Books

25 Years Ago, This Book Changed The Game For Mental Health Memoirs

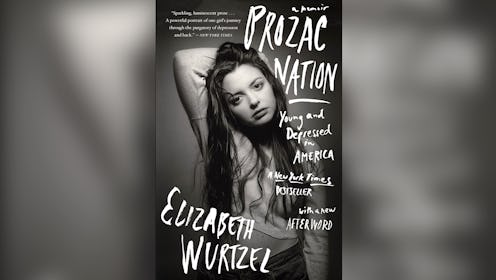

There are four Spotify playlists titled "Prozac Nation," one bearing the description "lo-fi tunes for numb teens who like to lie on their sides and stare at a wall and get sad and stuff." No description I’ve read in the 25 years since its publication has so accurately and succinctly captured the mood of Prozac Nation, Elizabeth Wurtzel’s memoir of depression and psychiatric treatment. In the book, Wurtzel reveals the very personal details of the mental health crises of her childhood, adolescence, and young adult years.

In Prozac Nation, published in 1994 when Wurtzel was 26 years old and adapted into a 2001 movie, she writes of her life as a depressed child of divorce, as a depressed teenager in New York City, and as a depressed student at Harvard and Cambridge. She talks of the messy mistakes, the drugs (both recreational and prescribed), and the strained relationships that marked those tumultuous years.

Such a youthful and revealing confession wasn’t common in the early ‘90s. For one, it was before the blog and personal essay boom. For another, though antidepressant prescriptions were on the rise (antidepressant use in the United States increased by 44.4% in the period between 1990 to 1993, and according to a study published in 2018, rates were still on the rise as of 2014), the stigma surrounding mental health was strong.

Though it may seem strange now, in the dawn of a "Prozac Nation," Wurtzel’s story was uncommon and her book was provocative.

Roughly two-and-a-half million prescriptions for Prozac were dispensed in 1988, not long after it became the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) to gain FDA approval. Wurtzel was one of those early adopters. Her admittance to a "Prozac Nation" was the culmination of a series of breakdowns in which she also took lithium and participated in extensive psychotherapy. By 1994, Prozac had been prescribed to more than six million people in the U.S, according to an article in The New York Times. In 2016, prescriptions for the drug numbered more than 23 million.

Matthew V. Rudorfer, M.D., of the National Institute of Mental Health, tells Bustle that from the 1950s through the 1980s, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) — early classes of antidepressants — were effective but complicated, and had to be closely monitored by a psychiatrist. SSRIs like Prozac, which treat depression by increasing serotonin levels in the brain, were developed and made available in the 1980s. Because they were believed to be safer and had broader use, they were prescribed more generously by primary care physicians.

In the dawn of this "Prozac Nation," Wurtzel’s story was uncommon and her book was provocative.

In September 1994, Prozac Nation was the subject of a scathing The New York Times review by Ken Tucker, which opened, "Instead of prescribing Prozac to depressive patients, doctors might now want to try something else first: give them a copy of 'Prozac Nation' and say, 'Read this; if you don't watch out, you could end up sounding like her.'" The review is dismissive of Wurtzel and depression as a serious health condition, and Tucker famously called her "Sylvia Plath with the ego of Madonna." He wrote: "The reader may well begin riffling the pages of the book in the vain hope that there will be a few complimentary Prozac capsules tucked inside for one's own relief." That same month, a slightly more forgiving The New York Times review by Michiko Kakutani cast Wurtzel as a prodigy and compared her to Joan Didion, Sylvia Plath, and Bob Dylan.

While Wurtzel’s memoir was seen, by some, as shockingly narcissistic and self-indulgent at the time, it probably strikes the modern reader as just a longer version of one of the thousands of mental health confessionals blaring from book shelves and online publications.

"A good memoir, however, isn’t simply the lived experience of trauma or grief, but rather it is finding in the very specific a universal truth.”

In fact, Amazon lists more than 300 "mental health memoirs" released in the first three months of 2019 (including reprints and paperback releases). In contrast, Worldcat (a catalog of content held by thousands of libraries around the world) lists only three titles described as mental health memoirs published in 1994. One is Prozac Nation and another is the paperback release of Susanna Kaysen’s 1993 memoir of mental illness, Girl, Interrupted. That both books are still discussed, sold, and circulated 25 years later is proof of their cultural relevance.

Though remarkably rare when they were published, these books gave birth to a thriving genre.

Literary agent Noah Ballard with Curtis Brown, Ltd. has worked on memoirs dealing with trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, and grief. "Everyone has a story of pain misunderstood, symptoms misidentified, and often loved ones lost," he tells Bustle. "A good memoir, however, isn’t simply the lived experience of trauma or grief, but rather it is finding in the very specific a universal truth.”

“What’s interesting are those books that attempt to capture mental illness in unique, new ways, as that catharsis of simply putting it on the page isn’t enough to capture a readership,” Ballard adds.

Today, mental health memoirs and nonfiction books dot bookstores and bestseller lists. Books like Esmé Weijun Wang’s recent memoir The Collected Schizophrenias, a New York Times bestseller, and Melissa Broder’s So Sad Today have received positive media attention and enjoyed market success.

Sarah Wilson, the author of 2018 New York Times bestseller First, We Make the Beast Beautiful (which, she says, is a conversation, not a memoir, about anxiety) was on her own mental health journey in the 1990s when she first read Prozac Nation.

“I was in the U.S. studying at UC Santa Cruz where I was diagnosed with manic depression, as it was called back then,” she tells Bustle. “I remember feeling awkward about how indulgent [Prozac Nation] was. It was the toe-gazing, self-conscious ‘90s and it was not a ‘done thing’ to be so self-absorbed and aware of your plight. At least not in such an earnest way. Things were more acerbic. But I felt it described what was actually going on. It almost provided the language for the discussion in coming decades.”

“I felt exposed just by looking at the cover.”

Chrissie Hodges, a mental health advocate and author of 2017 memoir titled Pure OCD was also unsure how to react to Prozac Nation when she purchased the book two years after a suicide attempt, psychiatric hospitalization, and a mental health diagnosis.

“When I saw the book on the shelf, I felt my entire body flush with heat because I had been on Prozac for over a year and a half and no one knew but my doctors and my close family,” Hodges tells Bustle. “I felt exposed just by looking at the cover.”

In a 2017 Guernica article, Charlotte Lieberman argues that mental health memoirs like Gorilla and the Bird by Zack McDermott reduce stigma with “a staunch resistance to shame, a traditional accompaniment to the disclosure of mental health issues.” Wurtzel was one of the first to do what dozens of writers are doing now — tell her personal mental health stories with a “staunch resistance to shame.”

Ballard agrees that prior to the 1990s, stigma kept mental health memoirs off bookshelves.

“There’s certainly a generational argument to be made about the rise of these sorts of memoirs. The same backwards logic behind keeping one’s emotions in and not seeking mental health treatment undoubtedly created that same void in book publishing,” he says.

Wurtzel closes Prozac Nation with a meditation on the death of Kurt Cobain, another icon of the dysthymia who characterized 1990s pop culture. She wrote that Nirvana "either inaugurated or coincided with some definite and striking cultural moments." Prozac Nation is arguably itself one of those striking cultural moments which ignited conversations about how we struggle with, survive, and sometimes fall to mental illness.

If you or someone you know is seeking help for mental health concerns, visit the National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI) website, or call 1-800-950-NAMI(6264). For confidential treatment referrals, visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website, or call the National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP(4357). In an emergency, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK(8255) or call 911.