Within 24 hours of Donald Trump's election victory back in November, a retired lawyer in Hawaii named Teresa Shook had an idea. She took to Facebook to propose a protest around the time of Trump's inauguration. What started as an idea shared with a small group of friends rapidly gained traction when it wound up in the invitation-only Facebook group Pantsuit Nation. Thus, the Million Women March was conceived. Soon afterward, however, the Million Women March was renamed the Women's March on Washington for an important reason.

The march's original name came under fire for co-opting the names of the 1995 Million Man March and the 1997 Million Woman March, both of which were led for and by black people in the fight for black liberation and self-determination. Additionally, it was not only the name of the march that drew its fiercest critics, but also the fact that it was initially being organized primarily by white women.

Bob Bland, a fashion designer from Brooklyn who had proposed a separate woman's march before combining ideas with Shook, later conceded this point in an effort to be transparent about the march's origins. "It was, and is, clear that the Women's March on Washington cannot be a success unless it represents women of all backgrounds," Bland wrote on the Facebook event page for the march.

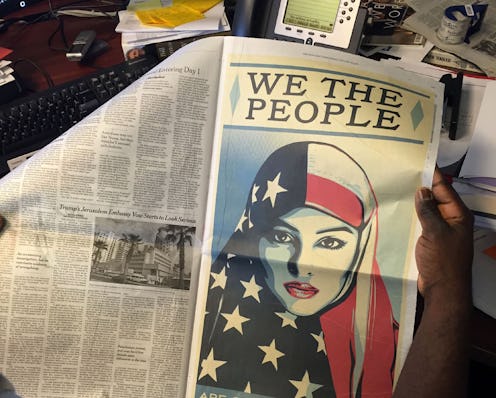

This was why, shortly after the Million Women March came into being, it was renamed the Women's March on Washington, and the original organizers brought three new people on board to be national co-chairs: Linda Sarsour, Tamika Mallory, and Carmen Perez, all three of whom are women of color and long-term organizers in their respective communities. The march's new name, too, was a reflection of black activism, but this time, it was intentional.

"These women are not tokens; they are dynamic and powerful leaders who have been organizing intersectional mobilizations for their entire careers," Bland wrote in that Facebook post.

Now voices including Asian and Pacific Islanders, Trans Women, Native Americans, disabled women, men, children, and many others, can be centered in the evolving expression of this grassroots movement. It is important to all of us that the white women who are engaged in this effort understand their privilege, and acknowledge the struggle that women of color face.

Even then, doubts remained about whether the Women's March on Washington would be inclusive and intersectional. Consequently, the team behind the march released an intersectional policy platform that called for reproductive freedom, solidarity with indigenous women, racial justice, an end to racist police brutality, LGBTQIA rights, equal pay, labor protections for sex workers, and more. This was clearly the right move, as the march now has sister events not only around the country but also around the world.

That the Million Women March became the Women's March on Washington was absolutely necessary. However, concerns about women of color being asked to once again perform the labor of making spaces inclusive are nonetheless valid. Therefore, with the Women's March less than a day away, it will be important for march organizers in Washington, D.C. and around the world to be accountable and cognizant about what purpose the march is really trying to serve.