Sad news from the animal world today: Koko the gorilla has died at the age of 46, reports the non-profit organization the Gorilla Foundation. Born on July 4, 1971 at the San Francisco Zoo, Koko — whose full name was Hanabiko, meaning “fireworks child” in Japanese — was known for her communication skills; over her lifetime, the western lowlands gorilla learned and understood over 1,000 signs of a modified version of American Sign Language (ASL) referred to as Gorilla Sign Language (GSL) and 2,000 English words. She also demonstrated extraordinary depth of emotion, experiencing and communicating everything from love and humor to grief. She died in her sleep in Woodside, Calif.

Koko spent most of her life with animal psychologist Dr. Francine “Penny” Patterson, who first met the gorilla at the San Francisco Zoo in 1972 while conducting her doctoral research at Stanford University. Patterson formed the Gorilla Foundation in 1976 to acquire Koko from the zoo; after the acquisition, the foundation continued to support her research both with Koko and fellow apes Michael and later Ndume. Project Koko remains one of the most ambitious and high-profile great ape language research projects ever undertaken, bearing the distinction of being the longest continuous interspecies communications program of its variety across the entire globe, according to a piece published by the Telegraph in 2011.

Patterson began teaching Koko sign language when the gorilla was just one year old in what the Gorilla Foundation terms the “first-ever project to study the linguistic capabilities of the gorillas.” Koko didn’t tend to use grammar or syntax; additionally, as impressive as her vocabulary was, it’s generally agreed that it was at about the level of a 3-year-old human child. But she would sign strings of words which, when taken together, communicated her wants and needs — and the public loved her. Also, she flipped people off from time to time, which is honestly the most relatable thing ever.

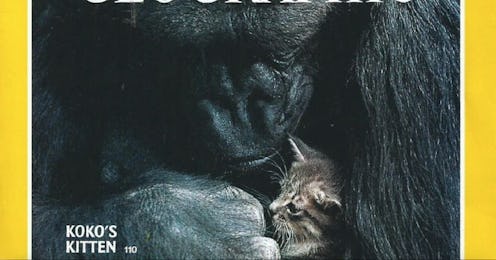

Although Koko often expressed a desire for a baby, she never mated; however, she did nurture a number of pets over the decades. She first asked for a cat for Christmas in 1983, according to the Associated Press, but was unimpressed with the toy cat she was given. So, for her birthday in 1984, she was allowed to choose a kitten from a litter of cats that had been abandoned: She chose a gray Manx and named him All Ball. (Manxes don’t have tails; it’s believed that her name for him was something of a joke — without a tail, he looked a little like a ball.) She cared for All Ball like a child and mourned him greatly when he escaped from her habitat and died in December of 1984.

Koko would care for other cats during her lifetime — after All Ball’s death, she adopted two more Manxes she named Lipstick and Smoky, and in 2015, she again received kittens for her birthday, Ms. Gray and Ms. Black — but All Ball, with whom Koko was pictured on the cover of National Geographic in 1985, seemed to remain close to her heart. Said Patterson to The Atlantic in 2015, “Even 15 years later, whenever she encountered a picture of a kitten that looked like All Ball, she would sign, ‘Sad. Cry.’ and point to the picture. She was still mourning after many years. “

Koko had also passed the mirror self-recognition test — a test developed in 1970 used “as an indicator of emerging self-knowledge” in nonhuman species which basically involves a creature looking into a mirror and being able to recognize the reflection as their own — when she was about 19. Said Patterson in an interview with The Atlantic in 2015, “[Koko] had been exposed to a mirror very early on. In the beginning, she looked behind the mirror for the other gorilla, but eventually came to use it as a tool and to groom herself and do all the activities that people do.” This was somewhat unusual for gorillas; it’s been theorized that gorillas tend to fail the mirror test because eye contact is perceived as an aggressive action, but that Koko and other similar gorillas may be able to pass it because they’re accustomed to interacting with humans.

Great ape language research, both in general and that conducted by the Gorilla Foundation specifically, has been criticized for both its methods and results. It’s been proposed, for example, that much of what human carers read from the gorillas under their charge is at least in part projection; additionally, when gorillas sign, they tend mostly to respond to questions posed to them by their carers, rather than offer independent commentary. The ethics of humanizing primates have also been questioned — as Barbara J. King pointed out at NPR in 2016:

“When Patterson started teaching ASL signs to Koko in 1971, little was known about interspecies communication. No one thought much about the ethical costs of turning a gorilla into a sort of hybrid animal caught between a gorilla world and a human one. Patterson's research project took on a snowballing life of its own, fueled by her own love for Koko and also by increasing media attention.

Now there's no other life that would suit Koko. She lives in a small circumscribed world of dialogues and games with caregivers, play with dolls, decorated cakes on her birthday — and her own credit card.”

But there’s no denying how wide-reaching Koko’s influence has been. Nearly 3,000 comments mourning her passing have been left on the post announcing the gorilla’s death on the Gorilla Foundation’s Facebook page. “This makes me so sad. Koko made me cry when she was alive —because I saw how much love she had to give and how kind she was to everyone around her. It was awe inspiring. To have such a gentle soul leave the earth... I am so sad,” reads one; “This is heartbreaking news! Thank you Koko for showing us humans what intelligence, love and compassion was all about. I have loved Koko since the beginning and will miss her forever. RIP beautiful girl and God speed. I know your kittens will be happily waiting for you,” reads another.

Twitter, too, is awash with messages about and tributes to Koko, ranging from sentiments like “I’m sitting here at work, about to go into a meeting, with tears welling up because I just read that Koko the gorilla died. Might not mean much, but I read ‘Koko’s Kitten’ over and over as a child, and that damn gorilla and stubby kitten meant so much to me” to “That’s it. The world is cancelled.”

In closing, I’m going to leave you with this video of Koko meeting Mr. Rogers:

That’s how you say “love.”