Books

'The Disaster Artist' Was A Book Before It Was a Movie - And It's Actually Deeply Moving

It's not an exaggeration to say that the premiere of James Franco’s movie The Disaster Artist is the single thing I've most looked forward to in 2017. It has little to do with the post-film festival buzz, the rave reviews, or the all-star cast. It's because the 2013 book on which the movie is based is one of the most hilarious, surprising, and human stories I've ever read.

The Disaster Artist: My Life Inside The Room, The Greatest Bad Movie Ever Made is Greg Sestero’s memoir about acting in a film that has been called "the Citizen Kane of bad movies." The movie’s plot, perforated as it is, follows all-around good guy Johnny and his "future wife" Lisa, who cheats on him with his best friend, Mark. Also, there’s a rooftop fight with a drug dealer, a conversation in which Lisa’s mother frankly and suddenly states that she “definitely has breast cancer,” and many extremely long, extremely un-sexy sex scenes. Dialogue bears only the slightest resemblance to real human conversation, and many shots are out of focus. As Sestero, who begrudgingly played Mark, describes The Room in the book, “it is, essentially, one gigantic plot hole."

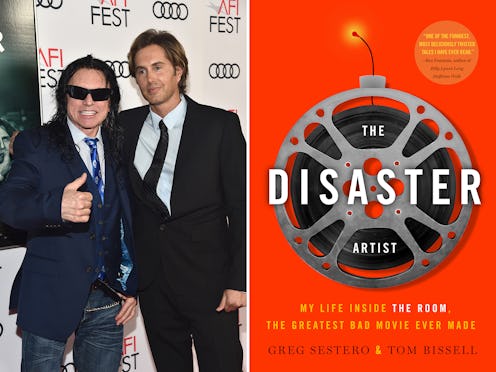

The writer, director, producer, and lead actor of this monstrosity is Tommy Wiseau, a vampiric man of indeterminate age and provenance, who funded the $6 million production himself, with a fortune just as mysterious in origin.

The Room now enjoys cult fandom and midnight screenings around the world with Rocky Horror-esque audience participation, and to put it simply, it's so bad it’s good… and then circles back around to being bad again.

But to truly comprehend why The Room matters to the culture, and to the people who made it, that’s where The Disaster Artist comes in. It depicts, among other things, how Wiseau was rejected by the Hollywood establishment and decided to make his own movie, with a singular vision and absolutely no compromise. He created something that has affected and inspired people for nearly 15 years, and in the process, became a legend like his idol Marlon Brando. He just did it in all the wrong ways.

“It is, I hope, a tale of heart, sadness, and blind artistic courage,” Sestero writes in the author’s note. “The story it tells is as much about the power of believing in oneself as it is about the perils that can arise in conquering self-imposed limitations.”

The Disaster Artist by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell, $8, Amazon

The Disaster Artist is co-written with acclaimed author Tom Bissell, a master of narrative non-fiction whose own relationship to The Room seems destined. Shortly after moving to Portland, he came across the Wikipedia listing for the film. Astonished by what he was reading, he decided he had to see the movie, which turned out to be premiering that night five blocks from his apartment. “After that experience, I knew right away I had to write about the movie. Harper's published the piece, Greg got in touch with me, and the rest is history,” Bissell tells Bustle. “It just goes to show you the degree to which sheer luck and caprice rule the course of anyone's life.”

The Disaster Artist book answers the big questions about The Room — how it came to be made in the first place (a combination of Wiseau’s inexplicable wealth and sheer doggedness), why anyone was associated with it (misguided trust in Wiseau, a driving desire to be an artist, and also, the need for a paycheck), and what they really thought while filming (a similar appalled incredulity that viewers feel now). The book is hysterical and bizarre and delivers all of the behind-the-scenes fan service that Roomies want. But what makes it incredible is how universal it is. The Disaster Artist is really many books in one. An actor’s memoir. An underdog story. An insider look at moviemaking. A biography of an incomparable auteur. A heartbreaking narrative of an immigrant and his quest for the ungraspable American Dream. An artistic mission statement. But more than anything, it’s a chronicle of a fraught but ultimately unshakeable friendship.

“When I was working on the book, and telling people about it, I would often mention how much of it was about these two guys getting to know each other in the late 1990s,” Bissell says. “And everyone of course said, ‘That sounds terrible. Why not just stick to The Room stuff?’ No one knew the material Greg was sitting on. How rich and funny and sad it was. I told Greg early on, ‘The great thing about this is that everyone thinks they're here for the making of The Room, but what's actually more interesting is your friendship.’”

At 19, Sestero met Wiseau in a San Francisco acting class. Sestero was the all-American kid Wiseau wanted to be, or barring that, impress. Wiseau was undeniably odd but also fearless and supportive, two things Sestero craved as a young actor. Despite Wiseau’s weird habits (shouting in restaurants, drinking exclusively piping hot water) and secrecy about his personal life, they became close friends and eventually roommates in LA. On and off the set of The Room, Sestero functioned as Wiseau’s babysitter and translator. He may be the only person who has come close to understanding Wiseau, ever.

It’s heartening to read that much of their relationship was commonplace, even if one of them was one of the most unique people in history. They took road trips and talked about girls, made each other laugh, and shared an obsession with James Dean and becoming movie stars. But over the years Wiseau became increasingly manipulative and competitive. He felt threatened by Sestero’s success (the lead role in Retro Puppet Master), his other friends, his girlfriend, and his very existence as the attractive American guy Wiseau always envied.

Told in chapters alternating between The Room’s production and the duo’s early friendship, the book’s portrayal of Wiseau is honest, which means balancing his many contradictions.

“We realized we could sort of allow those sections to talk to each other, so that when Tommy is at his most sympathetic and kind in one storyline, we come back to him being a screaming tyrant in the other storyline,” Bissell says.

Throughout, Wiseau is shown as an intrepid filmmaker, a downtrodden outsider, and a toxic friend, the hero and villain of his own story. It’s a portrait of a man whose real identity lies somewhere between zany artist and sociopath (Sestero was shocked to see similarities to their friendship when he watched The Talented Mr. Ripley). The book also attempts to piece together Wiseau’s possible history from what he has told Sestero, including his dark childhood in Communist Europe and his entrepreneurial beginnings selling yo-yos at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. The authors aren’t sure if these stories are accurate or even plausible, but it lends an extra layer to how we understand Wiseau’s personality—his character’s motivation, as it were.

“Tommy's view of the book, I think, is pretty ambivalent, which I get,” Bissell says. “But his reaction to the film has been hugely positive, as far as I know. Which is kind of weird.”

The film streamlines these complications slightly, as films are wont to do, which may be why Wiseau prefers it. But as movie adaptations go, it follows the book closely, with all of the verve and pathos the authors imbued. Bissell adores it.

“I love that they retained the love and big-heartedness that we tried to place at the center of the book, even though things get pretty dark from time to time,” he says. “We wanted to write a love letter to the so-called losers of Hollywood, and the screenwriters James and Mike Weber and Scott Neustadter wanted to do the same thing. So we were all on the same wavelength there. That's rare.”

The film, for its part, is excellent, and fascinatingly meta — a movie about the making of a movie. James Franco, like Wiseau, is simultaneously director, producer, and star. And the genius decision for Dave Franco to play Sestero highlights the offbeat brotherhood between the two men, and the desire of each to be the other.

James Franco recognizes that The Disaster Artist is essentially a road map for living an undaunted creative life. In the introduction to the recent movie tie-in edition of the book, he writes, “The book turns Tommy’s sometimes ridiculous struggle into a paradigm for those wishing to be creative in a world where it is usually too hard to be… In so many ways, Tommy c’est moi.”

But recognizing Wiseau in oneself isn’t always positive.

“I'm on a project right now that involves a lot of other people, and I was having a change forced upon me that I really didn't want to do,” Bissell says. “So yesterday, I proceeded to argue over email with multiple people throughout the day about why I didn't want to do it. I got really mad and unpleasant, I'm sure. And this is not how I usually am! At some point, I asked a friend on the project if I was being a Tommy. He said, ‘Maybe.’ So I stopped.”