Books

This New Book Is Tackling An Unconventional Topic — What Happens AFTER A Revolution

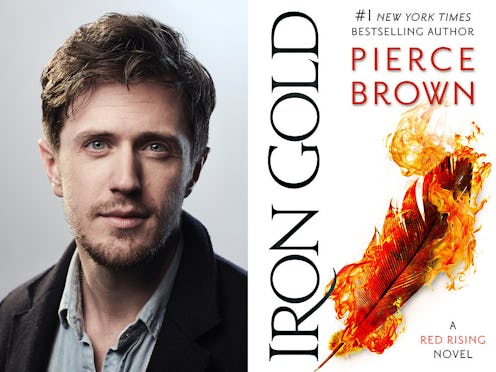

If you've paid attention to science fiction at all in the last several years, then you probably already know that the Red Rising trilogy by Pierce Brown has spawned a tribe of fiercely devoted readers, all of whom believed the space opera saga was over with the release of Morning Star in 2016. But, as it turns out, Pierce Brown has more stories to tell. Set in the same world, 10 years later, his new novel Iron Gold, out Jan. 16, contains all the star-scorching thrills and philosophical reflections of the first three books, but with a pioneering thrust: This book is not about revolution, but rebuilding. Death of oppressive governments is a well-trodden narrative arc, but Brown dives into a daring, oft-avoided question: When the tyrants are toppled, what rises from the ashes?

“Darrow, Mustang, and Sevro’s character arcs aren’t complete without this series,” Pierce Brown tells Bustle. “In a way this is the real test if they’re good people; if they are wise, if they are noble. The sacrifices and moral quandaries they have to face don’t come when you’re not wearing the crown.”

Be warned: Iron Gold is a heart-wrenching read – and you’ll devour it. As in his original trilogy — read them first, spoilers ahead! — action is interspersed with subtle reflections on relationships, government, loss, and loyalty. It’s “escapism you can learn from,” a phrase of Brown’s for other works I’m pilfering for his own.

"The sacrifices and moral quandaries they have to face don’t come when you’re not wearing the crown."

Readers will confront their conclusions about the titans shaking the solar system centuries into the future. Darrow, albeit world-weary, is still Darrow; readers just get an opportunity to scrutinize him and the world he’s trying to build from new angles.

Iron Gold by Pierce Brown, $17, Amazon

Literally: there are three new point of view characters in Iron Gold, and they all start breaking down the myth we’ve built around Darrow. Lyria, a Red recently liberated from the mines, Ephraim, a Gray disillusioned with the Sons of Ares and the Republic, and Lysander, the exiled grandson of former Sovereign Octavia au Lune, all offer insight into the pitfalls of Darrow’s Rising.

“Having only Darrow as the main protagonist in the books would be somewhat myopic," Brown says. "We’d be blinded to the social ills his revolution has created and the effects on people who are not superpowered. That’s a huge concentration for me in this book: exploring the world from the minds and lives of people who have been trod under the feet of giants. Darrow is a character who sees the cracks in the sidewalk but he doesn’t get to dive into the cracks because he’s a 7’1” killing machine. How can a 5’1” girl from the mines survive in Darrow’s world?”

"That’s a huge concentration for me in this book: exploring the world from the minds and lives of people who have been trod under the feet of giants."

Readers are plunged into the smells and starvation of Lyria’s assimilation camp, and reading Brown’s book, one has to wonder if he’s inspired by current events like the Syrian or Rohingya refugee crisis. While never venturing into the realm of being preachy, Brown’s books also don’t shy away from real-world problems — but the ideas aren’t just ripped from today’s headlines. When asked if he writes for current day relevance, Brown says, “The tragic answer is that could have been asked of me in any decade over the past 150 years. I think it’s incumbent upon a writer to be a student of history. You start reading these firsthand documents and start understanding we’re not at the end of history. It’s very tempting to play into the idea that our time is the worst it’s ever been, that our social ills have spawned from a golden age and we’re just trying to get back to that golden age, and I think that is just bunk. I try to write for patterns I see that are natural to the human condition of us living together in society. I also think if you are directly commenting on individual politicians, often you can become part of the demagoguery, and then your book is not posing questions to the reader; it’s posing answers masquerading as questions. I don’t feel it is my position or my place to tell people what to think. Instead, I’d like to hold up a weirdly colored glass they can look through their own world at.”

You’ll find other social issues addressed so subtly, you might not realize Brown’s books make a statement until you start thinking deeper about what you've just blazed through. For example, if it was a conscious decision to write dynamic, formidable female characters, it doesn’t feel like it. The inclusion of women among the most powerful world-breakers feels effortless. Mustang, the Obsidian queen Sefi, and the legionnaire Holiday – to name a very few – don’t feel like they were stuffed into the books to fill a diversity quota. They feel like people. “In terms of writing different voices, female or male, I don’t think it’s difficult,” Brown says, “as long as you approach every character with respect.”

Playing with gender has opened up new possibilities for him. Case in point: the ruthless Aja au Grimmus, one of the greatest Olympic Knights. “Aja in my mind was initially a man, but it wasn’t interesting,” says Brown. “Her name was Ajax, and then I changed it to Aja and everything started singing. I found her voice.”

And part of the point of Iron Gold, for Brown, is to make you wonder if Aja was “a good person doing the best she could with what she had or someone who enjoyed killing.” Moral ambiguity dominates all four books. Can good be found in evil people? Can the decisions of good people lead to evil consequences?

“You get to see how the unintended repercussions of good actions are often just as bad as the intended repercussions of bad actions,” says Brown.

The theme of myths people create also winds throughout the books. Eo, Darrow’s first love, becomes Persephone, spray-painted across buildings in lowColor districts, and Darrow himself becomes the Reaper of Mars. In Iron Gold, he has to face whether or not he believes in his own myth – and if he’s lying to himself about the answer. Darrow doesn’t smack of archetype, but it’s easy to see him as invincible, and Lyria, Ephraim, and Lysander begin to break that down.

“You get to see how the unintended repercussions of good actions are often just as bad as the intended repercussions of bad actions,” says Brown.

“Deconstructing myth is important because civilization needs myths, whether it’s a cult of personality, Republicans looking at Reagan as the myth of what a Republican should be, or even now Democrats looking at Obama. Yet the narrative of their rise to power and their time in power would show us a very different perspective,” Brown says.

Writing the new characters was a key worldbuilding step, but in the case of Lyria also seems to have been rather cathartic for Brown. “I think we’re always looking for a vessel to channel our own disillusionment with the current climate — you know, the current climate is always the worst one that’s ever existed — but for Lyria it actually is, so it was fun to have some noble indignation,” he says.

From political intrigue to high-speed action sequences to romance, there’s something in the books even for those who don’t typically read science fiction. But when fans start thinking about the futuristic, technologically-advanced world, one question quickly springs to mind: where are the robots? Brown divulged part of the world’s past that isn’t in the books to Bustle:

“This is something I haven’t put in the books: there was a Dark Revolt with the Obsidians but also a machine uprising on Earth. This was when the countries of Earth were still dominant, and it was defeated, but it wasn’t a small event and they saw it as a canary in a coal mine. So they banned robots, and that’s been almost indoctrinated within them,” Brown says. “They found it far more productive and efficient to have Reds working the mines, and the Reds were initially sent not just as miners but as colonists. By relying on human beings instead of robots, they thought human beings would be easier to control, at least less dangerous.”

The scope of the 18-billion-person solar system may seem dizzying, but at its core, Iron Gold is about identity and myth, according to Brown. He started writing the books when Darrow was around 16, just a few years younger than him. Shortly after the publication of Iron Gold, Brown will turn 30 — now a few years younger than Darrow, who is 33.

“Taking the quality of the analogy from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, I used to think I was a baked cookie; I was 19, but I was actually still just cookie dough,” Brown says. “Darrow in the other books had nothing to lose, but by book four, ten years later, he has all the things he’s afraid to lose. A wife, a child, friends, position, peace in certain ways, the liberation of his people. He knows how dark and sad the world is without them, and it creates a greater tear in him, and as he grows older I can’t imagine that tear ever abating.”