Books

Millennial Readers Love This 69-Year-Old Poet — And Their Instagram Account

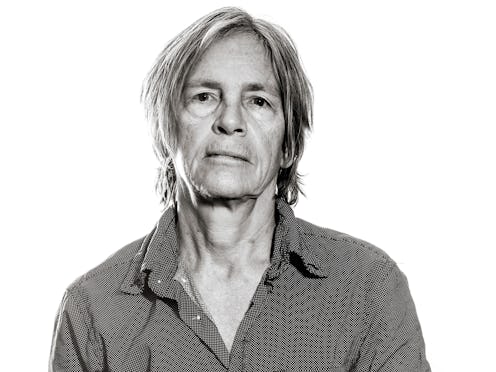

I’m in a workshop room in a London arts center. Forty people, mostly in their twenties, are whispering and giggling in anticipation of the arrival of a celebrity poet. We’re not waiting for Rupi Kaur, though. It’s Eileen Myles who will be leading today’s "radical write-in" — two hours of writing in complete silence. Wearing jeans, a checkered shirt, and Nikes, 69-year-old Myles opens a laptop while we take out our notebooks. The writing session has begun. After 30 minutes of scribbling, I glance at the notes of the woman next to me. "Eileen brought a laptop, are they just typing emails?!" it says. To me, it seems an indignant ask, though admittedly and unoriginally, my notebook contains the same question.

The laptop shouldn’t have come as a surprise, though. The cover of Myles’ most recent poetry collection Evolution is an Instagram picture (Myles has 25.2k followers on the platform and their Instagram pictures have been exhibited in New York), and the author’s photo on the back is a bathroom selfie. Myles finds that technology and social media have opened new channels for their poetry. "Writing a poem, composing a tweet, or adding a caption to an Instagram photo, all feel like one and the same gesture," they tell me at the coffee shop where we met before the writing session. "I see poetry as capturing what is happening around me and social media simply offer more options for doing the same thing."

Myles shuns binary thinking in writing and in life, and refuses to choose between print and screen, fiction and nonfiction, highbrow and nonchalant, he and she. This ambiguity makes it hard to define their work; the best introduction to Eileen Myles is still Eileen Myles. Luckily for us, they have created 20 books of poetry, fiction, and art criticism.

Myles has been on the literary scene for four decades and has received countless awards — including four Lambda Awards for books with LGBTQ+ themes — yet their writing feels remarkably fresh: Their poetry has the power to make you fall in love with New York for the umpteenth time and to experience the thrill of reading a literary lesbian love scene for the first time. As cliché as it may sound, reading Myles is like reading a good friend, at least for me. Their style is as honest as it is informal: "If the end of one's youth is a thin slice of cheese I ate mine standing in that room," they wrote in the novel Chelsea Girls. "I was there because I was hungry. That's all."

Yet their popularity — Chelsea Girls was reissued four years ago, Lena Dunham has cited them as a source of inspiration, and The New York Times called Myles "one of the essential voices of American poetry" in 2015 — is a fairly recent phenomenon, in part spurred by television show Transparent, which modeled a character after Myles. But there’s more to their appeal than television stardom. Maybe Vice was right in writing that “Eileen Myles has always been cooler than you” – and the world has only now begun to catch up.

Take Myles’ write-in campaign for president of the United States in 1991, which later inspired Zoe Leonard’s famous "I want a dyke for president" poem. Myles, just over 40 years old at the time, was the only openly queer candidate, the only artist, and the only one earning less than $50,000 a year. “It wasn’t until Hillary Clinton lost the elections in 2016 that I realized how progressive my mock campaign in the ‘90s was; how impossible it still is to elect a woman as president of the U.S.A.,” Myles tells me.

"Allen Ginsberg lived in the street where I found my first apartment. I’d often bump into Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol. There was something defining about them being part of the grid."

In their essay "Acceptance Speech," published in 2019 in Evolution, Myles hints at what their presidency might have been like, promising to make food and education free and to confine weapons to museums. Funny in a sad way, "Acceptance Speech" makes you long for a presidency that never was. “In both my presidential campaign and in 'Acceptance Speech,' I play with a sort of ludicrousness," they say. "But let’s face it – the nightmare of the moment we are living in right now was equally unthinkable a few years ago. Yet here we are, in the middle of it.”

Myles has a history of dealing with the seemingly impossible. At the age of 24, they traded Boston, where they grew up in a Catholic working class family, for New York City, where they hoped to become a poet. "I didn’t know any artists in Boston. It didn’t seem like anybody was in the thing they were aspiring to; they were on their way. In New York, people were there," they say. "Allen Ginsberg lived in the street where I found my first apartment. I’d often bump into Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol. There was something defining about them being part of the grid. Even the language would reflect that when somebody older might say: 'So Eileen, when did you come on the scene?' There was this sense of locality that was really important and you wanted to put yourself close to that."

To pay their rent, Myles took on an array of often physically demanding jobs: They were the personal assistant to the poet Jimmy Schuyler, and a foot and bike messenger. "I messed up my knees as a bike messenger, but that was part of the aesthetics of that time — the pilgrimage of the writer was experiential. Today a poet’s bio will mention their awards, where they live, whether they have a partner. And if they’re really crazy, they’ll mention their dog," says Myles, who has a page on their website devoted to their pets. "But back then it would say: 'The author is a fisherman and waitress, has worked in Alaska.' Those experiences mattered. That was the poet’s bio. That type of bio is making a comeback now, perhaps because skyrocketing rents force young artists to stack jobs as I did back then."

Those early years in New York are chronicled in Myles’ novels Chelsea Girls and Inferno, both of which convey an almost feverish urge to create. "Nobody ever told me how to live; they told me what not to do. In all these books about the lives of artists that I read [...] they took the simple beliefs in art and freedom and carried them to outrageous lengths. I could do that," Myles resolutely wrote in Inferno. Reading their poems, you get a sense that you can, too. When I scan the room during the radical write-in, I realize that this is part of Myles’ millennial appeal.

"I am experiencing what I call my 'Later Parade,' an expression I got from a Cat Power song."

In an interview from 2015, the year Chelsea Girls was reissued, Myles nuanced the idea that they shot to fame out of the margins. "People can’t let go of the unit of the poet or the unit of the privacy of their own reception, and that’s the thing that’s weird— the way I keep hearing about all these unknown years in the darkness I had with independent small presses, but no, that’s how poetry is known. It’s like forever — it’s many, many little rooms making a big room. That’s the nature of the art form, and that’s what’s happening for me now. It’s just the little room got big," they said. Perhaps the best way to put it is that Myles was already known to and loved by many readers, but in recent years their fame has extended far beyond poetry audiences — and the room certainly continued to get bigger since 2015.

"I am experiencing what I call my 'Later Parade,' an expression I got from a Cat Power song," Myles says. "Younger authors like Maggie Nelson, Ben Lerner, and Sheila Heti seem to see me as a funkier map maker, recommending my work to their own readers. And so my work has spread in an analogous way. I never played a musical instrument, but I always wanted the lifestyle of a musician and have led that life to some extent."

"A poem is very much like a good joke. Both operate on surprise and empty the space out momentarily; it leaves you in a kind of shock."

And so Myles did a lot of touring, accepting any invite to perform their poems. Today, they say they try to be more selective as to not become a cliché. "I am from a generation where lots of people died of AIDS, drugs, and alcohol; plenty of people who hit it hard and didn’t make it to their 30s. Now people my age are dying of ordinary things," they say. "When my mother died two years ago, I realized that I needed to make more time for myself, to make the books that I want to make. I’m also starting to cite death in my work in a different way. I don’t want to be creepy, but I want it to be in the room in the way that it is in my head."

In their new collection Evolution, such poems about heavier themes appear alongside more lighthearted ones, such as The Baby, which Myles jokingly refers to as "the best poem I ever wrote":

"The baby

says to the old

man let’s

have a cup

of coffee

the old

man says now

you’re talking."

Myles admits they take a special delight in short, silly poems. "A poem is very much like a good joke. Both operate on surprise and empty the space out momentarily; it leaves you in a kind of shock. Compiling a poetry collection is like choosing an outfit," they say. "Imagine that you’d still own all the clothing you ever had — it would be the most fantastic thrift store. Sometimes I throw out garments because they no longer match who I want to be, and two years later I think: 'That was a great shirt, I wish I still had it.' Poems can be retrieved — time is immediately dated in your work, but a poem can feel relevant again years later. While compiling Evolution, I went through my notebooks of the last 11 years and chose the unpublished poems that I wanted to put on my body again."

Myles went from being an outsider to signing with established publishers, pushing the boundaries of the literary world in the process. While imperfection in visual art, for example in the form of blurry Instagram filters, is trendy, language remains the most conservative institution in the world. Myles says. "In my twenties, I read the book Lectures in America by Gertrude Stein. Stein says she doesn’t use question marks and commas because if you need them, you’ve not built the sentence well. The sentence should be asking that question, not the question mark. So I use commas infrequently and only employ question marks for pop value. Editors still try to fix my punctuation, but these days I can refuse corrections and create a different sense of what one can be doing. Why should we all strive to write white middle-class English? Destandardization should be part of the blur and the shakiness of the times. Gertrude Stein said that language changes from the underclass up – right from the beginning of my career, I decided that I would be one of those changemakers."

And so during the radical write-in, I cross out my note about Myles’ laptop. Instead I ask myself: Why do I still seem to believe that poetry must be written on paper?

This article was originally published on