Life

Abby Norman Knows Women Shouldn't Have To Pretend They're Not In Pain — So She Stopped Pretending

When you suffer from chronic pain, it's easy to feel alone. I felt extremely isolated before, during, and after my endometriosis diagnosis. Why was my "period pain" so abnormal? Why was my pain so easily dismissible? What was wrong with me? I didn't find very many answers to these questions... until I came across Abby Norman's work.

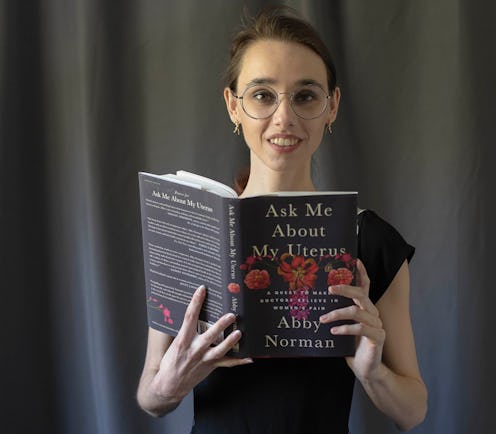

Abby Norman is a writer, advocate, and avid X-Files aficionado. She also suffers from endometriosis, and while the disease is not the only thing that defines Norman's life, it is the subject of her debut book Ask Me About My Uterus: A Quest to Make Doctors Believe in Women's Pain. Ahead, Norman — who is one of Bustle's 2018 Rule Breakers — talks about finding the strength to share so much personal information about her health, breaking rules in order to be a better advocate for herself and others, and how she combats imposter syndrome in her life and her career.

Danielle Campoamor: I want to start with something we've talked about before. Socially, and especially as women, we're told we're not supposed to complain or talk about pain. What made you decide to break this rule and write an entire book about the pain that you live with?

Abby Norman: I've always been that girl who said the thing that everybody was thinking but didn't wanna say. That's just how I am. Although, in terms of the vulnerability that comes along with that, I had to really push myself. Even now that I've done it, I'm still like, "Wow, I did that."

I knew what would have helped me when I was first trying to wrap my mind around my experience would be going to the library or bookstore and finding something to put it into context.

DC: You really have given up so much of your private life. Could you give us insight into pushing past that vulnerability?

AN: I tend to have an all-or-nothing kind of perspective. It's been helpful in guiding me through this process. If you can't go the whole way, don't do it.

Deep down, I did not think the book was gonna take off like this. I knew that people would relate to it in private. I did not think that it was gonna get all the press it got. I didn't think that the people who blurbed it would blurb it. I didn't think that I'd still be getting message after message after message from people who want to engage with me.

It's not because I didn't think it was an important conversation. I just didn't think I had any power that way. If I'd known it was going to be like this, I probably would have gotten way too intimidated.

I feel like there's also a pressure in identifying with having a disability ... people expecting you to perform it or to prove it in some way.

DC: You've given so much of yourself and you're so transparent with your medical condition and the pain you've experienced. ... How do you take care of yourself?

AN: I'm going through this right now. I'm trying to figure out how much I'm comfortable with [when it comes to] social media. One of my mentors said to me, "I just don't understand why you're willing to put all over the internet how shitty you look and how bad things are," and I was like, "I don't have the energy to act like it isn't this way." I don't wanna gloss over the reality.

Every once in a while, I'll get this really lovely note from somebody — usually from women a little younger than I am — who have figured things out sooner than I did. Their parents took care of them after they had surgery and they got to go back to school and they got to take up dance again. ... Or they got a boyfriend or they went to Paris. ... And there's a part of me that's like, "Oh wow, this is great." But then I'll be like, "Why do I also feel sad for myself?"

DC: It would be hard not to feel like that's just unfair.

AN: This is so confusing for me because I know I helped [them], and they are so grateful and they're telling me these wonderful things and I'm happy for them, but also I'm really mad because I'm in so much pain and I can't eat solid food. And then I feel so guilty because I feel bad about that.

I think I have to take a step back and say, "What do I need?" I've always said that the book will be able to do more than I can, and that was one of my big reasons for taking a leap. I knew that I would never physically be able to do as much of the work as I want to, and that the book was the solution to that, because it was tangible and it could go to these places.

I feel like there's also a pressure in identifying with having a disability ... people expecting you to perform it or to prove it in some way. I don't think I figured it out yet. I've only just realized that I need to start figuring it out and it's gonna come down to how much time I'm on social media. I'm also hoping that I can stabilize in terms of my health so I'll be able to take advantage of the life I have here.

So that's my priority: trying to balance that against the responsibility I feel to advocate all the time, and the responsibility I feel to be present and relevant, all the time.

I've always been very bad at doing nothing, and one of the things that being so physically weak has forced me to do is reckon with this sort of stasis. There are literally times when I physically can't force myself to do something and that has forced this emotional and intellectual calm.

DC: Who's your rule-breaking icon?

AN: Dana Scully. She, like me, was never a rule breaker to be a rule breaker. Growing up, I was such a rule follower all the time. But, if I was on the playground and thought there was some injustice, I would muster up the little integrity of a 7-year-old and be like, "I'm going to challenge this, and here's why."

Then Scully flew into my life and became my ultimate role model — a fictional character. She was very willing to challenge a rule not just if it threatened her own goal or her own self, but usually because it was hurting somebody else.

I knew when I wrote this book that it wasn't going to change things for me. The path I'm on is set. So when I see that this book has in some way made someone's story different, it's powerful.

I've understood from a very young age what it means to use your situation in life to be aware of other people's — and to do whatever you can to help them.

DC: What is one rule that you think people should break more in this community?

AN: The broader chronic illness community is really good at being aware of other people's needs and sensitivities. I think where that goes wrong, though, is being really good at taking care of each other at the expense of taking care of themselves.

People will look at their disease or disability community and say, "This person is worse off than I am. So I don't want to ask for help because this person needs it more than I do."

Sometimes people do that to such an extreme that they completely lose sight of their own needs. There's this idea that there's not enough to go around — there isn't enough goodness, there isn't enough selflessness, there isn't enough kindness. We're all too afraid to admit we need it, and we're all trying to be really stoic because we just feel like the world is such a hard place to live in. But that's totally counter-intuitive.

DC: You've been very open about your privilege. You did such a beautiful job in the book of elevating the experiences of others who often don't get talked about in the endo or the chronic illness community.

AN: I couldn't write the book without doing that. I didn't want the book to make a space for me. I wanted the book to make a space for anybody else who felt like they needed a space to have this conversation.

When people criticize the book, in terms of its structure or its narrative or the choices I made as a writer, they continuously criticize its detached nature when I talk about my personal life. But part of that was deliberate because I wanted people to feel like they could use my words as their words.

I've understood from a very young age what it means to use your situation in life to be aware of other people's — and to do whatever you can to help them. It made acknowledging my privilege and constantly reevaluating it a personal thing.

I get really frustrated with it. But I'm aware that as hard as it might be for me to constantly reevaluate, it's never going to be as hard as it is for the people who are actually living in these communities where they are experiencing this level of oppression and this level of conflict.

There's a balance of understanding the places where I have privilege that I can leverage to help elevate other people, and also being aware of how I'm still disadvantaged in some ways, but not letting that be an excuse for not doing something with the privilege I do have.

DC: Wow.

AN: It's a really tough balance.

DC: What's one thing you've given up to do the work you've done? In one word?

AN: I might need to look at a thesaurus.

DC: This makes me so happy.

AN: What I wanted to say was "innocence."

DC: And in one word, what's one thing you've gained by doing the work you've done?

AN: Community.

DC: Do you have a rule breaker motto?

AN: I've said it a million times and I'm going to say it forever, but it's this quote by Mary Oliver: "Instructions for living a life: Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it."

DC: Oh, I love that.

AN: Are you fully present and paying attention to the world around you? Are you taking things in, in a way that allows you to be moved?

[S]uccess is not a solve. Success in one area of your life does not mean that other things are not going to fall to shit.

DC: I want to end this with something universal. When a lot of the readers read about the incredible work you've done, they're going to kind of feel imposter syndrome. Do you ever feel it?

AN: Every day of my life. I'm constantly worried about that. Even though I'm a writer whose book was reviewed in the New York Times twice, I still look at my resume and I'm like, "Oh, should I say that I'm an author? Should I say that I'm a writer? Am I writer?"

I wrote a book. I literally wrote a book. I have a stack of them right there. They're in bookstores. People send me pictures of them in bookstores all the time.

DC: How do you push past it?

AN: I just take a step back and put it into a less emotional perspective because the reason I get that feeling is not based on logic.

There have been times in my life, like in high school, when I had maybe written some poetry and had a lot of fanfiction on the computer. ... If you had asked me if I was a writer, I'd have been like, "Yes I'm a writer."

I was so convinced. I was so confident. But how can I possibly intellectually justify feeling less like a writer now, than I did when my claim to fame was a 60,000 word X-Files fanfic?

I've always said, success is not a solve. Success in one area of your life does not mean that other things are not going to fall to shit. You just have to be able to balance that. And the same way that success doesn't solve all those problems, those problems don't negate your success.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.