Books

YA Lit Is Leading The Push For More Queer Disabled Representation

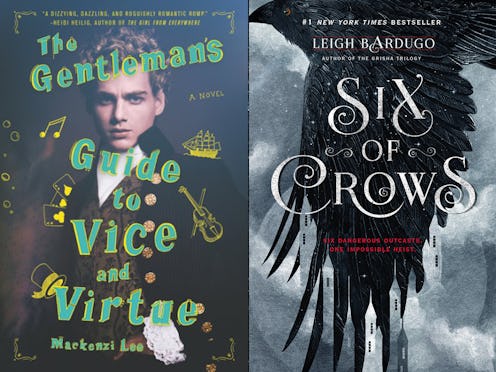

I love a good historical fantasy, so I picked up The Gentlemen’s Guide to Vice and Virtue on the day that it was published, because I have been dying to read something more than non-canonically romantic subtext between queer characters before the year 1900.

I was not disappointed.

What I didn’t expect was to get well-rounded, solid representation of a queer disabled character of color in Percy, who the protagonist, Monty, is trying to swallow his feelings for after years of being his best friend. I’m the queer girl who is dating her best friend after a year of unspoken romantic feelings, so I spent most of the book in fraught tears. My girlfriend was exhausted by me shouting, “Just be together, dammit!” across the living room at my copy.

As a queer disabled person, it’s not often that I see myself in media. I’m still waiting for a TV series that will finally have a physically disabled or autistic feminine character at the forefront; it would just be a bonus if she also dated women. But even though we have a long way to go, young adult literature is currently paving the way for the queer, disabled media revolution that we absolutely need.

The Gentleman's Guide To Vice And Virtue by Mackenzie Lee

Books like The Gentlemen’s Guide to Vice and Virtue by Mackenzi Lee, Otherbound by Corinne Duyvis, the Six of Crows duology by Leigh Bardugo, History Is All You Left Me by Adam Silvera, and Far From You by Tess Sharpe are bringing queer disabled characters and stories into the mainstream.

According to Lee & Low’s 2015 Diversity Baseline Survey, 92% of publishing industry staff members are nondisabled, 88% identify as straight or heterosexual, and 99% are cisgender. It doesn’t come as a surprise, then, that progress is slow. There are a few awards for LGBTQIA+ books, such as the Lambda Literary Awards and the Stonewall Book Award, but not any well-known counterpart for books with disability representation. While I was reporting this story, I asked everyone I interviewed and, more informally, my social circle who their favorite LGBTQIA+ disabled characters were in any media. Not surprisingly, a lot of people gave me a blank look. “I can’t actually think of any,” was a common response.

The characters who were mentioned were most often from young adult literature. “The greatest review I’ve gotten was from a reader who said she was bisexual and disabled and loved adventure stories but never thought she’d see a character like her in one until she read my book,” Mackenzi Lee, author of The Gentlemen’s Guide to Vice and Virtue, tells Bustle. It’s possible that young adult literature has more leeway to experiment than media like TV and movies, because it costs less to produce a book and there are fewer barriers to entry for authors and publishing staff than there are in film media, where it’s common to get your foot in the door through physical grunt work such as being a production assistant on set.

Not surprisingly, a lot of people gave me a blank look. “I can’t actually think of any,” was a common response.

But that doesn’t mean there are no barriers. Authors face the challenge of being told that their book is "too diverse," and that there’s already a disabled book or a queer book (or a book that’s both) on a publishing house’s list for that season. “When you're marginalized, it's hard to find yourself reflected in media. When you're marginalized in multiple ways, that difficulty is multiplied tenfold,” Corinne Duyvis, author of Otherbound, On the Edge of Gone, and co-founder of Disability In KidLit, tells Bustle. Duyvis also started the popular hashtag #OwnVoices to highlight books that are written by authors who share the same marginalized identity as their characters.

There are still a lot of common misconceptions about disabled people that affect how we’re represented in media, like the idea that we’re nonsexual and nonromantic by default, which lends itself to fewer stories about LGBTQIA+ disabled characters. “Readers may be surprised to see a wheelchair user revealed as a lesbian; they may not expect to see an autistic character casually talk about their sexual partners,” says Duyvis. It can be similarly unexpected when a disabled character is canonically asexual or aromantic, because that treats it as a valid part of their identity and confronts the audience with the idea that the character’s orientation may be completely separate from their disability.

It’s important that we have more stories with disabled LGBTQIA+ characters, particularly ones where the character’s entire identity isn’t about their sexuality, gender identity, or disability. “I think we need to have characters experiencing every possible thing, because no one story is ever going to resonate with everyone,” Hannah Moskowitz, author of Not Otherwise Specified, tells Bustle. “So the more stories you have, the better chance that a kid's going to find their story. The only way to satisfy everyone is to create quantity.”

That quantity is a big part of how YA books are leading the way — there are simply more stories at the intersections of LGBTQIA+ and disabled experiences. And authors are putting in the work to get representation right, whether they have #OwnVoices manuscripts or not. Annie Segarra, a queer Latinx YouTuber with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, suggests “consulting with several members of each community, paid interviews and group meetings, and hiring them to model, act, or write,” as a first step for authors and other creators.

"The more stories you have, the better chance that a kid's going to find their story."

Kayla Whaley, young adult and middle grade author and editor at Disability In KidLit, agrees with Segarra. “I think the research process for writing any marginalized character should actually start well before a writer or illustrator even conceives a story about that character,” she tells Bustle. “Learn the tropes common to whatever marginalizations you're writing. Understand why those tropes are problematic, why they're harmful.” Any tropes that exist are even more complicated when you’re writing a multiply marginalized character, which is why it’s important to read work by people who share those identities, and consider hiring several authenticity readers to consult your manuscript and help you get the representation right.

I haven’t seen stories like Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows duology — which has an entire cast including well-rounded, three-dimensional multiply marginalized characters and not just one for token diversity — in other forms of media.

Six Of Crows by Leigh Bardugo

“For so many of us, including me, intersectional identity is our real life, and it’s essential that we show our world on the page,” Anna-Marie McLemore, author of Wild Beauty, When the Moon Was Ours, and The Weight of Feathers, tells Bustle. “Going forward, I hope we see not just more LGBTQ+ characters with disabilities, but LGBTQ+ with disabilities who are of color, who come from a range of religious backgrounds, and who encompass many more intersectional identities.”

Those intersections are why characters from Adam Silvera’s They Both Die At the End and History Is All You Left Me resonate so well, and why I fell in love with Wylan and Jesper from Six of Crows. As a reader, you don’t feel like Silvera or Bardugo are checking off diversity boxes — they’re simply representing our world as it is. Particularly for teen readers, this is important. “People in that age group are often exploring not only their sexuality and/or gender, like many of their peers, but are doing so within the specific context of their disabled identity, which may itself be in flux!” says Kayla Whaley. “They deserve to see characters — multiple ones — navigating issues similar to the ones in their lives. And nondisabled and/or non-queer readers deserve to see them too.”

"For so many of us, including me, intersectional identity is our real life, and it’s essential that we show our world on the page."

This is particularly challenging when it comes to YA literature that’s also genre fiction, such as historical, science fiction, horror, or fantasy. Mackenzi Lee says that she did extensive research into the history of epilepsy treatments for The Gentlemen’s Guide to Vice and Virtue, as well as the problematic attitudes that exist today. “I didn’t want to put forth many of the stigmas around and incorrect treatments for epilepsy, particularly ones that could perpetuate harmful myths that persist today,” she says. “I wanted to find a way to make the conversations around it historically accurate but also be accessible and relatable to modern readers. But that’s always half the battle with historical fiction — figuring out where you draw the line between serving your readers and serving history.”

The way forward is for a major overhaul in media — a queer, disabled media revolution. And it’s starting with young adult literature. Young readers are slowly getting a canon of books that include intersectional stories and multiply marginalized characters. We’re seeing more #OwnVoices manuscripts, and authors writing outside their experience who are committed to doing the work and getting it right. The #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement and nonprofit that was created as a result are finding ways to encourage marginalized authors with grants, awards, and contests, and working to make publishing house staff diverse — because we really need LGBTQIA+ and disabled editors, reviewers, designers, illustrators, publicists, marketers, and production assistants behind-the-scenes, too.