Books

The Louder I Will Sing By Lee Lawrence Is A Story Of Generational Strength — EXCERPT

The writer and activist's memoir explores the devastating impact of police brutality on his family and the fight for change that has been his life's work.

Content Warning: This piece contains discussion of police brutality that may be triggering for some readers.

Author and campaigner Lee Lawrence grew up in Brixton, a place he describes as, “a rich community full of culture and spirit.” His parents' friends were aunties and uncles. When they say it takes a village to raise a child, that was his Brixton. However, on a Saturday morning, at 7 a.m. on Sept. 28, 1985 his life was changed forever when his mum, Dorothy “Cherry” Groce, was shot by the police in their home during a bungled raid.

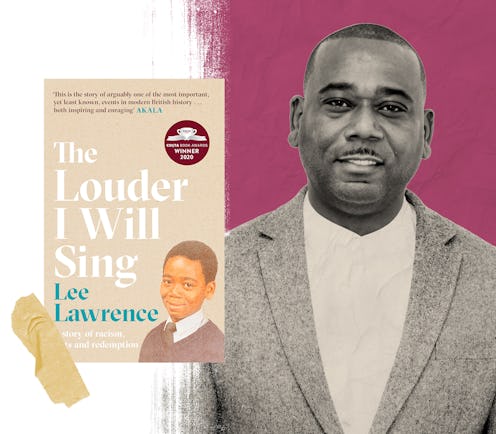

His story is the subject of The Louder I Will Sing which won the Costa 2020 Biography of the Year. Lawrence talks about his mum's attack, growing up as a young Black man and carer, and how the subsequent 35 years of his life have been shaped by what happened to his family. His fight for justice for his mum started in 1985 and he continues to push for change to this day.

Lawrence explains that although he was only 11 years old when his mum was shot, he recalls it “like it happened yesterday. It’s a scar that will never fully heal.” Lawrence was in bed when he heard a noise in his house. He saw his mum get up and was then himself startled out of bed by a loud bang. His mum was lying on the floor while a white police officer stood in the room with a gun, demanding Lawrence calm down.

She’d been shot and the bullet had shattered her spine. The author says he remembers her faintly saying, “I can’t breathe. I can’t feel my legs. I think I’m going to die.” In that moment Lawrence didn't know what had happened to his mum but he said that, after seeing the look on his dad's face, he knew he should be scared. His mum survived but was paralysed from the waist down.

Lawrence details how, after the news broke that his mum had been shot, and it was wrongly reported that she'd died from the shooting, a crowd gathered and wanted answers. The events were the beginning of the 1985 Brixton uprising. “A lack of understanding of this community is what led my mum being shot in the first place. And then how it was reported reinforced what people thought about the people that lived in this community,” he says, “bringing this story of a normal family makes what happened relatable. It allows people to reflect through different eyes.”

Lawrence has dedicated his life to social change. He was a a carer for his mum up until she died in 2011. Their experiences prompted him to create Mobility Transport, an organisation which works to increase access to accessible transport for disabled people. He's also used his experiences of police brutality to consult with the Metropolitan police to help improve community engagement, per the Guardian.

His inspirations for writing the book were two-fold. “I pay homage to my past; my mum, my greatest inspiration and hero. Also to the community that rose up for that injustice. They were heroes to do that,” he says, “I’m also inspired and continue to fight on for my children. I don’t want the residue of that trauma and injustice to live on in my children.”

Introduction by Alice Broster.

This extract is from Chapter 1 of The Louder I Will Sing, and takes place just after Cherry Groce died in 2011.

I was in the early days of grief, still coming to terms with the fact that Mum was no longer around. It was odd being in the hospital without her there; it felt that little bit different, that little bit emptier. I’d been so many times to visit Mum I knew the way to the ward by muscle memory. But this time, I headed in the opposite direction, downstairs, in search of a small office in the basement. I explained to the woman behind the desk who I was and what I needed. She gave me a small smile of sympathy and disappeared to look through the files. I waited. The fluorescent strip light hummed.

OK, she said, returning. Here you go. But she didn’t hand anything over. Instead, she continued to read. Then she whispered, more to herself than to me: Oh, hang on.

She looked up. She said: There’s a comment here. The doctor has written something. I’m sorry, but I can’t give you these at the moment. He thinks this might need to go to an inquest.

An inquest? I didn’t know what that was.

It looks like the doctor is asking for a post-mortem to be done, the woman explained. And then this will need to be referred to the coroner’s office to decide how to proceed. I’m sorry. These sorts of complications are probably the last thing you want.

She tilted her head to one side and gave me another sympathetic smile.

There was plenty I had wanted to happen in my life; this really wasn’t up there with them.

It turned out that my mum’s doctor wasn’t certain about what the cause of death was. Or rather, he was clear on the medical reasons why Mum died, but wasn’t completely certain about what had caused them. The post-mortem was done by a forensic pathologist called Dr Robert Chapman and took place a couple of weeks later. When I got sent the findings, I read it at my kitchen table in fits and starts; a paragraph or two, then flicking forward desperately, hoping that my brain would soak all the information up without me having to properly digest it. Mums aren’t bodies to be dissected. As part of the process, the pathologist removed a section of her spine to take away and analyse. As far as I know, that’s still in a lab somewhere, gathering dust on a white shelf.

Reading the report was hard going. Chapman described how he found a succession of metallic fragments lodged in my mum’s spine. These were fragments from the bullet fired by DS Lovelock back in 1985, which had become embedded. That wasn’t a surprise: from the start, the medical advice when Mum had gone to hospital was that it was simply too dangerous to try and remove them all – any attempt to do so could cause further damage. The doctors took out what they could. The fragments that remained caused my mum pain throughout the rest of her life. A recurring, sharp, stabbing reminder of what had happened one September morning.

But what was a surprise was Chapman’s conclusion. It was those fragments, he said, that killed her. It was those fragments that had caused her paralysis and paraplegia, and it was the paralysis and paraplegia that caused a urinary tract infection and bronchial pneumonia, and it had been the urinary tract infection and bronchial pneumonia that had caused more infection and acute renal failure that was the last straw. I had it in my hands: incontrovertible proof that, over two and a half decades after my mum had been shot by a policeman, his bullet had resulted in the end of her life. The pent up need for action sat in my throat like a stone that was on fire.

He thinks it might have to go to an inquest, the woman in the hospital basement had said.

I didn’t know how an inquest worked or what it could do, but I knew that I wanted it. The first Brixton uprising in 1981, the murder of Stephen Lawrence in 1993 – they’d both resulted in public inquiries. After my mum had been shot, there had been an internal police investigation, which led to charges being brought against the officer who fired the gun. But he’d been found not guilty, and no public inquiry had followed. Public inquiries have a habit of asking awkward questions that authority figures don’t want to find themselves answering. As a family, we’d never had a chance to find out what really happened that morning all our lives were turned upside down. Would the inquest give us an opportunity to do so?