Books

Hate Your Job? We've Got The Book For You

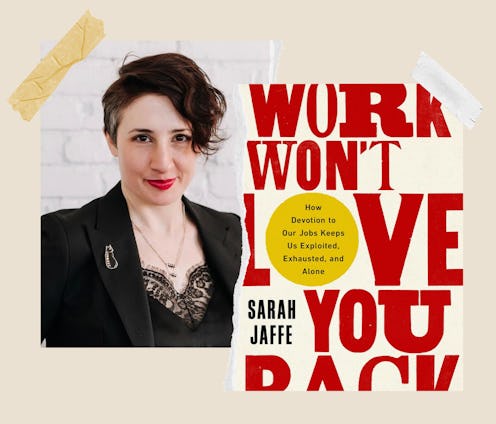

Labor reporter Sarah Jaffe explores the perils of the workforce in Work Won’t Love You Back.

Work sucks. Whether you're in a corporate job, a member of the gig economy, or a creative type, all jobs come with their own unique set of drawbacks. But reporter Sarah Jaffe's new book Work Won’t Love You Back posits the question: does it have to feel this bad? Nearly 75% of workers experience burnout, and women are more likely than men to feel its defining characteristics: mental and physical exhaustion, inefficiency, and cynicism. (And these numbers were from before the pandemic.)

Yet in spite of these harrowing statistics, the trendiest way to keep employees working is the myth that work is the thing we love. That our self-worth can be derived from logging long hours and going above and beyond with our tasks. Or as the cheerful clickbait advice puts it, “do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life.” And because of this, many of us never stop working, even as our passions and interests are funneled into performing tasks that benefit corporate bottom lines more than our personal growth.

Work Won't Love You Back follows 10 individuals across wildly different sectors, from a Team USA women's soccer player experiencing the wage gap, to an artist suffering depression because she’s stigmatized for not having “a real job," to a nanny leaving her own child so she could move into her employer’s home when coronavirus hit New York. The result is an incisive account of how capitalism convinced us to abandon our affections, bodies, and time to instead punch in and punch out.

Below, Jaffe reflects on the effect the pandemic has had on work culture, the power of unions, and stimulus checks.

What inspired you to examine the way that our culture values work?

I write about work because my experience at work sucked for a long time. I went to college to figure out "What am I going to do for the rest of my life that won’t make me want to die every day?" I wanted to be a novelist [or] a screenwriter, [then] after graduating with an English degree in a post-9/11 recession job market, I ended up waiting tables and working retail for five years.

When the 2008 recession happened, American middle-class jobs were disappearing even faster. The jobs replacing them were what I had done when I also couldn’t get a “career” job: service work. Meanwhile, the creative labor that you were lucky to get into was also starting to suck more. There were more freelance [writers], and the few full-timers were being paid $35,000 to live in New York City where your rent is [often] at least $1,000 with roommates. I wondered, what is the force bringing all of this together? Why has the expectation to love your job become more and more pervasive over the last few decades, despite worsening conditions? For labor coded as feminine, it’s a very old expectation. In other ways, it’s really new.

You open the book with a history of unpaid labor in the home, and use classic feminist theories to explain why “emotional labor” is underpaid and undervalued for all of us. Why are women still the backbone of the labor-of-love conversation?

Having babies means reproducing humans, which means reproducing a labor force, which means the ruling classes can continue to make a profit. That reproduction is done by women in the home, for free. Women were, and still are, seen as "natural" caregivers, where the work of cleaning, cooking, nursing are not "skills" but innate traits. Low-wage caring work today is not just done by women. It tends to be done by Black women and immigrants, people who are doubly naturalized as good at that work and therefore they don’t really need to get paid fairly for it. The love of a smiling baby or whatever is its own reward.

How are some workers fighting that narrative?

When teachers, for instance, go on strike, the first thing that gets said to them is always, "Don’t you care about the kids?" That’s why this new generation of teacher strikes has been really smart about framing their demands as also making things better for the kids. To say, "We strike because we care for our kids."

Suddenly people are considering who counts as essential workers, and asking why so-called “essential” work is the worst paid.

What was it like working on this book when the coronavirus pandemic hit and the conditions of work changed for everyone?

We’re in a great moment to talk about how much work sucks because we have mass unemployment [and now] everybody has to think about these questions in ways that nerds like me spend all of our time thinking about. Suddenly people are considering who counts as essential workers, and asking why so-called “essential” work is the worst paid.

Close to a million new people are filing for unemployment every week. What if we all worked less and we distributed the work more evenly so that instead of some people working 70 hours a week and a bunch of people who aren’t working at all, we actually had everybody working a four-day or three-day week? What if we distributed resources and time so that everybody could enjoy a decent standard of living and had more time to do things that they actually like to do? What if we had the freedom to discover what those things even are?

The point of hope that I found again and again throughout the book, from Toys ’R Us employees to video game developers, was the formation of unions. Why is that a common thread?

A union can give you the sense that you’re part of something bigger than yourself, and that’s the best thing that can happen to a workplace. [In] the chapter “Proletarian Professionals,” [we] talk about how in a hospital or a factory, everyone is working together towards a common goal because the management wants them that way. Whereas in the university, we can feel really isolated and pitted against each other. In journalism too, we’re all waiting to get to do that one feature story.

Solitary working conditions, even before coronavirus eliminated offices, made it hard to feel a connection with your coworkers. But when you do figure out ways to come together, it’s often the best thing about the job. I think solidarity is a very human need. I’ve talked to factory workers at GM, Carrier, and others who are losing their jobs due to the factories closing. If they’re going to miss anything about their job, it’s each other. They miss the union if they’re union activists; they miss their buddies and getting one over on the foreman with a prank.

In 2016, Trump promised to curb those factory closures, though he ultimately failed. His name doesn’t come up in your book as much as he could have. Was that a conscious effort on your part?

Most of the workers that I talked to are not looking for a solution by electing someone. Politics is made and done in the street and in the workplace and in the consciousness-raising group and in so many different places, and it eventually trickles out to elections.

That’s not to say that elected officials cannot do things. The pandemic has reminded us how much they can do. They can send $1,200 checks to everybody. Turns out we can [provide] a basic income because we’ve done it now.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.