence of one particular person was apparently invaluable: a jester (called a "mimus," in Latin) who would dress as the now-dead person of interest, and follow the funeral procession, imitating the follies of the deceased to make onlookers laugh. No, seriously.

"Imitating and ridiculing the bad habits of the departed," in the words of one expert, was the entire point of the ceremony for the mimus, and cemented the status of the corpse. He wasn't alone, either; it was the custom for the mimus to be preceded by "a whole platoon of clowns and buffoons, singing ribald songs and shouting very coarse jokes". All these people were being paid for the performance. The Roman historian Suetonius, hilariously, recounts that the emperor Vespasian's funeral procession was followed by the famous clown Faco dressed in imperial robes, who mocked Vespasian's legendary penny-pinching and asked the audience how much the funeral would cost him. There's something more sweet about this than creepy, to be honest.

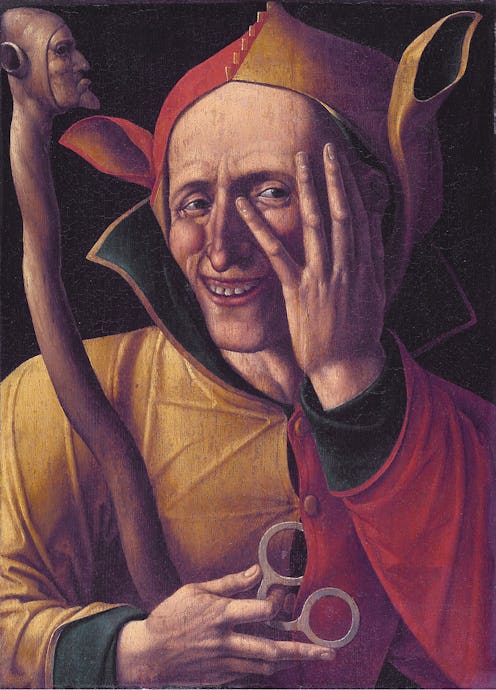

The Punchinello Of Commedia Dell'arte

The Italian Renaissance gave us many things, but one of the most enduring was the commedia dell'arte, a set of characters (most buffoonish) that would become the staple of clowning in the modern age. Anybody could play one of the parts if they adopted the correct get-up: sad, sweet clown Pierrot in white with pom-poms, Harlequin in diamond-shaped patches that eventually gained the character's name, and Punchinello or Puncinella with a giant stomach and an even bigger thumping-stick for his enemies.

Punchinello was the essence of the evil, scheming clown: the inspiration for the Punch of Punch & Judy shows, in which he could be anything from "a wicked villain who beats and kills for no reason [to] an angelic champion of good sense," he was originally a bit more straightforward. Punchinello, the Victoria & Albert Museum notes, "was the subversive, thuggish character whose Italian name ... may have developed from the word pulcino, or chicken, referring to the character’s beak-like mask and squeaky voice." He became much more famous on his own as a puppet and marionette throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and it's probably Punch's influence that means we still view clowns as carrying the tendency to be mercurial, mean, and unexpectedly violent.

The Indian Jester Who Triumphs Over Terror

There are plenty of stories in multiple folktale traditions of clownish tricksters who pretend to be utter buffoons and are actually shrewd operators: Anansi and Br'er Rabbit are brilliant examples. And this edge, the notion of the clown dicing with death, is possibly another aspect that's added to our general conception of the fool character as inherently slightly dangerous. Clowns in Balinese theatre, according to David Robb in Clowns, Fools & Picaros , are meant to be the servants of the gods, and try to reveal the inherent contradictions of the world: in that tradition, "good and evil are necessary and interrelated, as are death and life, heaven and hell, happiness and sadness." Accordingly, they have some incredibly close shaves; but one, from the Indian tradition, really stands out as hilariously dangerous.

The possibly-mythological clown figure Tenali Rama, who allegedly lived as jester to the medieval Indian court in the 1500s, had the origin story to end all origin stories. He apparently summoned Kali, a terrifying Hindu goddess who habitually wears skulls in a necklace, stole two pots from her, and then made a joke about snotty noses at her expense. Kali cursed him to be a jester for the rest of his life, but added that he was funny, so she wouldn't kill him. Clowns, it seems, dance very close to the edge of the knife.

The Terrifyingly Feminine Mother Folly

If you're wondering if female clowns were a thing, Mother Folly is at your service. She was a feature of carnival plays in medieval Europe, and allowed for something extremely threatening to run riot: femininity. Mother Folly was usually an elderly woman at the head of medieval carnival proceedings, which happened just before Lent and were accordingly completely mental.

The idea of a woman in charge of anything was suitably topsy-turvy for the medieval mind, but there was more; Christa Grossinger, in an examination of medieval art, finds that Mother Folly's shown as masked with a "full-moon face," emphasizing the fickleness of ladies and their inherent danger as powerful people. She could be a man dressed as a woman rocking babies, or with a bizarre phantom pregnancy; she could run riot and be lustful and bizarre. Mother Folly, in the phrase of another expert, "allows for the expression of aspects of the feminine that are normally repressed." And there's nothing more terrifying that a woman on the loose.

The Ridiculous Tudor Devil Clown

In the Tudor dramatic tradition, the Devil existed onstage as a villain; but he wasn't necessarily an unfunny one. There is, according to The English Clown Tradition From The Middle Ages To Shakespeare , a long argument about whether the Devil on the Tudor stage was actually meant to be a serious character. In reality, it looks as if the Devil was often actually a clown: comic, ridiculous, "irredeemably foolish," and prone to being outwitted even by the more traditional clowns and buffoons on the stage. The Devil and the stupidest character were often locked in a battle of wits, which resulted in somebody or other making an utter fool of themselves. Devil characters would also cause mild havoc and get the best comic asides.

Whether this was meant to make Tudor English audiences feel a bit more relaxed about the embodiment of Christian evil, it also points to something interesting: if the Devil himself is a clown, no wonder we still regard the entire clown idea with something of a shudder.

Images: Baths Of Diocletian, Wellcome Images, Maurice Sand, Rijksmuseum, Cosmographiæ Universalis de Sebastian Munster, Art Museum of Sweden/Wikimedia Commons