Books

Living While Black Offers Rigorous Analysis Of Racial Trauma – EXCERPT

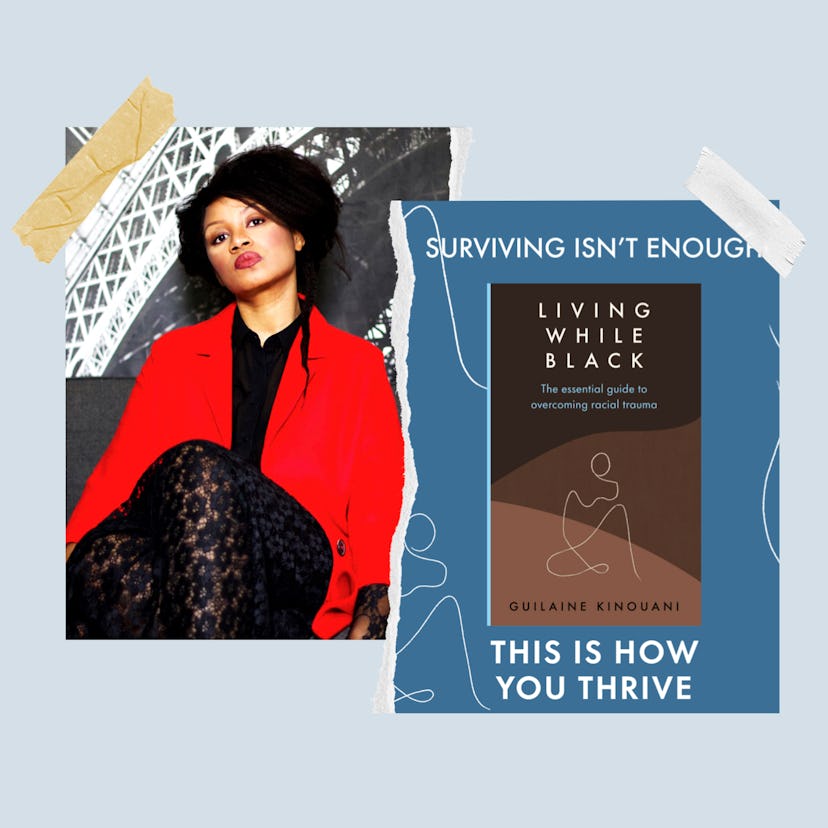

The book is the culmination of 15 years worth of work from psychologist & therapist Guilaine Kinouani.

Described as “revelatory, necessary, and brilliant” by Queenie author Candice Carty-Williams and “an incisive and important book” by The Good Immigrant’s Nikesh Shukla, Living While Black is a culmination of 15 years worth of study and work around racial trauma from psychologist and therapist Guilaine Kinouani.

As Penguin explains, Living While Black is a continuation of the work that Kinouani began on her blog, Race Reflections. Over the last decade and a half, Kinouani “has helped hundreds of Black people to protect their mental and physical health from the harm of white supremacy.”

The book, which will be published on June 3, brings together case studies, research, and practical coping techniques to give readers a comprehensive guide for navigating racism and the long-term impact it can have on their mental wellbeing. It also offers anti-racist allies the opportunity to dig deeper into the experiences of Black people and understand what more they could be doing to tackle injustices they may not even be aware of.

Below is an exclusive extract from chapter four of Living While Black. In this chapter, named “Black Bodies”, Kinouani links the historic mistreatment of Black people to contemporary, everyday acts of othering and considers the impact these acts can have on a Black person’s body.

Guilaine Kinouani’s Living While Black is published by Penguin Books and is out on June 3, 2021.

Excerpt from Living While Black by Guilaine Kinouani, exclusive to Bustle UK

Chapter 4: Black Bodies

You get into a room. It is a white space.

As you enter, you feel a sense of heaviness. You look around and notice pairs of eyes staring as though devouring you. You instantly realise you are the only person of colour in the space. A sort of malaise takes hold of you. You feel a little queasy. Perhaps the discomfort starts to make you feel dizzy. You may experience nausea. You might attempt to stick around and impose your presence, in silence. You may even take a seat but in any case, your body is reacting to some- thing. Soon enough that something becomes overwhelming. Every move you make is with microscopic precision as self-consciousness takes over your body. Your Blackness is in sharp closeup from the outside in. You know you want to exit now. You know this space is inhospitable to you. It may start to feel hard to breathe and so you try to look for a way out and a reason to leave, discreetly. You find one and you disappear almost as quickly as you entered. Your departure likely goes unnoticed. What happened in that room? What was your body reacting to? Is this only anxiety or have you been expelled from that space? Whose fantasy were you acting out?

This chapter centres on the Black body. The Black body as a site of violence, but also the Black body as site of contestation. The impact of racism often finds itself lodged in the Black body. So, in this chapter, in order to further our understanding of racial trauma on Black groups, we examine how Black bodies become permeated by whiteness. How they are transformed and shaped by white supremacy and the impact of racist violence, how even when psychological, affects our physical health. The above scenario illustrates how quickly and covertly we can be policed and consumed. How powerfully and yet invisibly we can be excluded. It is a painful reminder that in the white imagination there are still so few spaces we can rightfully claim as ours.

Furthermore, I have no doubt that to most Black readers, walking into a hostile white space will be known if not cognitively then through their body. Most of us have been taught to discount knowledge that we acquire through our body, our embodied experience of the world. Partly this is due to whiteness and its hyper-rational aspirations. Partly this is because as Black people we have been taught to replace our subjectivity or our experience of the world with that of those who do us harm. Partly this is a survival strategy, and intergenerational trauma too. So, we learn to be suspicious of our senses ourselves and ignore what our body tells us about the world, in the same way as, again, ancestral and indigenous traditions were erased through colonialism.’