News

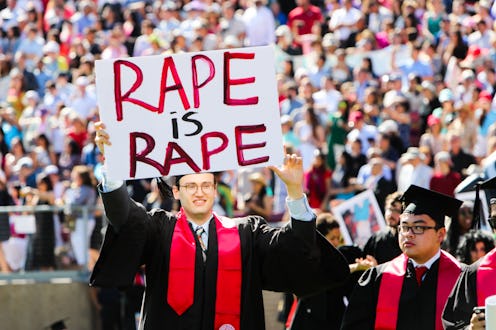

Here's How Different Universities Have Punished Students Who Violated Title IX

In her announcement about the Education Department rolling back the Obama-era Title IX sexual assault protections, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos suggested the current system is unfair to students facing accusations of sexual misconduct. Her decision — as you might imagine — has already proved controversial. But to comprehend the backlash to DeVos' decision, it's important to understand the system in place now and how schools punish students accused of sexual assault in current Title IX investigations. Although an Obama-era directive sought to outline policies for addressing Title IX complaints that pertain to sexual discrimination, there's less uniformity when it comes to punishment.

While Title IX clearly states that "no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance," it was initially not commonly interpreted to define acts of sexual harassment or assault as discrimination. However, over the years the issue of sexual assault on campus became more pressing until, in 2011, the Obama administration issued a new directive via the "Dear Colleague Letter."

In its "Dear Colleague" letter, the Education Department's Office for Civil Rights notified schools that acts of sexual harassment or sexual violence were now being quantified as an interference with "students' right to receive an education free from discrimination." This meant rape, sexual harassment, and other forms of gender-based violence were now considered to be a violation of federal anti-discrimination law, as outlined in Title IX. Schools were told they were required to "take immediate and effective steps to end sexual harassment and sexual violence" or risk losing their federal assistance.

While much of the "Dear Colleague" letter focuses on outlining procedural requirements for Title IX hearings and investigations into allegations of sexual assault and harassment, it does note that if such harassment is determined to have occurred, the institution "must take immediate action to eliminate the hostile environment, prevent its recurrence, and address its effects." This, the letter dictates, can include "taking disciplinary action against the harasser." However, the letter does not attempt to specify or limit what constitutes appropriate disciplinary action and schools have not all issued the same punishments.

For example, in 2012 when a male student was found responsible for sexual misconduct at Michigan State University, he was punished with a series of sanctions that included probation, education counseling on sexual harassment, and being barred from contacting his alleged victim in any way including entering the dormitory where she lived.

In 2014, a male student at the University of Kansas admitted to continuing to have sex with a female classmate after she'd said "no," "stop," and "I can't do this." He was slapped with probation, banned from university housing, ordered to get counseling, and write a four-page paper reflecting on the incident. That same year, a University of California at Santa Barbara student found responsible for sexual assault was suspended for three months but not forced to have notification of the sexual assault noted on his transcript. In Massachusetts, a male student found guilty of sexual assault at Brandeis University was punished with a warning and mandatory sensitivity training.

In 2015, a Stanford University student was found responsible of violating the university's sexual misconduct and assault code. He was suspended for five academic quarters (including summer), meaning he would not get his degree on time, but could essentially return to the university. According to Slate, such punishments were typical for Stanford, which expelled only one of eight students found to have committed sexual assault between 2005 to 20011.

However, not every university relies on such lax punishments. Multiple students found responsible for sexual assault have been expelled from their universities, including three football players from Purdue University earlier this year. But lenient punishments may, unfortunately, be more common. In a 2014 analysis of campus sexual assault cases, the Huffington Post learned that students found to be responsible for sexual assault were only expelled from their university in fewer than one third of the cases. In fewer than one half of the cases, the students found responsible were suspended.

As the Trump administration moves to change how schools handle such allegations, advocates for sexual assault survivors are concerned DeVos is placing too strong an emphasis on the idea Title IX is hurting so-called "falsely accused students," citing statistics that say 2 to 10 percent of reported rapes turn out to be false.

Ultimately, while the Dear Colleague letter forced schools to respond to allegations of sexual assault, it left much to be desired when it came to determining proper punishment and ensuring due process. Certainly sexual assault on campuses is, and will continue to be, one of the most controversial issues handled by the Department of Education.