Books

The Life Lesson I Learned From Russian Poet Anna Akhmatova

I first discovered Anna Akhmatova’s poetry when I was living in St. Petersburg in 1994. It was a happy year, for the most part. But there were many times when I was confronted by the realities of the lives of Russian friends and had to dig deep to find any sense of optimism. Generally speaking, the people around me had very little money and not always that much food. If they had work, it was precarious. If you opened someone’s fridge, it would be virtually bare. It was very common for friends to ask me to lend them five dollars to last them to the end of the month. (They would almost always return it. Almost always.) Overall, life could be wearing. I frequently felt guilty and helpless. At the end of that year when I returned home to England to my parents’ house, without thinking I went to get some milk to make tea. When I opened the fridge, I was so shocked at the sight of the packed shelves that I burst into tears.

The one thing that always made me feel better was reading Anna Akhmatova. She’s not an obvious candidate for someone to cheer you up. Few writers have catalogued misery in such forensic, lyrical detail. Akhmatova’s most famous cycle of poems, Requiem, was written about the experience of women waiting for news of relatives who had been arrested in the 1930s. Composed between 1935 and 1940 at a time when the population of the prison camps almost doubled, Requiem was not published until 1962 in Munich and even then without the knowledge or consent of the author. It is an 11-page poem about the worst imaginings of people pining for their loved ones, not knowing whose fate is worse — the ones sent away or the ones left behind:

"Mountains bow down to this grief, Mighty rivers cease to flow.” “For someone a fresh breeze blows, For someone the sunset luxuriates -- We wouldn’t know, we are those who everywhere/Hear only the rasp of the hateful key...” “And it’s not clear to me/Who is a beast now, who is a man, And how long before the execution.” We are not talking Doris Day here. And yet somehow Akhmatova always finds a chink of light: “But hope keeps singing from afar...” “Never mind, I was ready. I will manage somehow.” “Today I have so much to do; I must kill memory once and for all,/I must turn my soul to stone, I must learn to live again...”

In the introduction to Requiem, she quotes a woman in the prison queue who asks her: "Can you describe this?" The word "describe" in Russian — "opisat" — contains the root of the word 'to write" — "pisat." She is not just asking her a rhetorical question about whether she can find the words to describe this situation. The woman is asking Akhmatova to write about it. In a very simple way, she is saying: "Someone needs to bear witness. You’re a writer. Do you think you’re up to it?" She tells the horror of an everyday moment very simply and without melodrama. She is the voice of a time when no-one wanted to speak. In Requiem she says it best: “Forget how that detested door slammed shut/And an old woman howled like a wounded animal/And may the melting snow stream like tears/From my motionless lids of bronze,/And a prison dove coo in the distance, And the ships of the Neva sail calmly on.”

She’s not an obvious candidate for someone to cheer you up. Few writers have catalogued misery in such forensic, lyrical detail.

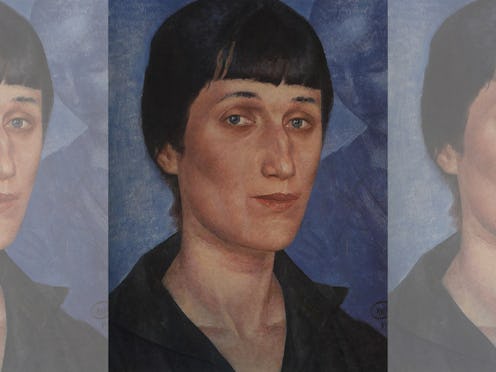

Sadly, though, beyond Russia, Akhmatova’s name is barely known now to anyone outside of academic circles or among those who take a special interest in Russian literature or in poetry. But Akhmatova’s status within her own lifetime was huge. Born in 1889, she was a sort of Russian Virginia Woolf. Later on, she became the unofficial dissident poet for the Stalinist age, writing her secret poetry about the horrors of waiting in line for news from the Gulag. I don’t even think there is an English language poet whose appeal comes close to the appeal that she has for Russians, a love which is compounded by the fact that she is easily the most famous female figure in Russian literature. Professionally persecuted, psychologically tortured, and ostracized by the state, she made it to the age of 76, outliving not only many of her peers but Stalin himself. She never stopped writing. She never stopped trying to make a difference. And, perhaps, most extraordinarily of all, she never stopped hoping. She may possibly be one of the most optimistic people ever to have lived.

She never stopped writing. She never stopped trying to make a difference.

In St Petersburg in the 1990s, it was assumed that you were interested in Akhmatova if you were (a) learning Russian and (b) a woman. You couldn’t possibly be serious about learning Russian if you hadn’t read any of Akhmatova’s poetry, especially if you were a woman. Akhmatova’s gender weighed heavily on her during her lifetime as she knew that everything she wrote was supposed to represent "the woman’s experience." And yet at the same time, her work was criticized for being “too much about the woman’s experience.” No wonder she had to be ballsy and determined just to keep going. Her writing is harsh and clear-eyed: “No, not under the vault of alien skies, And not under the shelter of alien wings -- I was with my people, then, There, where my people, unfortunately, were.” (Is there any better way of saying: “This really happened to us. I was there. And it was hell.”)

As if all this wasn’t already a huge burden, much of her work was produced in impossible circumstances. She couldn’t publish because she was not on the list of writers approved by the state. She couldn’t even physically write anything down because her home was routinely searched by the KGB, as were the homes of all her friends. It was illegal not only to publish anti-state material but to write it at all. To avoid her poetry being confiscated, Akhmatova’s poems were preserved in what was known as “pre-Gutenberg conditions.” They were part of oral history, not written down, just remembered, in the way poetry had been “written’ (ie. committed to memory) for years before print was invented. Nadezhda Mandelstam, the wife of the poet Osip Mandelstam, writes about how impressed she was with how discreet Akhmatova was about composing her poetry. Nadezhda had witnessed her own husband writing poetry to himself and judged that Akhmatova was much less “open”: “She did not even allow her lips to move, as M. did so openly, but rather, I think, pressed them tighter as she composed her poems, and her mouth became set in an even sadder way.”

In the early 1960s Akhmatova revealed that she had entrusted 11 people with her work. "Eleven people knew Requiem by heart, and not one of them betrayed me,” she said. Some poems were not written down anywhere until years later. Fortunately, Akhmatova’s friend Lydia Chukovskaya had an extraordinary gift for memorizing poetry. She and Akhmatova had a process. Chukovskaya recalls, “Suddenly in mid-conversation, she would fall silent and, signaling to me with her eyes at the ceiling and walls, she would get a scrap of paper and a pencil.” Akhmatova would then say something for the censors (who had bugged the apartment) to hear. Two popular choices were “Would you like some tea?” or “You’re very tanned.” Then she would note down a couple of lines on the scrap of paper and hand it to Chukovskaya to memorize. (I don’t even want to think about the pressure that this poor reader was under.) Once Chukovskaya had learned her lines, she would hand the piece of paper back and Akhmatova would say loudly, “How early autumn came this year.” She would then burn the scraps of paper over an ashtray. I can’t even begin to imagine the presence of mind that Akhmatova must have had to keep it together mentally under these conditions.

As if all this wasn’t already a huge burden, much of her work was produced in impossible circumstances.

The context in which people read Akhmatova during the Soviet era and just afterwards was, of course, deeply patriarchal. Even as recently as the mid 1990s in Russia people reverted to a deference towards women that verged on something out of Jane Austen’s time, as I discovered when I lived there. It was common for men to kiss you on the hand upon meeting you, to pull your chair out for you, light your cigarette, pour your wine. There’s a 1997 documentary made in St Petersburg about a group of people all turning 40 on the same day, and at one of the birthday parties, a man says deferentially to his lady friend, almost lisping with subservience: “Please, may I cut you a thinner gherkin?” If people were drinking, the first toast would be to the person hosting the party. The second would be “to the lovely ladies.” At parties there was a general assumption that “the ladies love sweet things” and people made a great show of bringing out cakes and chocolates at every social event “for the ladies.” Because ladies must have a sweet tooth! And ladies must love poetry written by another lady! This is all nonsense, of course. When I think of her playing the KGB at their own game, carefully recruiting the right circle of trusted people to learn her words and scribbling things on paper only to set light to them minutes later, all to avoid being killed for writing poetry... Well, it makes me want to scream. Or wield a Samurai sword. The highest expression of femininity? I don’t think so. This is the bravest of human acts. It has nothing to do with being a lady. It’s about being someone who “stood for three hundred hours/And where they never unbolted the doors for me.” That is the voice not of femininity but of humanity.

Adapted from The Anna Karenina Fix by Viv Groskop, published by Abrams 2018.