News

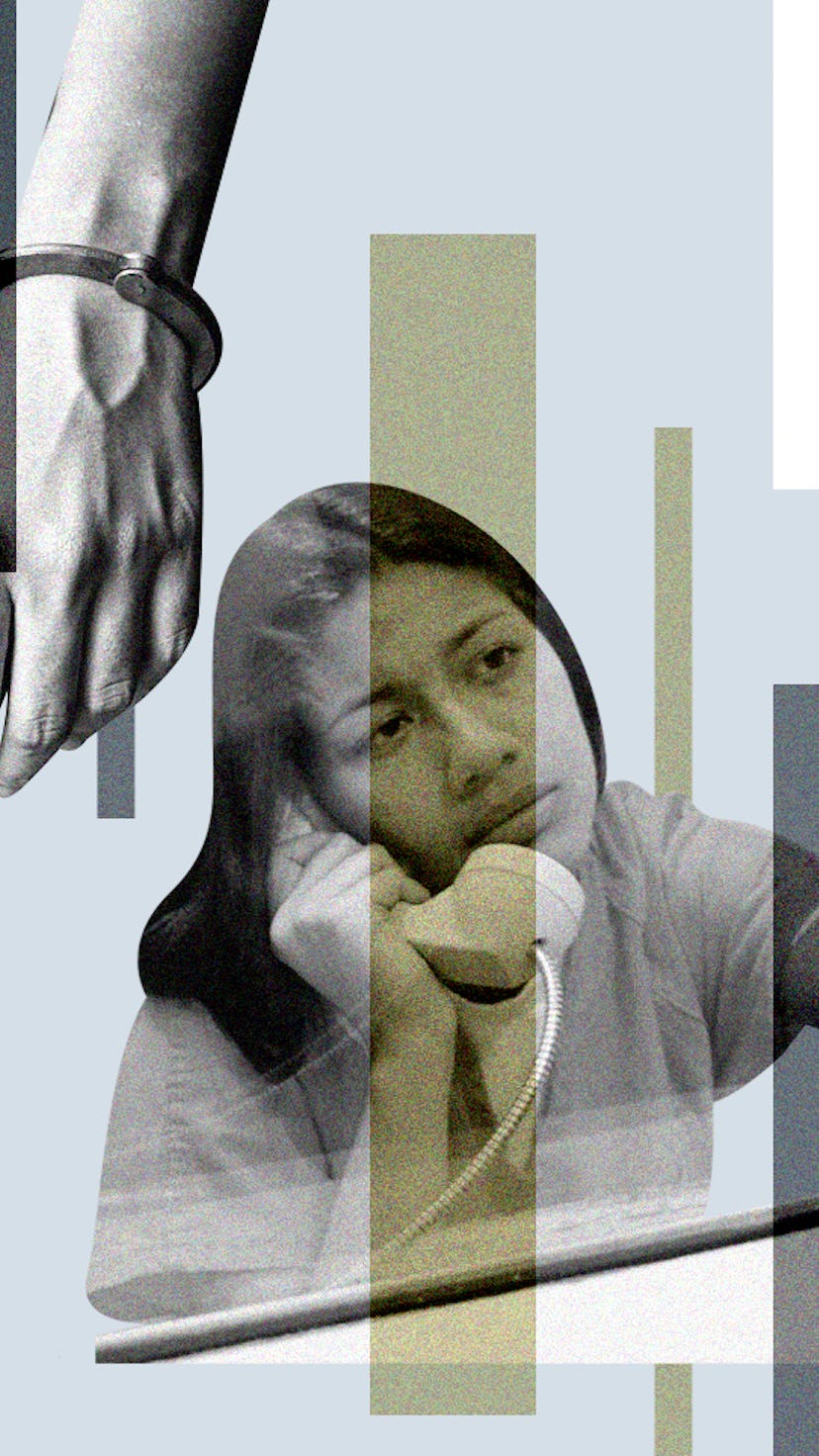

8 Women Experiencing COVID-19 Behind Bars

“As a woman, doing time in a California prison, there is this ever-present feeling of vulnerability,” an incarcerated woman named Michelle told me in a message she sent last week. “Ten-fold came that feeling of vulnerability when the novel coronavirus made its debut.” There are currently about 230,000 women behind bars in the United States, a quarter of whom have yet to be convicted of a crime. Unless the country reduces the number of individuals held in local jails — such as by releasing people who are currently incarcerated because they couldn’t pay their bail — the U.S. risks adding 100,000 more deaths to its coronavirus toll, according to a study released Wednesday by the American Civil Liberties Union.

As a result of the virus, most facilities are on lockdown, which means prisoners can be confined to their cells and visitors are prohibited. People who previously had access to in-person counseling, classes, or work are now left without any support or distraction, and likely also have less freedom to move around their facility. These new realities are no small matter given that the vast majority of incarcerated women have experienced sexual violence in their lifetime and for whom mental health services and daily structure can be a lifeline. It also means that the 80% of incarcerated women who are mothers are unable to see their children.

The 80% of incarcerated women who are mothers are unable to see their children.

Bustle asked women currently or recently held behind bars to share how the coronavirus has changed their lives. We received responses from jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers across the country. They expressed frustration at how little information they were given about the disease and its spread. Some worried about their kids or family on the outside. They fumed about how little elected officials were doing to protect vulnerable prisoners, and stressed that many proposed initiatives to safeguard elderly and sick prisoners — including Attorney General William Barr’s March 26 directive to increase the use of home confinement — were not actually being implemented as planned. With the exception of one person, every woman wrote that they had no access to protective equipment or the ability to practice social distancing. Without the ability to protect themselves, all they can do is wait.

These accounts have been edited for length and clarity.

"Wondering whether our last visit will be the last time we saw each other."

Shebri, 36, currently incarcerated at Fluvanna Correctional Center in Troy, Virginia

The climate and mood has changed here in Fluvanna. This began around March 12 when the initial memos came out from the Department of Corrections outlining their awareness of the pandemic. This was their attempt at reassuring us that they had it all under control. From there, more memos came. On March 23, we were placed on modified lock. Then came the counselors’ request on March 30 for everyone to update their emergency contact and death notification paperwork. Blank forms were handed to all during count time. This was incredibly unnerving.

All prison time is hard when you are a mom. I often tell people that not having my children, or open access to them is the hardest thing, beyond all else, about incarceration. Now that the COVID pandemic is affecting prison life, many offenders, including myself, are not allowed to work. This creates more mental downtime. Torture for an incarcerated mom.

Prior to the pandemic, I was able to have contact visits when my children’s caretaker's finances allowed, and video visits. Now, all of that has been stripped, and we do not know for how long. This adds additional strain — the wondering whether the last time we visited will be the last time we saw each other. I pray I make it back to my [kids] and that this concrete cage is not the end of my journey.

'I have kidney disease and breast cancer.'

Kimberli, 61, currently incarcerated at Carswell Federal Medical Center in Fort Worth, Texas

The hardest time is at night. During the day, we pace the unit and watch the news. At night, it is a different kind of worry — we worry if we are going to wake up, what will tomorrow bring, will the Bureau of Prisons do what they are supposed to be doing and get those of us that are the most vulnerable out of here before the virus hits. The pressure I feel in my chest every day waiting and waiting is horrible.

I worry about my family, my daughter, my granddaughter and grandson, my great grandson who was born in the middle of this crisis. I want to live long enough to meet him.

I am here on a non-violent, first-time, white-collar crime. Prior to this I never even had a parking ticket. I have done 27 months on a 60-month sentence, but I have stage 5 kidney disease and stage 3 breast cancer. I have a request for release into my judge, which he has not signed yet, and I am still waiting on Carswell to release me under Attorney General William Barr's guidance that vulnerable non-violent inmates that are sick should be sent to home confinement. So far, no one at Carswell has talked to me…

I am trying to get out of here so I don't die.

"Bleach, disinfectants, and even extra shower time are 'too costly'."

Michelle, 56, currently incarcerated at Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, California

The staff ratio is broken down to approximately 80% male and 20% female, and, just on a regular day, we were demeaned, neglected, and ignored at request for any kind of help or compassion. Now we sit here, each and every one of us, wondering when it’s our turn to contract COVID-19. When it’s our turn to be left unsupervised and unchecked in our rooms and cells — left to die, because the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation [CDCR] refuses to spend extra money for enough protective gear and cleaners so that inmates can be as safe as staff. We ask for bleach, disinfectants, and even extra shower time and are denied as they quote it's too costly to provide more than they do on a normal day.

Still, the virus is a human problem, and to speak of what it’s like for female prisoners is selfish because I am certain the response by staff is the same on the male side. Tikkun olam [repair of the world], genderless, applying to all! It's terrifying to see how less than human CDCR really views us at the end of the day.

"At least do something to try to keep them safe."

Nicole, 25, recently released from Cook County Jail in Chicago, Illinois

They say they want non-violent cases out of jail to slow the spread of the virus, but what about those people like me, who are falsely accused of doing something considered violent, so they have to sit in there? I don’t feel like nobody is fighting for the inmates in that jail, especially the females.

I’m worried about the health of the women still at Cook County, I’m worried about their safety. I know they probably feel like they’re being forgotten. I know my roommate is still there. It’s hurting me because I know she didn’t do whatever she’s been accused of, and she has to sit there. I feel like, if you don’t want to release the females with very serious cases, at least do something to try to keep them safe, to keep them healthy. [The jail administration] don’t want to do that. They’re not taking measures to keep them safe.

"If they're not giving PPE to the staff, we're definitely not going to get them."

Lexy, 41, currently incarcerated at the Transgender Housing Unit at the Rose M. Singer Center on Rikers Island in East Elmhurst, New York

What shocks me about all this is there’s no official protocol in place. We had 9/11, we had all these other things happen — Hurricane Sandy, Hurricane Katrina, and it just shocks me there’s no protocol in place for anything. We’re just kind of making this up as we go along.

It’s my understanding after reading in Friday’s New York Post that a court petition was filed defending the correctional officers of the entirety of Rikers Island because they — the corrections officers — feel like their immediate health concerns are not being addressed in wearing masks and wearing face shields and PPE gowns and things of that nature. If they’re not giving them to the administrative staff of the facility, then we’re definitely not going to get them. Everyone’s just walking around further being exposed, and that’s pretty much where it stands right now.

I think that transgender people are even more at risk because of the medical concerns that we have. There’s one person on our unit right now who has a severe leg infection. I myself have asthma. We’re at a greater risk of catching COVID-19 and it’s really hard to know and sit back and watch the fact that if we need medical attention, we can’t get it.

"I'm in darkness in my cell."

Carolyn, 44, currently incarcerated at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York, New York

Everyone is in complete paranoia. Everyone’s afraid, for their families, for themselves. Everyone is walking around with masks and gloves. It’s really scary.

We’re locked in 23 hours per day. I think about getting out of my cell! A lot of us are going a little batty. I’m visually impaired, and I’m housed alone – so I’m in darkness. That’s it, I’m in darkness in my cell. I meditate and pray a lot, because if I didn’t do that, I think I would definitely be in a padded room or something.

It has to be through the grace of God that I’ve still got my sanity.

"I'm scared one of the officers or one of the new detainees is going to bring the virus here."

Yanelkys, 36, currently incarcerated at the South Louisiana ICE Processing Center in Basile, Louisiana

There’s no soap in the bathroom. There’s no toilet paper. The guards don’t wear gloves or masks.

They are still transferring people in, for example I was in the yard yesterday, and they brought new detained people into the center. I feel really bad. I’m scared that either one of the detention officers or one of the new detainees is going to bring the coronavirus here. I’m terrified.

Truthfully, it’s been really difficult to be in detention as a lesbian. But it’s also the same treatment here that I received in Cuba. For example, even this morning I went to shower, and there were two girls there, and they told me to wait for them to finish before I went in. All the LGBTQ women in this detention center are fighting to get out, just to be strong and move on. We are a united group.

We are desperate, we are waiting to be freed for many months, and we have complied with all the requirements necessary for us to be released, but they’re not releasing us.

"There are no secrets here."

Michelle, 71, currently incarcerated at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution – Framingham in Framingham, Massachusetts

The general mood here is rather grim, an understandable response when others are charged with our care, and their personal and/or political concerns may not allow some of them to be as forthcoming as circumstances would require at a time like this. So I ask you, and everyone else outside these fences and walls, to speak truth to power whenever the opportunity arises; to scream it if necessary when lives are at stake.

The strangest thing about all this is that anyone who has lived or worked in a prison for any length of time knows that there are no secrets in these pain factories, only an unlimited supply of every type of unmitigated grief one could imagine; to be aware of it, and to allow it to fester, is one of our cultural failures.

Bustle would like to thank Immigration Equality, the Chicago Community Bond Fund, and NYC’s Inside/Outside Organizing Collective for connecting us to women interviewed in this story. Learn more about bail funds in your area here.

This article was originally published on