Before becoming a less-than-satisfactory film in 2008 (followed by an even worse sequel starring The Rock) Journey to the Center of the Earth was a mystical science fiction novel that stood the test of time for 150 years. I contend it's one of the rawest, most beautifully written adventure tales of all time, matched only, perhaps, by Jules Verne's other works, including Around the World in Eighty Days and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

Written in 1864, Journey to the Center of the Earth came way before common gateway interface and 3D cinema featuring dinosaurs lunging at your face. The novel is grounded in history — but it's no less fantastical than its movie counterparts. Even without neon lights, Vanessa Hudgens or Dwayne Johnson.

The beauty of Journey is that it's the classic adventure novel. Professor Otto Lidenbrock, his nephew Axel, and their trusty guide Hans explore the earth in which we actually live, albeit a part of it that we are totally unfamiliar with. Its use of actual scientific fact and reasoning makes you feel as though the entirety of what you're reading is perfectly possible — even if not so plausible.

Okay, like most novels written in the Victorian era, bits of Journey are slightly problematic. When Axel and the Professor have set off from Hamburg and entered Iceland, Axel notes that their Danish hosts are "behaving like hunters, fisherman, and other rather uncultivated people," and that "sobriety was not one of [their] virtues." And let's not forget Grauben (Axel's love interest). According to Axel, "Reason has no part in [women's] lives," but Grauben is nonetheless the perfect lady: doting, caring, and faithfully awaiting his return home.

It would be unfair, though, to judge Journey or Jules Verne for succumbing to the prevalent views of the time, even when the blatant classism and sexism gnaw at your rationale. At the end of the day, this is a novel meant to inspire. Sure, it was probably meant to inspire predominantly men of the times, but today it's for everyone.

The first time I read Journey, I was in 7th grade. Prehistoric skulls and mysterious sea-life gripped me, just as they do today. But reading it back, there are many lessons to be learned — and many I wish I'd known back then.

Never abandon difficult tasks

Poking fun at his uncle, Axel says, "Professor Lidenbrock was a bibliomaniac in his spare time; but a book had no value in his eyes unless it was unique or, at the very least, unreadable." Sometimes the most difficult tasks — like the most difficult books to get through (Gravity's Rainbow comes to mind!) — are the most rewarding.

Pursue your crazy ideas

When Axel and the Professor find out that the ancient manuscript they've deciphered holds the key to traveling to the center of the earth, Axel dismisses it. "What a crazy idea!" But had he not put his fears aside and joined his adventurous (and oftentimes slightly deranged) uncle, there would be no novel. There would be no adventure.

"Science is eminently perfectible"

Professor Lidenbrock, upon hearing his nephew's scientific, logical concerns with traveling to the core of the globe, expresses to him that science is to be trusted, but only so much. "Each new theory is soon disproved by a new one," he says — ultimately trying to convey that seemingly impossible feats are never truly impossible at all.

One can be both timid and brave

Ignoring the Victorian implications of Grauben's characterization, Axel loves that she is one of the most timid, humble of people he has ever encountered, but also one of the bravest (it's Grauben who convinces him to go on his adventure!). In many ways, he is very much the same — a shy apprentice always in his uncle's shadow. But the novel is equally about finding one's courage as it is about humanity's mysteries.

Appreciate modernity's marvels

Something that didn't strike me upon first reading Journey at 12 was the sheer difficulty of the journey itself (even before things go a bit mystical). Getting from Germany to Iceland is nearly a month-long excursion, requiring trains, ships, and a lot of walking. Today, it's about a three hour flight. Granted, this may not have been a lesson Verne meant to impart in 1864, but it's definitely one to keep in mind today.

When heading on an adventure, take precautions

"We had a medicine chest containing blunt scissors, splints for fractures, a piece of tape of unbleached linen, bandages and compresses, lint, and a basin for bleeding — all rather terrifying objects — as well as a set of bottles of dextrine, medical alcohol, liquid acetate of lead, ether, vinegar, and ammonia." One cannot accuse them of being unprepared.

The world is full of wonders

Once in Iceland, Axel describes the island as a "huge natural history museum." He is fascinated by the beautiful mineralogical curiosities found all around him — by the volcanoes and the dark rock formations created from their eruptions. Earth's natural beauty transports him into a magical place of "sublime contemplation."

We all show affection differently

Once the journey has truly begun and the trio is climbing and digging and traveling in the pits of a volcano, Axel becomes severely dehydrated. Because he often describes his uncle as a cold, callous man, he is amazed and touched to learn that Lidenbrock has saved him the last of the water. This simple act of kindness goes a long way in reassuring Axel that his uncle does care for him.

One must always make time to be outdoors

After a few weeks of being underground, Axel and his uncle begin hallucinating, and quite frankly, going a bit mad. But as Lidenbrock explains, "External objects have a decided effect on the brain. Anyone shut up between four walls ends up losing the power to associate words and ideas." Being in the outdoors — taking in the air and the breeze and the smell and the landscape — isn't just inspiring, it's a must for mental health.

Patience is an epic virtue

Both Axel and Hans know that the Professor is a seriously impatient man. When he first discovers Arne Saknussemm's manuscript of the journey to the center of the earth, he begins preparations for travel immediately. Perhaps it was simply Verne's style, or perhaps he wanted to make a little joke out of Lidenbrock's persona, but it is not until we are two-thirds into the novel that the adventure truly begins when the trio finds a sea —an actual ocean (sand included) — hundreds and hundreds of miles below their starting point. Just as we want the Professor to show a little patience, so too must we be patient. And the wait is certainly worthwhile.

Know your roots

What most impresses Axel when they arrive at the underground sea is not the water itself or the "beach of fine golden sand." It is that the sand is "strewn with those little shells which were inhabited by the first living creatures." Because Axel and his uncle as so scientifically minded, and true believers in evolution, seeing evidence of some of the first life forms ever is monumental. Knowing where you come from (whether in terms of evolutionary history, or simply culture and heritage) is essential to knowing yourself.

Always appreciate things that seem weird

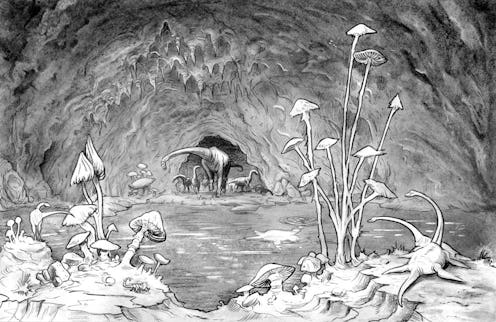

As the journey progresses and the group of travelers find themselves at the center of the earth, they are suddenly bombarded with "mushrooms thirty or forty feet high," "tree-ferns as tall the fir-trees in northern latitudes," and "lycopodiums a hundred feet high." To most people on mainland Earth, the overgrown flora might seem bizarre and unnatural. But to the explorers, they are preserved and marvelous bits of history, tucked away in the secret center of the planet.

Monsters are never far behind

So maybe the chances of encountering a monster with the snout of a porpoise, head of a lizard and teeth of a crocodile aren't grand. Nor a serpent with a cylindrical body, short tail and four flappers spread out like oars. As far into the core of the Earth as they are — and as far from humanity — Axel, the Professor and Hans weren't expecting to encounter these terrifying, albeit fascinating, creatures. But "real" monsters are never far behind in reality, be they in the form of cruel people or emotional distress. Protecting yourself, and your heart, should never be forgotten.

Never underestimate human beings

As the journey is ending, and the guys are on their way back toward the surface, they encounter what appears to be an oversized human skull. To Axel, it seems impossible that any human being be able to survive as far underground as they are — surrounded by so many larger and more dangerous beasts. But there is no doubt it was an "absolutely recognizable human body." A man-like ape, or an ape-like man they do not know, but they all leave feeling as though the human mind, body and soul are capable of a lot more than we sometimes believe them to be.

People will believe what they want to believe.

Upon returning to their home — and becoming distinguished amongst the scientific community as well as pretty much everyone else — Axel notes, "Such is the conclusion of a story which even those people who pride themselves on being astonished at nothing will refuse to believe." At the end of the day, people will always choose to believe what they wish to believe, no matter the evidence at hand, or the convincing tales you tell. Sometimes the best course of action is, as Axel says, to be "hardened in advance against human incredulity."