News

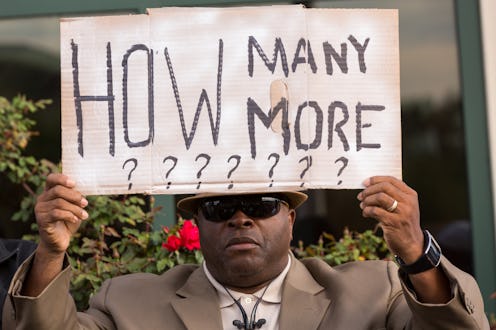

Jordan Edwards Is Proof There's Still Not Progress

On May 2, there appeared to be a first in the seeming epidemic of (mostly white, mostly male) police officers killing Black people. The officer who shot Walter Scott, an unarmed Black man whose death was caught on video in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, pleaded guilty to violating Scott's civil rights.

Michael Slager, the officer shown on video shooting Scott in the back as he fled from the scene, will have his murder charges dismissed as part of his plea deal. The news came the same day that the Department of Justice decided not to charge the officers involved in the death of Alton Sterling, a Black man killed in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, last year.

This news also came the same week as the police shooting of Jordan Edwards, a 15-year-old Black boy who was killed while in a car that was driving away from a party. Slager's guilty plea is not progress, and should not be taken as a sign that anything has substantially changed.

At first glance, these headlines could look like something akin to justice for Scott, who was 50 when he was shot and killed by Slager, and perhaps even as a sign of progress in America's fraught relationship between the police and the Black community. But a closer reading shows that Slager pleaded guilty to one count of violating Scott's civil rights by shooting him in the back, not to murder charges.

According to Charleston newspaper The Post and Courier, the plea deal Slager struck will result in the dismissal of his state murder charge along with the federal charges of "lying to investigators and using a firearm in a violent crime."

Slager's guilty plea admitted that he "used deadly force even though it was objectively unreasonable," and it's worth noting that the specifics of Scott's killing in many ways resemble that of Edwards, the teenager shot and killed by a police officer in a Dallas, Texas, suburb. The ongoing saga in the fallout from Edwards' killing has been complicated by inconsistencies in police retelling of the events. The officer who killed Edwards initially claimed that the car was backing up toward the officers in an "aggressive manner." A later statement from Chief Jonathan Haber retracted that account, stating that the car was driving forward, not backing up, and was moving away from the officers, not toward them.

Balch Springs policer officer Roy Oliver was fired in the wake of Edwards' death, the same day Slager pleaded guilty. But the claim of Black people menacing armed police officers has been placed on those who have died many times in recent history, from the initial reports of Edwards' death to those around Scott's, Michael Brown's, and so many others.

Scott's family and their lawyer have spoken about the sense of justice they feel they've received with Slager's plea. Chris Stewart, one of the lawyers for Scott's family, told The Post and Courier that the day was a big deal for both justice and civil rights:

Justice doesn't look like a big settlement check, it looks like today. Today is a monumental day ... for civil rights.

Scott's brother Anthony agreed, and said that "the healing begins today," now that Slager has told the truth about what he did to his brother. The family's statements are important, but it's also important to consider that within the broader context of Scott and Edwards' deaths and the context of race relations and police brutality, there's much more to be done in making justice preemptive rather than postmortem.

Slager's guilty plea may influence future court cases regarding police killings of Black people, but it will not bring Walter Scott or Jordan Edwards back to life, and it remains to be seen if it will deter the next officer involved in a similar situation from pulling the trigger. This is far from justice for Scott, Edwards, or the countless other Black people killed by police.