Books

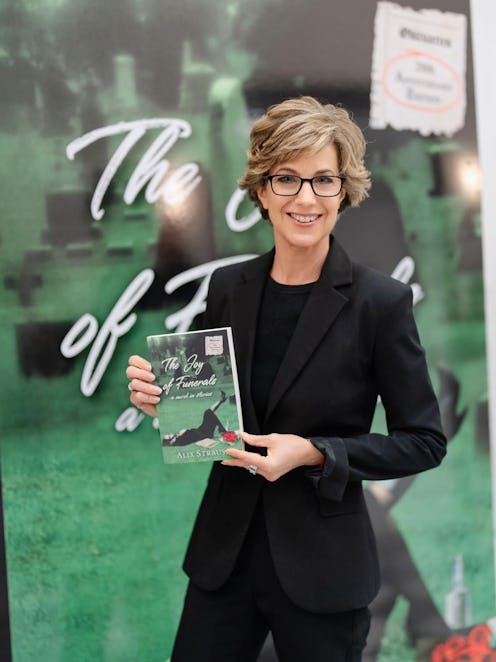

Alix Strauss Still Feels The Joy Of Funerals

Twenty years after the release of her debut book, The Joy of Funerals, Strauss believes there’s more to mine from these ceremonies than ever.

For many years, writer Alix Strauss harbored a secret. She was absolutely, thoroughly enamored with funerals. “When you first say to people, ‘I really love funerals,’ you get a very strange look,” she says. “They’re not really sure if you’re serious.” People would often respond with condemnations like, “That’s an awful thing to say.” But when Strauss elaborated — explaining that as an only child, and without much of a relationship to her extended family, these were the only times she could connect with her relatives — the tides would turn. “Once you don’t seem like a sociopath [who’s] scraping the dead bodies for DNA result, their face lessens and expresses sympathy and understanding. It’s such a universally understood thing [because] everyone has issues with their family.”

Strauss ultimately channeled her unique yet understandable fascination into her debut novel, The Joy of Funerals, which first published to great fanfare in 2003 and was reissued this fall. The book follows Nina, a thirty-something who attends other people’s funerals in the hopes of bonding with mourners. But Funerals is also populated by other achingly honest, often hilarious portraits of lonely women. Like the one who mourns her dead husband by having sex with men who are also bereaved, or another who attends the shiva of her psychiatrist’s widow, very much uninvited.

While Strauss was just as unsure of how people would respond to her book as she was sharing her secret all those years ago, its publication has been one of the most cathartic and rewarding experiences of her life. “Shockingly, it resonated with a lot of people,” she says of the reaction to the initial print and the later reissuing. “We are still grappling with the [same] issues. We are not well, we really are hurting. And if we don’t connect on something [culturally], at least people can connect with these characters and realize, hopefully, they're less alone.”

Below, Strauss reflects on family dynamics, writing your own vows, and Amy Sedaris.

Warning: This Q&A contains details about suicide which some readers may find triggering.

The Joy of Funerals came out of an essay you wrote for the New York Times Magazine about why you, as an only child, loved attending funerals. Prior to writing the essay, how aware were you that this “joy” wasn’t a weird quirk, but rather something deeply rooted in your lived experience?

I definitely understood that I experienced a funeral very differently than most people. [My parents] really didn’t create a family support system for me, which they absolutely should have. And that was really on both sides, my mother and my father. So that first funeral [I attended at 13], which was for my grandmother, I didn’t realize the sadness part of it as much as I realized this “excitement” of connecting with so many people that I was related to. It was very impactful.

Then, all those years later, when I was turning 30 and writing the piece, it [led to] a very big understanding of everything. It changed my life and shaped my fascination with family dynamics. Like yesterday, I was at Bloomingdale’s looking at shoes, and two of the three sisters in this family and their mom sat down to look at shoes. I thought, “I’m watching an experience I will never be privy to. I’m never going to have that experience.”

On the flip side of the coin, you also spent a portion of your career covering weddings for the New York Times. Weddings are vastly different ceremonies than funerals, but they’re rituals rooted in families nonetheless. What drew you to them?

When I was covering weddings, I wasn’t as single as I am now. So it absolutely brings up other issues of not being in love, or thinking I would be in a different place, or still seeing a lot of families. I’m still seeing this experience that I’m certainly not a part of. And I get to know my couples very intimately. So you’re witnessing these very intense, intimate moments the same way, in some sense, you do in a funeral. They’re both really fascinating rituals and fascinating experiences [because] it’s the other time that emotions are going to be so extreme.

Do you have a favorite version of how either ritual is done, having spent so much time considering both?

I definitely like the people who write their own vows. This is your moment to really speak from your heart. Everybody’s love story is different, as universal as it is, and everybody’s vows are different. I love listening to them. The eulogies, if you’re going on that same premise, are just as heartfelt and beautiful and also often give you an added level of intimacy and something else you didn’t know about the person.

So there are people who are at a wedding and may not have known this exact piece of information that the bride or groom are sharing. There will be people at the funeral who are learning something different about the deceased because they didn’t know every facet of their life. But you’re still hearing this great emotional story, so to speak.

Your second book, Death Becomes Them: Unearthing the Suicides of the Brilliant, the Famous, and the Notorious, also examines our societal fascination with death. Why do you find death such a rich territory for writing?

When you commit suicide, it’s the one decision you can’t take back. And it affects so many people. For these famous people specifically, it also made us feel part of something bigger than ourselves. There was this community grieving that even if we didn’t know them, we knew them. I think there’s something horrifically heartbreaking about how hard life is, especially now. We are all just walking around grieving.

The way that someone chooses to [die by suicide] was also very interesting to me. From the person who writes the note, to the person who doesn’t. The person who jumps out a window, to the person who slits their wrists in a warm bath. The person who drinks themselves into a comatose state and takes a handful of pills beforehand. They were all different but they were all the same — and that was fascinating, too.

That reminds me of a piece of advice Amy Sedaris gave in New York magazine recently that I really took to heart: “Assume everyone is grieving.”

I love being in the same sentence with Amy Sedaris. If I thought the world was on fire before October 7th, it's nothing to where we all are now. And it was so much for us just to come out of the pandemic. It's so interesting, too, because there are no classes in how to love [or grieve]. It’s just so hard to get through for some people, for a lot of people.

What do you hope those who are struggling to live and grieve today find in your book?

This was the first time that I really went back to the material in 20 years and I was shocked at how little had changed. I was shocked that we are still grappling with these issues. We are not well, we really are hurting. And if we don’t connect on something [culturally], at least people can connect with these characters and realize, hopefully, they’re less alone. There’s nothing wrong with them. They’re just trying to survive like all these other characters are.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741. You can also reach out to the Trans Lifeline at 877-565-8860 or the Trevor Lifeline at 1-866-488-7386, or to your local suicide crisis center.