28

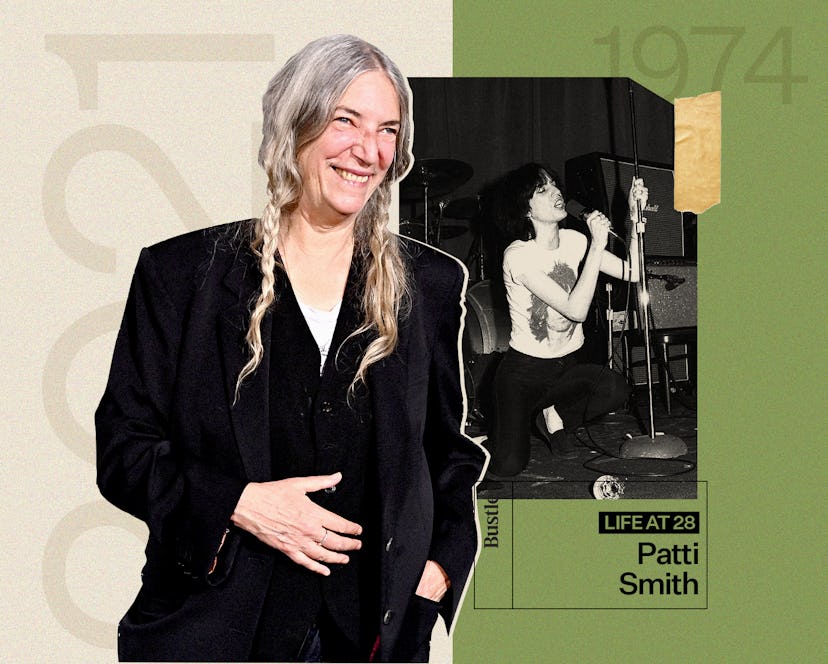

At 28, Patti Smith Smoked Pot, Ate Pizza & Wrote Poetry

She also put out her seminal album, Horses.

In Bustle’s Q&A series 28, successful women describe exactly what their lives looked like when they were 28 — what they wore, where they worked, what stressed them out most, and what, if anything, they would do differently. This time, Patti Smith reflects on the year she became a rock star.

Patti Smith doesn’t have too many regrets from when she was 28. There are, of course, a few: she wishes she spent more time with her mother; she had a self-proclaimed tendency to be “an asshole.” “My regrets are always similar. I [wish I] would have sometimes been less careless with people's feelings. I could be really thoughtless,” she tells Bustle. “But I always did the best work that I knew how. I wasn't a prodigy. I had to work hard to get to do anything that I did.”

Smith, now 74, works with the same vigor she did as a budding 20-something rockstar. She put out her latest memoir, Year of the Monkey, in 2019, and is already hard at work on her next book. And much like when she was 28, she’s still working on her flaws. Namely, trying to be more careful with others’ emotions. (The first five minutes of our call were, er, frosty, but by the end she shed light on her initial reticence, offered me writing advice, and took down my address to send me a book.) “Being a performer and the adrenaline and the stress of it can bring out aspects of your personality that you didn't even know you had,” she explains.

Smith spent a great deal of time reflecting on the creative evolution of her 20s — including her 28th year — for her National Book Award-winning memoir, Just Kids. The memoir is a romantic rumination on her early days in New York City with her former lover and friend, the late photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, as well the artistic milieu of ‘70s New York at large. Smith published the book in 2010, and while she’s grateful for its success, she’s now eager to focus on the future rather than her past. “What's important to me is what I'm writing now,” she says. “I am endlessly curious and endlessly engaged in, ‘What is the next thing? What is the next dimension? What is the next piece of work?’”

Still, she’s game to reflect on the past as a reference for her future. Below, Smith discusses the release of Horses, working in the Strand, and eating pizza in Tompkins Square Park.

Take me back to when you were 28, in 1974-1975.

My 28th year was a very fast-changing year. The release of Horses — which came out in November [1975] — was an extension of poetry that I had written as early as 1968, and the poetry had evolved through live performances. Then we wound up with a rock and roll band. I had no real sense of what that meant as a vocation. I was offered a record contract, so I thought that'd be nice. But I wasn't thinking about it in terms of what would happen next, the whole idea was to complete [the record]. I had no expectations. It was just about trying to do good work.

How did you celebrate the album’s release?

Horses garnered a lot of attention and a certain amount of critical acclaim, but it barely made the charts. We didn't have monetary success, but we could quit our jobs and we started getting tours. I was surprised at the amount of support that [the album] got publicly. A lot of people really liked it, but other people also hated it. I had death threats because of the first line of the record. [Ed note: the album begins with the lyrics, “Jesus died for somebody's sins but not mine.”] I had people saying that I was going to go to hell. But we were just happy to have a record.

I was also happy that people really loved the album cover. They loved Robert [Mapplethorpe]'s photograph. He took 12 pictures that day. He took one roll of film and on the eighth one he said, "I got it. That one has the magic." He was so supportive and I wanted people to see his work and see me through his eyes. So it was a great thing [that the art was recognized].

You write about that moment in your memoir, Just Kids. How has immortalizing that time of your life in writing altered your relationship to those memories?

I had no personal agenda with that book. What I wanted was to give people New York City at the time and my relationship with Robert. I might never have written it if he hadn't asked me to the day before he died. How could I say no? But I don't feel like there is anything I would have written differently. I might write a different book, but it was the book that Robert asked me to write.

[Actor] Sam Shepard read the book and I was a little worried. I said, "Well, what'd you think?" He said, "It's like it was." And to me, that said it all. Some people think it might be over-romanticized or [written] from whatever subjective point of view. Well, what isn't?

What did a typical Friday night look like for you at 28?

We didn't have a lot of money back then and I'm not the most social person, so I was probably hanging out with Robert. ‘75 was an interesting year because that year there was a lot of acceleration. Bob Dylan came to one of our earlier shows before we were signed — that generated a lot of press. I got to be friendly with him and he was very encouraging.

But I wasn't the kind of person who was like, "It's Friday night, time to go out." I was probably working at the Strand. Then I’d go to the East Village, have pizza, and hang out in Tompkins Square Park. I wasn't really a drug taker or a drinker. So I might have been smoking pot and writing poetry.

What types of things would you discuss over pizza and pot?

Robert [and I would] look at books or we'd both draw, because I drew and he would work on collages or whatever. Or else he would get some film and I'd just go over to his place and we'd take photographs or look at his new work. All my closest friends [have been] work-centric relationships, as well as emotional or any other kind of relationship. My friends at the time like Judy Linn would take photographs of me. But in terms of talking about stuff, I'm not very analytical. I just like working, reading, or looking at work.

Given that you worked at the Strand, what were you reading at the time?

I love French literature, so anything I could find. The Strand was a great place then because there wasn't any internet or these services that sell rare books, but you could find unbelievable books at the Strand. I remember buying almost anything that existed in English about [Arthur] Rimbaud [for only] $2, $5, 50 cents. I would say it was my French-Moroccan period, so that's pretty much what I was reading. And I was reading [William] Burroughs. I knew William and he would give me his books: Port of Saints or The Wild Boys.

Has there been a moment in your career when you felt like you truly made it?

There's been so many. My wedding day, having my children, when Just Kids got the National Book Award. When I first stepped into Paris with my sister in 1969. I mean, my life is filled with “you made it” [moments]. But I still have my sack and stick and I'm still moving toward the next thing I can make. We're very lucky as human beings that we get many opportunities to achieve something wonderful. Sometimes [those are] very personal and sometimes [they’re] for the whole world to see. I'm looking forward to seeing what the next thing will be.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.