News

Black Women Have Always Been Resisting

A new exhibition highlights how African American female artists were a driving force within the art world at the height of the Civil Rights movement. The Brooklyn Museum's We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-1985 explores how these women affected change back then—and offers critical tools for feminist advocates in 2017

The show, which was created to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the Elizabeth A Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, is also intended to illustrate parallels between the major political issues of that period and those of today.

Catherine Morris, who curated the exhibit, tells Bustle that she hopes contemporary museum visitors "will understand that the battles many of us feel we are fighting today have deep roots in our culture and we need to know that, and in knowing it we can better form strategies for our current struggles."

The work and activists featured in We Wanted a Revolution, accordingly, contain valuable lessons for modern resistance. A common criticism of modern feminism, for example, is that it focuses too narrowly on wealthy, white women, leaving other women (and their unique experiences) left out.

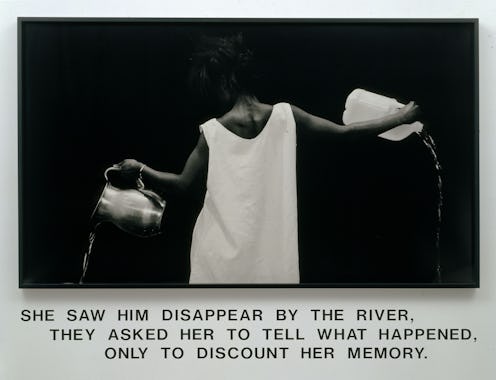

Lorraine O'Grady, a performance artist featured in the exhibit, addressed this issue in her 1982 piece "Rivers, First Draft," in which a black heroine is rejected by groups of white women and black men, before ultimately finding peace with herself. Carrie Mae Weems, whose "Ain't Jokin'" photo series is also featured in the exhibit, deals with the role of white beauty standards in propagating internalized racism.

"The politics and social priorities of a time, a place, a community, and the individuals who produce art are almost always immediately reflected in the work that is made."

"Black feminists were also much more prescient, through their own lived experience, about what we would today call intersectionality," Morris tells Bustle. "That is, the idea that no person is embodied by a single 'issue,' whether that be race, gender, sexual identity, class, or ability/disability, so these women were operating in a much more complex (in addition to harsh) world that demanded more nuanced and pragmatic approaches to dealing simultaneously with multiples forms of personal injustice."

The exhibition also illustrates the importance of taking political action in one's own industry.

In a second O'Grady performance piece, "Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire," the artist crashed gallery openings wearing an elaborate gown made of white gloves. (The gown is on display as part of the exhibit.) At each gallery, she cracked a whip and shouted criticism at the "timid black artists and thoughtless white institutions" who were present. The performance was an explicit challenge to end the racist and sexist exclusivity that permeated her industry.

Even for non-artists, examining resistance art of the past can be a useful way to learn about prior activist movements. "I think art is one of the most profound and timely measures of current thinking in any movement," Morris says. "The politics and social priorities of a time, a place, a community, and the individuals who produce art are almost always immediately reflected in the work that is made."

The art featured in We Wanted a Revolution portrays the stories of women struggling for respect and recognition amid an industry and a culture unlikely to give it. These women's incisive critiques of their own time inform our understanding of how to continue the fight for equality going forward.