Books

What Would Your High School Self Think Of You Now?

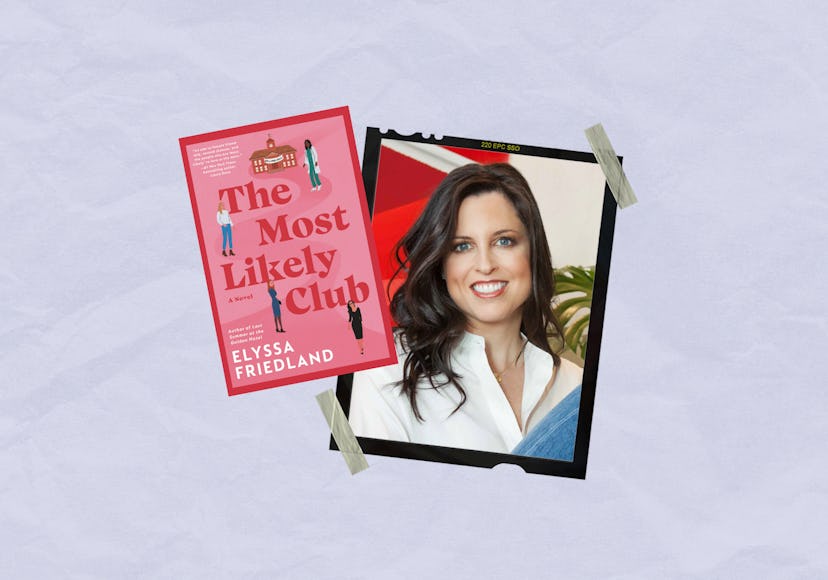

Elyssa Friedland’s new novel, The Most Likely Club, takes on thwarted millennial ambition.

Elyssa Friedland has made a name for herself writing novels that are fun to read while homing in on how difficult it can be to interact with other people, even people we actually like. (Her first book was titled Love and Miss Communication.) Now that she’s covered dating and marriage, extended family and real estate, Friedland’s fifth novel, The Mostly Likely Club, out Sept. 6, takes on themes that feel particularly timely as the oldest millennials turn 40: What does it mean to fulfill your potential? Was anything young women in the ’90s were promised about their futures actually true?

The setting indicates that Friedland knows her audience: a Connecticut high school’s 25th reunion for the class of 1997. The four protagonists have remained friends since high school, even as their lives have diverged. Priya is stretched to her limit between her career in medicine and a family domestic load that her surgeon husband seems not to realize he could share. Tara, once destined to be a star chef, is teaching cooking classes to kids on Manhattan’s Upper East Side after making a #MeToo accusation that ended her restaurant career. Melissa, who left high school with political ambitions, is divorced and walking on eggshells trying to stay connected to her teen daughter. Suki alone made it big, developing a wildly popular app that superimposes celebrity makeup looks on the user’s face, complete with tutorials and product links. Except now she is weathering the types of criticism that seem exclusively reserved for women entrepreneurs and CEOs — from young female customers and commenters.

At the reunion and in its aftermath, the four women take stock of where the past two decades plus have taken them, and ask what it would mean to change course. Bustle spoke to Friedland about yearbook superlatives, the pressure to write characters as role models, and the parts of high school that never leave you.

What did you get to do with this book that you haven’t in your previous work?

Focus exclusively on women and friendship. My first book had a single female narrator and a sort of narrow scope — she was very much modeled on me. In the second book, about a marriage, I gave equal footing to the husband and wife. And then in The Floating Feldmans and Last Summer at the Golden Hotel, I really dove into family, with these very big ensemble casts that spanned across generations.

Here, I write about four women who are exactly the same age, obviously — very similar to my age — all dealing with the reality of being a woman in her 40s. It’s complicated for each of them in very different ways.

1990s nostalgia has never been more popular, but superlatives are a very specific and representative artifact of 20th century high school. Why did you choose that frame?

It was just a neat device to have people look back and be like, “Oh, my God, I haven't thought about that in 20 years. How did we change from when we were that age to this age?” It was a fun entry point into the much larger story I wanted to tell.

Did you have superlatives in your high school yearbook? They weren’t allowed in mine.

We had them. I did an interview recently where I was asked “Do you think superlatives are a bad idea?” I actually don’t. Compared to the harshness of social media, superlatives are generally nice. They appear in a yearbook that’s overseen by a faculty adviser and published through the school. So they’re largely positive. I have a favorable to neutral view on high school superlatives.

Did any of the Most Likely Club characters’ experiences feel especially important to you to explore?

They all were in different ways. For me personally, it was cathartic to write Priya, whose life is probably the closest to mine. She’s a working professional, her husband’s a working professional, and they have three children. On paper, it looks great, but she’s doing 99% of the child care, the forms, finding the baseball coach, the SAT tutor, blah, blah, blah. It’s all falling on her, despite the fact that they have the same education and basically the same job.

That’s something I think about all the time. I’m not the primary breadwinner, but I definitely work as much as my husband does. When we have serious talks, I ask, “Why is it that I’m the one who knows what our kids’ shoe sizes are? Why do I know when they’re due for the dentist?” And of course he’ll do whatever I ask him, he’s a good guy, but it’s mental work just to know to ask, to anticipate what they need.

Tara is from a stereotypically Connecticut family — their name is on the high school gym — but her adult life contrasts virtually every aspect of her upbringing. She is not only gay and ambivalent about her kind, lovely girlfriend, but she also isn’t that interested in having kids. That doesn’t directly contradict the marriage plot, but isn’t a core trajectory for a character in so-called women’s fiction. How did you decide to include that storyline?

Tara’s straying from the life her parents want for her was important for me to explore because it dovetails with her financial dependency on them. If she didn’t rely on them for money, she’d feel freer to live her life openly the way she wants to. I find a surprising number of 40-somethings still live under their parents’ thumb, whether for financial reasons or simply because they are accustomed to seeking approval.

On the point of having children, I really wanted to emphasize that you don’t need to procreate to be a full-fledged woman. At least one of my characters needed to feel that way, especially at a reunion, where women so often asked, right off the bat, “So how many children do you have?”

Melissa’s reckoning with her life since high school feels the most complicated. What was the purpose of giving her a teenage daughter at the same school beginning to experience the meanness that high school social life so often entails, while Melissa, running the reunion, revisits her own high school social world?

I wanted to explore the way that, when you have a daughter, and she’s getting older, you start having vivid memories from your own childhood. She’s going through stuff — upset because whoever doesn’t call her, or she’s left out — and you have gone through it exactly. You’ve seen this story before. But it doesn’t matter; you can’t protect her. She has to go through it. You want to be like, “No, you don’t understand, those kids are losers,” but she’ll just be like, “You’re stupid, Mom. You don’t know what you’re talking about. You didn’t have Snapchat. You don’t understand.”

Isn’t that true, though? Social media has profoundly impacted adolescence, especially for girls.

I think it’s interesting that we are living in a different world — our kids are growing up with social media, and we didn’t — but the scripts are the same. It’s not like we didn't feel left out. It’s magnified now, sure, but hating your body when you’re a teenage girl, we had that too, even before we looked at a million pictures online. And we got left out of parties and felt like sh*t too, even without seeing the party on Instagram.

And that’s all still happening for Melissa, right? She finds out that she’s been excluded from a cocktail gathering essentially because she’s single, and she certainly still hates her body.

Yes, she still hates her body.

Actually, I've been sort of irritated with a couple of online reviews being like “It’s terrible to read about a woman who hates her body.” I don’t understand why you can’t write about someone who hates their body.

Trying to lose a few pounds, or a lot of pounds, before a reunion is pretty common. So to say that it’s unrealistic, or that it’s hard to read about a woman who doesn’t love her body… I sometimes feel like people are not being honest. They’re like, “Oh, but the friends weren’t always there for each other.” You’re really lucky if you have friends that have literally dropped everything to help you at every single minute and have never put themselves first, or felt jealous of you, or you felt jealous of them.

People often decry the expectation that female characters be “likable,” but the reader reviews you just described suggest a slightly different expectation: that characters be role models. The implication is that if characters engage in behavior harmful to themselves or others, it validates that behavior, or even represents an endorsement of that behavior on the part of the writer. Do you feel pressure from readers, or anyone else, to make your characters “good influences”?

I really don’t subscribe to writing characters who double as role models. Some of my characters might, but not because I set out with that intention.

The fact that I write about Melissa dieting pretty severely ahead of the reunion doesn’t mean I think it’s good. It’s not like I applaud her for being obsessed with her weight. I chose to make her someone who’s very insecure about her body. I did that to show that some of the scars from high school leave a mark. Think about kids who stutter and get made fun of. Even those who overcome the stutter still may not feel confident speaking in public. People who weren’t good students and then become really, really successful can still carry a bit of insecurity. They can’t let it go because that injury happens at such a vulnerable age.

The question of likability suddenly looms large for Suki, who combines the quintessential #girlboss and the canceled icon we’ve seen in characters like Jennifer Anniston’s on Morning Show. Why was it important to you to have one character take this path?

The experience of being a woman with a really big job has always fascinated me, although I’m very pessimistic about it. I don’t think that ambitious, powerful women will ever be that well received. I’m just not optimistic that in our society, a Fortune 500 CEO who’s a woman and a Fortune 500 CEO who’s a man will be treated the same, receive the same feedback, and be described the same way by colleagues and the media.

I wish I could soften that by being like, “Oh, but I think we’re headed in the right direction.” I actually don’t. I don’t know that that will ever change. I think that some things are just so deeply wired in our society that we’re kind of doomed.

Early in the book, on FaceTime with her old friends, we see Suki at work, correcting assistants, issuing directives. After the call, her friends reflect that she doesn’t seem happy. You say that you don’t think successful women will ever be treated equally by others, but are you suggesting in this scene that professional success at that level is inherently unfulfilling?

I wouldn’t say so. For a man or a woman, if you’re in a really powerful job, you’re really stressed. Maybe the woman’s more stressed because she’s balancing more or she’s not being perceived the way that she thinks she’d be perceived if she were a man. But no matter who you are, you have employees. You’re a public face. That type of professional success is complicated for anyone. It’s normal to not always be super happy.

Please talk about the Make App and whether you are launching it as a side hustle.

I was just on the phone with a friend who read the book, and she was like, “You’re a great writer, but of all your ideas, this one’s definitely the best.”

I wanted a female-oriented business. I was thinking a little bit about Sara Blakely and Spanx. She made a ton of money supposedly trying to help people but basically telling them, “It’s not so nice to be fat, so better to suck it all in.” This is a similar thing. I don’t think it’s a horrible business that Suki’s running by any means, but she is making money taking advantage of a celebrity obsession and an obsession with beauty.

But yes, in a business sense, Make App is a great idea. I wish someone would do it. Not me.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This article was originally published on