Entertainment

A Preacher's Daughter on 'Preachers' Daughters'

In the second grade, I went to Career Day at Mountainview Elementary dressed as a preacher. What a little weirdo, I was. A weirdo who wanted to be like her dad, because here’s a confession: like Taylor, Megan, Tori and Kolby of Lifetime’s original docu-series, Preachers' Daughters , I’m a preacher’s daughter too. I’m not Catholic and it’s certainly nothing I’m ashamed of, so technically that’s a pretty weak confession on my part. But being a preacher’s kid has a certain stigma around it: you’re either a wild child or those creepy kids in Mean Girls . The fact that I grew up as the daughter of a Baptist preacher in Texas is not particularly helpful to my “not crazy, I promise” case. It doesn’t seem to count that my parents were some of the least strict of all my friends and completely open minded to us making our own decisions regarding religion and morality. When asked what your father does, responding, “He’s a Baptist pastor, but he’s totally cool, and I turned out way normal,” doesn’t really roll off the tongue.

How interesting might this show be if it showcased a group of teenagers who happen to have a unique knowledge of Christianity, both the spiritual side of faith and the political side of the Church, and how they either conform to their parents’ beliefs or buck up against them. As it is, this show takes a look at what it’s like to drink and party a lot, or want to drink and party a lot, when you have very strict parents who happen to be preachers. To a much broader degree that it mostly ignores, Preacher's Daughters about knowing your parents’ beliefs, knowing their intentions for you and for the world, and actively defying those intentions because you feel strongly enough to do so. The interesting wrinkle of Preacher’s Daughters, or actually being a preacher’s daughter, is that disobedience is all at once a result of the strangling confines of religion, and at the same time, nothing about it at all.

Within the first few episodes of the second season each girl alludes to the idea that they don’t want to be defined by a religion or a lifestyle that was chosen for them. The implied follow up questions a better show might have asked are, Then, what do you want to define you? Would you be religious if your parents weren’t? These are questions I asked myself all the time growing up as a preacher’s daughter.

The entire Preachers' Daughters series seems to hinge on the idea that the more these girls misbehave, the more they buck their parent’s standards for behavior, the more interested we as audience will be. But I can get a show about wild partying anywhere I want, and MTV’s The Challenge perfected the formula by adding grueling competition to the mix about 15 years ago, so why would I look anywhere else? In that way, Preacher’s Daughters is a total missed opportunity to show what it’s actually like to be a preacher’s daughter, beyond simply rebelling—the complex relationship you develop with the Church and with faith; the point at which you have to decide whose beliefs you’re following, your parents’ or your own; and of course, in what ways that causes you to rebel. The show occasionally gets just a few things right, but misses the mark on exploring them any further:

The importance of going to church and being seen:

At one point, Taylor’s dad, a Pentecostal preacher and the strictest father, says, “Image is everything.” That’s an awful thing to say to a 17-year-old girl, but he is correct that public image is important. Being a preacher is like being a political figure; everything you do, and by proxy, everything your family does, is up for judgment. When you work in the business of morality, a church wants to know that their preacher is the most moral person out there, and their family is an extension of that. Be at church every Sunday, Sunday night, Wednesday night and for every special Youth Group outing, or you might as well paint “SINNER SPAWN” on your head and harness yourself to your preacher parent.

“Being a preacher’s daughter is like a full time job that I never signed up for.” – Taylor

Megan’s dad, Jeff is former worship leader with a plush day job that allowed him to wear all the terrible graphic tees his heart could desire, but he presently fired from that job and moved into ministry full-time. Jeff tells his daughter that when he becomes the Associate Pastor at their church, their whole family is taking on the job. She’ll have to dress better, act better, be more present and publicly support him. That’s the life of a preacher’s daughter. My own personal findings are that there are a lot less scandalous nights on Bourbon Street than Preacher's Daughters might imply.

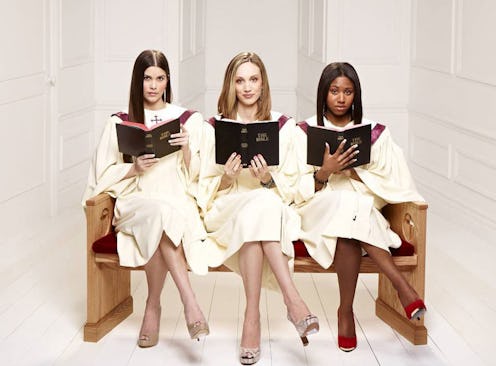

Images: Lifetime