News

How Our Legal System Fails Women Every Day

It can be fun-slash-harrowing to peruse through old and outdated "laws" that have yet to be taken off the books. For instance, did you know an archaic law stipulates that unmarried men in Illinois are to be called "master" by women? Or that Missouri makes it unlawful for more than four women to rent a place together? Harem fears, I suspect. These laws are not enforced, obviously. (Either that, or a whole lot of dudes in Chicago never reported me to local authorities.) But they do shed light on previous eras in which women were clearly treated as second-class citizens — or worse. And unfortunately, but perhaps inevitably, some of that residual sexism shows up in the laws of today.

Justice can be a difficult thing. We have laws, written by humans. Then we have the interpretation of those laws, also carried out by humans. Those two elements of any government's legal system alone are fraught with complication. What is right? What is wrong? Who gets to decide?

To be clear, this is not a uniquely American issue. It's one our entire species cannot escape, regardless of history, nationality, or the presence or absence of good intentions. And that's before you even arrive to the third step in this process: enforcement.

On all three counts — the writing of the law, the interpretation of the law, and the enforcement of the law — I would argue that most sexist laws in the country surround sexual harassment, abuse, and sexual assault. The particular unjustness of America's system is in how it minimizes the impact these crimes have on their victims (a majority of whom are women), especially in comparison to what has been deemed "fair" punishment for other types of illegal activity.

I'd like to pose this question to the American people: Is drug abuse worse than sexual assault? At the federal level, anyone selling 28 grams of cocaine or more will be given a mandatory minimum sentence of five years. There is no mandatory minimum sentence for rape from the federal government, and even when states do pass such laws, there are plenty of naysayers who seem far more concerned with the rapist's well-being than what justice for such a heinous crime might actually mean or entail. After all, if "punishment" for crime is just therapy and love, what message does that send to victims and their families? This isn't an easy question to answer, but in the case of crimes against women, it seems that plenty of people on the left and right are none too concerned with even grappling seriously with them.

And when it comes to the legal system, sentencing outcomes often indicate that our justice system regards violent crime against women as not particularly atrocious.

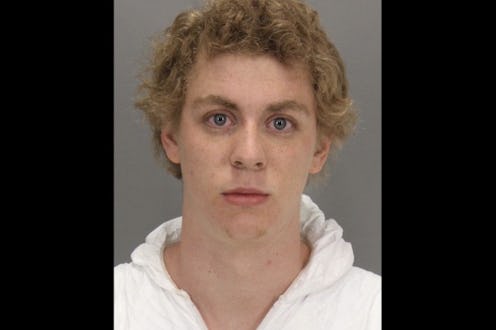

The most infamous recent example of this is the case of Brock Turner. The student from Stanford was caught by two witnesses sexually assaulting a woman who was unconscious. And there was a pretty clear indication that he knew the wrongness of what he was doing — the fact that he ran from the two graduate students who saw him. Even with witnesses, which most rape cases don't have, even with a guilty verdict, and even with the prosecution recommending six years of prison, the judge gave Turner just a six-month jail sentence.

Here, the enforcement of the law failed. Judge Aaron Persky decided to drastically reduce both what the law allowed and how it had been interpreted by just about everyone except himself and Turner's family, not to mention judicial precedent. The average sentence for a convicted rapist is between eight to 20 years.

In response to the public outcry at Turner's lenient sentence, Gov. Brown signed legislation that had passed in California's legislature to require mandatory minimum sentences for convicted rapists.

But as Danielle Paquette at The Washington Post chronicles, the Brock Turner story is by no means the only case in which a convicted rapist is shown extraordinary leniency. In Montana, a male teacher found guilty of raping a 14-year-old student was initially sentenced to just 30 days in jail. A case in Dallas in 2014 saw a judge give a grown man five years of probation for raping another girl just 14-years old. In the first case, the judge justified it because the survivor "seemed older than her chronological age." That girl killed herself in the middle of the trial. In the Dallas case, the judge partially defended his decision because the young teen "wasn't the victim she claimed to be."

Clearly, the law failed. These are heartbreaking examples of victim-blaming that illustrate how sexism — clearly a force against girls as well as adult women — can result in gross injustice.

But the devaluation of women in the legal system shows up in smaller ways, too. Take the so-called tampon tax, for instance. State sales tax policy usually makes exemptions for mandatory items, like groceries and prescriptions. Yet women have been paying an extra tax on sanitary products that every adult knows are not optional. As Christina Garcia, an assemblywoman from California, put it, "Basically, we are being taxed for being women." I find it hard to believe that if men had a period, they would have written tax codes designating maxi pads as "luxury" items.

The two examples here represent the extreme ends of a spectrum — the woefully unpredictable system for dealing with rape on one end, and the sales tax on feminine hygiene products on the other — an issue so seemingly minor that it went largely unnoticed for decades. In the big scheme of things, I'm exponentially more concerned with the former. Our criminal justice system needs reform on so many fronts, and this is one of the most crucial.

But it is also important to point out less obvious ways that women can be minimized or taken advantage of. Less than 100 years separates today from 1920, the year the 19th Amendment finally gave women the right to vote. And while it is a noble ideal that everyone be deemed equal under the law, there's a question here that needs a better answer: What if the law itself is unjust?