If there’s any magic in this world, Neil Gaiman knows where to find it. His novels and comics imagine ancient gods roaming our cities and suburbs disguised as mob bosses and morticians; in which Death incarnate is a spunky, impulsive Goth girl; in which nightmarish universes exist behind the mirrors in our homes. And if you are one of those poor unfortunate souls who doesn’t believe in magic, a trip into any of the prolific writer’s works will amend that shortcoming.

Gaiman’s enchanted worlds, even the truly nightmarish ones, are surely more magical and desirable than our own. But at the end of these thrilling journeys — once you’ve reached the ocean at the end of the lane; once you’ve shaken hands with the Sandman; once you’ve safely returned from the universe’s underbelly — Gaiman insists on turning that wiser gaze inward, on casting that spellbound view on your own, mundane setting.

“There are still things that profoundly upset me,” the writer/sage says in the introduction to Trigger Warning, his new collection. “They never get easier, never stop my heart from trip-trapping, never let me escape, this time, unscathed. But they teach me things, and they open my eyes, and if they hurt, they hurt in ways that make me think and grow and change.”

This is the promise Neil Gaiman bestows on his reader, the pact between storyteller and adventurer: some of the things he writes about are scary and sticky and confusing. But you will always come out the other side utterly changed, both wiser and more naïve; both ready to take on the world, and less sure of what this world secrets away in its many nooks and crannies.

You’ll find a story in everything

Neil Gaiman was the first fantasy writer I fell in love with, because his stories, while always gleefully magical, are essentially rooted in the “real world.” Gaiman’s stories are never fantastical just for fantasy’s sake; the writer explores these worlds earnestly, with the intention of revealing our own truths and fears hidden within the folds of our realities. Take Coraline, for instance, Gaiman’s 2002 novella. The title character, an incredibly perceptive, oft-ignored little girl (who everyone mistakenly calls “Caroline," ugh), discovers an alternate universe hidden behind a mysterious door in her living room. That alternate universe isn’t so terribly far off from the mundane universe: it’s a little more colorful, a little topsy-turvy, and a lot more horrific (i.e., Coraline’s “Other Mother” looks just like her real mother, albeit with buttons for eyes and a penchant for squirreling little children behind mirrors till they rot and die there.)

In all of his work, Gaiman stuffs his prose with magic and wonder, casting an enchanting spell over even the most unsuspecting places; like in his poem “Making a Chair,” which manages to make that process feel like something special and important, something worthy of being written about, and definitely not like making a chair. It must be so fun to be Neil Gaiman!

Stealing Gaiman's worldview is a gift, an opportunity to make your own boring life feel like an Important Adventure: a puddle of yellowy slush will become a shimmering portal to an underground world; your surly barista, you’ll realize, is quite possibly a suffering rebel mage who’s been unceremoniously cast out of his own universe. There is so much, Gaiman repeatedly teaches us, that we do not see of this world, simply because our eyes aren’t open to these hidden miracles. Don’t be afraid to open up — you just might find something worth writing about.

You’ll be wary of thresholds

Neil Gaiman takes his thresholds very seriously: in Stardust, an annual Faerie Market is held on the far side of the town Wall’s eponymous wall. And in Neverwhere, which plumbs the spooky depths of London’s underground world, a girl called Door whisks Richard Mayhew away on a terrifying subterranean journey.

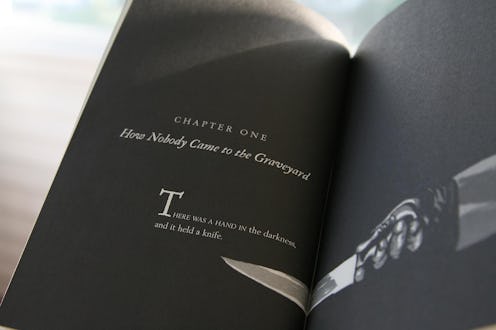

True to the hero's journey archetype, in most of Gaiman’s work the sh*t really hits the fan when the hero(ine) crosses a shady threshold. Once Coraline enters the door she should not have entered, she encounters a world where everything is horrific, but also where the veil between the living and the dead is torn apart. In Gaiman’s children’s novel The Graveyard Book, the ironically lively inhabitants of an ancient graveyard cannot pass the cemetery’s gates. Only Nobody Owens, a small boy who the spirits take in as their own after his family is brutally murdered (children’s books are pretty dark these days), can pass between the gates.

It takes a special character to be able to transcend worlds: he must be an outsider, like Bod Owens; she must be open to seeing more than meets the eye, like Coraline. These intrepid characters are fearless, but compassionate; they’re scrappy, maybe even aimless, but hungry to discover the unknown. Also, it doesn't hurt to have a running dialogue with spirits and/or mythological creatures, so maybe pull out that old Ouija board.

You’ll reevaluate your conception of “genre”

Neil Gaiman is probably the closest thing the modern literary scene has to a rock star. He’s a cult icon, followed by young women dressed in black, eyes smudged with kohl, necks heavy with gold ankh amulets. Followed by tattooed, neon-haired, Dr. Marten-shod punks toting Philip K. Dick and H.P. Lovecraft paperbacks in their pockets. Followed by stay-at-home dads and sleep-deprived working moms, swooned over by their perky 4-year-old daughters and snot-nosed 10-year-old sons.

What is the secret behind Gaiman’s unfaltering popularity? What makes a twenty-nine year-old Goth chick obsess over the same novella being greedily devoured by a third-grade boy? One possible explanation for Neil Gaiman’s wide appeal is his highly distinctive style — a mix of fantasy, horror, camp, slapstick comedy, and magical realism — which is inspired by fairytales, mythology, and pop-cultural influences in equal measure. Neil himself (@neilhimself) seems to be a divinely open channel, an equal-inspiration-opportunist whose magpie tendencies result in satisfyingly cohesive works.

There’s something for everyone in Gaiman’s extensive bibliography. But no matter what you choose — from his delightful picture book Fortunately, the Milk, to the highly-pigmented world of The Sandman to the inspirational Make Good Art — you’re gonna get more than you bargained for. Gaiman’s work is accessible enough for dabblers but extensive enough for diehards, and it’s this acceptance of all ends of all spectrums that makes Gaiman so special.

You’ll learn not to be afraid of the big, bad world

First and foremost, a Neil Gaiman character worth her salt must be brave and compassionate. Without these combined traits — like a wide-eyed sense of wonderment wearing combat boots — nothing would ever happen in a Neil Gaiman story. It’s kind of like how nothing happens in your own life when you’re too scared to do new things and/or too lazy to get off your couch. Even if Gaiman's characters felt crippled by fear, beaten down by daily life, or neglected in favor of more obvious heroes, they all overcame those imaginary obstacles and made stories happen. When reflecting on Coraline's rampant popularity, Gaiman says, “I do not know why it has worked so well…I think it’s because, at the end of the day (which is twilit and is about the time when the bats come out), it is not a story about fear, but one about bravery.”

Inherent in all of Gaiman’s stories is an appeal to the outsider, the orphan, the disillusioned and the dispossessed to work past their obstacles. In all stories, obstacles provide an opportunity: embrace the fear. Exploit it. Prove yourself wrong. Discover something magical in the process.

You’ll learn that passion will take you far

If you haven’t figured it out by now, I really, really love Neil Gaiman. But I think it's the writer's passion that really motivates me to plumb the depths of his frankly terrifying bibliography. Gaiman's love for words is electric, and his need to share those words in the most generous and energetic and thorough way possible is profound. He lavishes love and attention on each of his characters, on each of his scenes, on each of his word choices; and, in doing so, he extends that same compassionate attitude toward you, the dear reader.

Neil Gaiman is obviously heeding his own now-viral advice to “make good art,” to not half-ass anything, to approach both your passions and your fears with an open heart. As he very charmingly shared, “If you have an idea of what you want to make, what you were put here to do, then just go and do that.” Simple, right?

Image: sharyn morrow/Flickr; Steel Wool/Flickr; Neil Gaiman/Twitter; Giphy (5); WiffleGif