News

A Timeline of "Bloody Sunday," 50 Years Ago

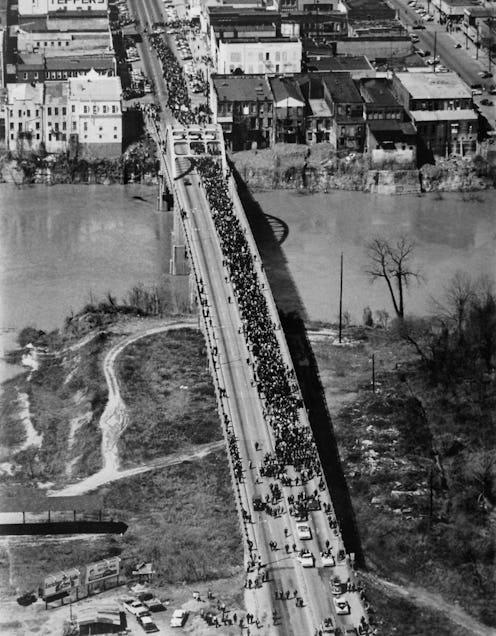

Saturday marks 50 years since marchers in Selma, Alabama were met with violent force by a cabal of white law enforcement officers, a clash that precipitated the passage of the Voting Rights Act. I'm talking about "Bloody Sunday," maybe the foremost flashpoint of the 1960s civil rights movement. Here's a timeline of the "Bloody Sunday" march, an event every American should know about.

Led by present-day Democratic Representative John Lewis of Georgia, then the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), some 600 marchers set out from Selma in a planned march to Montgomery, Alabama's state capital (itself home to countless instances of racial oppression throughout the 1960s, as well).

En route to Montgomery, however, they had to chart a course across the Edmund Pettus bridge, so-named for former Senator, Confederate officer and Ku Klux Klan leader Edmund Pettus. And as they strode towards the other side, they saw a throng of white faces waiting for them, ready to start doling out violence.

Marching At Risk Of Murder

A necessary prelude to any conversation about the Selma march, especially as it highlights just how much present danger everyone was in — the American South in the 1960s was still home to lynching and pervasive racist violence, especially directed at those black residents who tried to exercise their right to vote. While many of us now take them for granted, those marchers were willing to risk their lives in the quest for full, fair voting rights for black Americans.

And the potentially life-or-death stakes were obvious — the killing of Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi was just two years prior, an awful incident which galvanized civil rights activists from all strata of society. Legendary Boston Celtics center Bill Russell, for example, traveled to Jackson to run an integrated basketball camp, a show of solidarity and courage in the face of murderous racism. For perspective, Russell was the dominant basketball force of his time — it was as if LeBron James had gone to Sanford, Florida after the Trayvon Martin shooting, while also at considerable risk of being slain himself.

It wasn't as though the pro-civil rights side was racially uniform, either. Many white citizens were spurred to action by the daily brutality endured by their black brothers and sisters, a point hammered home by the above image — a sea of faces, mostly black but some white, staring down a racist posse.

"They Came With Nightsticks"

As the marchers crossed the bridge, they were met with an imposing sight. But they stood their ground, nonetheless, hewing to the principles of nonviolent resistance advocated by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. — rather than actually fighting back, exposing the brutality of the Alabama state troopers and local police through passive resistance. Armed with teargas, clubs and some riding on horseback, the assembled cops unleashed hell on the peaceful protesters, sending 17 people to the hospital.

Among those badly beaten was Amelia Boynton (now Amelia Boynton Robinson), who was photographed after being knocked unconscious. In a conflict that hinged so strongly on winning the sentiments of an often-ignorant white majority, the photo proved to be huge — it drew widespread attention, burning Bloody Sunday into the minds of those who saw it.

She's still alive to this day. According to the Los Angeles Times, her age isn't precisely known — somewhere between 104 and 109, they say — but her voice hasn't faded.

I was taught to love people, to excuse their hate and realize that if they get the hate out of them, that they will be able to love. After Bloody Sunday people began to wake up.… and those who have arisen because of our Bloody Sunday have excelled.

Lewis was also badly beaten in the assault, a fact he recalled while speaking to NPR's Neal Conan back in 2010:

And the major paused for about a minute, and he said, troopers advance. And you saw these men putting on their gasmasks. They came toward us, beating us with nightsticks, bullwhips, tramping us with horses, releasing the teargas. I was hit in the head by a state trooper with a nightstick. My legs went from under me. I thought I was going to die. I thought I saw death.

I had a concussion there at the bridge, and I don't recall 45 years later how we made it back across the bridge, crossing the Alabama River back to this little church that we left from. And when we returned to the church, the church was full to capacity. More than 2,000 people outside trying to get in to protect what had happened.

Two Days Later, Turnaround Tuesday

That wasn't the last time the protesters journeyed to that bridge, though the next encounter was already planned to be symbolic. As detailed by CNN, a second procession led by Dr. King headed out to the Edmund Pettus bridge on March 9 1965, where they were met with the same sort of armed resistance they'd seen on March 7. No melee ensued this time, however — the protesters simply turned and headed back over the bridge.

It was later that day when violence struck, and contrary to what you might assume, it wasn't a white-on-black crime — Unitarian Universalist minister James Reeb, who was in Alabama to participate in the activism, was ambushed and badly beaten by KKK members. He ultimately died from his injuries.

Lyndon Johnson Calls For The Voting Rights Act

In perhaps the most fondly recalled speech of his presidential tenure, Lyndon Johnson responded to the violence in Alabama with his "The American Promise" address. Calling for Congress to pass a Voting Rights Act, and stirringly employed much of the same historic language — and indeed, a signature phrase — used by Dr. King.

In our time we have come to live with moments of great crisis. Our lives have been marked with debate about great issues; issues of war and peace, issues of prosperity and depression. But rarely in any time does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself. Rarely are we met with a challenge, not to our growth or abundance, our welfare or our security, but rather to the values and the purposes and the meaning of our beloved Nation.

The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation.

... Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.

While it took a while — it wasn't passed and signed into law until months later, in August 1965 — this push by Johnson resulted in the passage of the Voting Rights Act. But, for all his support was crucial, it's impossible to know how it would've turned out if not for the bravery of those activists, staring down a wall of white police on the Edmund Pettus bridge that day: March 7, 1965, "Bloody Sunday."

Images: Getty Images (3)