News

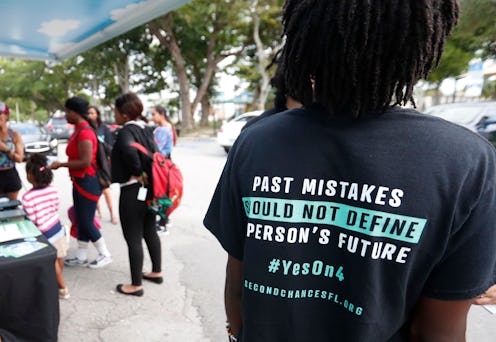

Florida’s Amendment 4 Gave America A Blueprint For Challenging Mass Incarceration

In this op-ed, Nicole D. Porter, the director of advocacy at The Sentencing Project, explains what the passage of Florida's Amendment 4 really means — and what's next for the rest of America.

There’s a long history of using the criminal justice system as a system of oppression in the United States. From slavery to the long period of extrajudicial killings, through lynching to the era of mass incarceration, the tendency of the United States has been to replace one system of oppression with another. Oftentimes, the systems of oppression have centered on how to socially control and respond to blackness, which means the approval of Amendment 4 in Florida is a significant victory.

As the director of advocacy at The Sentencing Project, a national research and advocacy organization based in Washington D.C., I’ve worked for many years with advocates in Florida on enfranchising residents there with a felony conviction. Florida was one of four states to have a lifetime voting ban for people with felony convictions, including people who had completed their felony prison probation or parole sentence. With exclusions for people convicted of murder and sex offenses, Amendment 4 automatically gives residents who have completed their felony prison probation or parole sentence the right to register to vote.

Florida accounts for more than a quarter of the folks disenfranchised. Nationally, there are more than 6 million who are disenfranchised from voting, so this change is significant. There has to be a formal process to change Florida's constitution, which will take place in January 2019. Once that happens and the policy is official, by our estimates, up to 1.4 million Floridians who were disenfranchised before this most recent election will now be eligible to register to vote.

There's a mix of reasons why so many people in Florida had a felony conviction that disenfranchised them for life. Since the early '80s, the nation's rate of incarceration has grown, the chance for U.S. residents to come in contact with the police has increased. Once residents come in contact with the police, there is an increased likelihood of getting charged with a crime and, once charged, a strong likelihood of going to prison, where prison sentences have gotten longer. Because of the increase in incarceration, the number of persons experiencing collateral consequences increased, too.

What's Next?

The fact that this happened by ballot referendum and with grassroots infrastructure should provide momentum and enthusiasm for activists in other parts of the country to organize similar efforts.

Governors can issue executive orders to re-enfranchise voters — like when Gov. Andrew Cuomo in New York issued an executive order authorizing voting for residents on parole in that state, expanding franchise to 35,000 residents. Successors to the governorship can rescind the executive order, re-instituting voting bans, which happened in Iowa, but targeting the governor to improve voting rights is always something that residents should consider. The grassroots conversations within states need to study all of the tools in the toolbox in order to move the conversation forward on expanding the franchise and addressing mass incarceration in general.

There could be a federal option. There is current federal legislation, the Democracy Restoration Act, which would authorize voting in federal elections for anyone with a previous felony conviction within the community. But it’s challenging in today's political environment, so what’s next is for state campaigns to expand the franchise to people who are living in the community on felony probation and parole.

We need to use the momentum to challenge mass incarceration. This movement should center the question: What is the fundamental purpose for excluding justice-involved residents from their civil rights? The momentum can continue to chip away at this system that has marginalized and disenfranchised so many people for so many years.

In some ways, the entire history of the United States has been around the essential question of what is the right of the black resident when it comes to being a citizen and when it comes to being a full community member. Felony disenfranchisement has been used as a proxy for blackness as a way to diminish and minimize citizens' civil and human rights.

It was a substantial victory for Amendment 4 to be approved. But there are a range of other collateral consequences and other efforts to address mass incarceration that activists can organize around now. Florida will hopefully provide a window into what might be possible to improve efforts to challenge mass incarceration.

As told to Celia Darrough.