Books

This YA Historical Novel About Discrimination & Social Justice Is Painfully Relevant Today

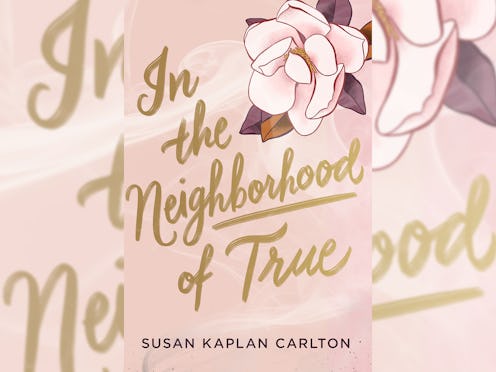

While it's not wrong to say that historical fiction can be a great genre to read when you want to take a break from current events, these books can also be a gateway to re-examining and understanding the many ways that history can repeat itself unless people make meaningful, positive change happen. Susan Kaplan Carlton's debut, In The Neighborhood of True, is a combination of both: romantic escapism brushes against harsh truths about discrimination and violence. Bustle's got the cover reveal and an exclusive excerpt from the book below.

In The Neighborhood of True, slated to hit shelves on April 9, 2019, follows Ruth Robb, who after her father's death in 1958, moves with her family from New York City to Atlanta — the land of debutantes, sweet tea... and the Ku Klux Klan. Ruth quickly figures out that in her new hometown, she can be Jewish or she can be popular, but she can’t be both. Eager to fit in, Ruth decides to hide her religion. Before she knows it, she is falling for the handsome Davis and sipping Cokes with him at the all-white, all-Christian Club. But at temple, Ruth meets Max, who is serious about the fight for social justice. When a violent hate crime occurs, Ruth will have to choose between her new life and standing up for what she believes.

Check out the gorgeous cover below! In The Neighborhood of True won't be hitting shelves until April 2019, but Bustle's got the entire first chapter below to tide you over until then:

In The Neighborhood of True by Susan Kaplan Carlton, $17.95, Amazon or Indiebound

Chapter One

The Whole Truth

1959

The navy dress was just where I'd left it, hanging hollow as a compliment behind the gown I'd worn to the Magnolia Ball the night everything went to hell in a handbasket.

"The navy dress was just where I'd left it, hanging hollow as a compliment behind the gown I'd worn to the Magnolia Ball the night everything went to hell in a handbasket."

I thought of Davis and his single dimple and how his hand had hovered at the small of my back, making me feel its phantom weight even when he wasn't touching me. I thought of a different day and a different dress, this one with sunburst pleats — how he'd unzipped it and fanned it out on the grass that night at the club, how the air was sweet as taffy, and how when we rejoined his family I'd wondered if every pleat was back in place.

"Ruth!" Mother's voice burst into the closet. "Not the morning to dillydally."

"Coming," I said, but I did the opposite of not-dallying. I put the navy dress on over my slip and sat, right there on the closet floor, not giving a fig about wrinkles. It was as if my nerves had pitched the world ten degrees to the left and I had to plunk down to find my balance.

It was cool at the back of the closet — in what I'd come to think of as my New York section, the land of navies and blacks and grays — where the floor was cement, smooth and solid beneath me.

When we'd first arrived here at the end of an airless summer, Mother, who'd changed from Mom to Mother when we crossed the Mason-Dixon Line, told her parents, whom we'd always called Fontaine and Mr. Hank, that Nattie and I needed wall-to-wall carpet to cushion our landing. Maybe we needed cushioning after the shock of our father's death, or maybe we needed cushioning after moving from our apartment in New York to our grandparents' guesthouse behind the dogwoods. Either way, the next afternoon, two men turned up with a roll of white carpet and stapled it over every square inch of the place, save for the closets.

"Maybe we needed cushioning after the shock of our father's death, or maybe we needed cushioning after moving from our apartment in New York to our grandparents' guesthouse behind the dogwoods."

Just like that, we were blanketed in an ironic, improbable snowstorm.

"Now, Ruthie," Mother said, on the other side of the door.

I stood up and pulled in, feeling the dread in my chest prickle from the inside out.

The dress reminded me of Leslie Caron in An American in Paris, except I was an American in Atlanta, and in the six months I'd been here, my taste and I had gone from simple to posh to simple again. If the girls in the pastel posse were in the courtroom today, I bet they'd be in shades of sherbet, rays of sunshine against the February sky.

Today, I didn't want to be sunny.

Today, I wanted to be Plain Ruth, teller of truth.

On the drive downtown, Mother said, "You be yourself up there, Ruthie. It doesn't have to get ugly." Her short bangs curled down her forehead like a question mark.

Here, nothing was supposed to get ugly.

"On the drive downtown, Mother said, "You be yourself up there, Ruthie. It doesn't have to get ugly." Her short bangs curled down her forehead like a question mark. Here, nothing was supposed to get ugly."

As we passed the putting greens on Northside, I watched the trees sway, thinking that winter was different — prettier — in a place where the trees cared enough about their leaves to hold on to them year-round. And also thinking that prettiness had to be planned, that the sprinklers had to work hard to keep the perfect green lawn from turning back to plain red clay.

I cranked down the window, needing to feel the air.

We were twelve minutes late. Mother was often late, a leftover New York affectation, but today my dallying about dresses had held us up. For a half second, I paused in front of the large door with Fulton County Superior Court etched in gold, then inhaled and turned the knob gently, hoping to avoid a clang.

Clang.

A hundred or more heads swiveled in my direction .

Mother dropped her smile, but then she touched her pearls and reassembled herself I followed her lead, hand to my throat, where my own string of pearls — along with my stomach and other major organs — had taken up residence.

The courtroom was impressive, with a soaring ceiling and sunlight flooding in from impossibly tall windows. It looked not unlike the temple at the center of the trouble.

"The courtroom was impressive, with a soaring ceiling and sunlight flooding in from impossibly tall windows. It looked not unlike the temple at the center of the trouble."

The pastel posse was here after all. I tried to catch Gracie's eye, but she was busy tugging her apricot twinset into place. Mother and I walked past Rabbi Selwick and his wife, both turned out in tweed, and I thought of him at our house with his daughter and her gift of peach preserves. Behind them were women in fur and men in pinstripes. The couples probably from the club looked like they were waiting for a tray of martinis to glide by.

Mother stepped into the third row, and I slid next to her. Davis was five feet away, at the defendant's table. The collar of his white oxford shirt, crisp and starched, poked out above his blazer. I couldn't tell a single thing Davis was thinking, from looking at the back of his very handsome head.

The attorney nodded to me and twisted his mouth . "You're late." To the judge he said, "We apologize for the delay, Your Honor. We call Ruth Robb to the stand."

My pumps click-clicked on the marble floor. A woman with coral lipstick motioned for me to sit in the witness chair, like on Perry Mason. Goose bumps inched up my arms. I wished I'd thought to bring a cardigan.

She turned to me and said, "Raise your right hand and repeat after me."

I raised my hand and noticed a sunburst carved into the paneling over the door I'd just walked through, a little moment of brightness.

"Other right," she said.

''I'm sorry." I raised my other hand. "I'm terrible with left and right. I always-"

"Miss-" the judge said, looking down at a note card. "Miss Robb. No need to talk now." He had gray hair and half-glasses, and he gave a half smile.

And I thought: But that's why I'm here. Because I couldn't keep my mouth shut.

The woman picked up a Bible, and I placed my free hand over its worn leather cover. I knew there were two Bibles — one for whites and one for Negroes. I knew because Rabbi Selwick was on a mission to have Negro witnesses use the same Bible as the rest of Atlanta. I thought about asking for the Negro Bible, even though every single person in the court room was white, but as the judge himself had said: "No need to talk now."

"Do you swear on this Bible the testimony you are about to give is the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?" the woman asked.

In the distance, I heard a sprinkler turn on. Tsk , tsk, tsk. I glanced at the worn leather cover of the King James edition, and it occurred to me I was swearing on the sacred text of another religion, that there wasn't a Tanakh for Jews to pledge their truthfulness upon.

I wanted Davis to look up. I wanted to see if his tie was straight. I wanted to see if he' d nicked himself shaving. I wanted to see the constellation of freckles across his eyelids. I wanted to see how he looked when he looked at me.

"I wanted Davis to look up. I wanted to see if his tie was straight. I wanted to see if he' d nicked himself shaving. I wanted to see the constellation of freckles across his eyelids. I wanted to see how he looked when he looked at me."

And then he did — his true-blue eyes locked right on mine. I felt the heat slide up my cheeks. Davis, who taught me about the Uncivil War, and blowing perfecto smoke rings, and real honest-to-God French- kissing. Davis, who said he wanted us to get married the second we turned twenty-one.

I swallowed. "I do."