Books

Mallory Smith Died Of Cystic Fibrosis Complications, But Her Mom Is Making Sure Her Story Is Told

"Cystic fibrosis is a disease that does a lot of taking — of dreams, of time, of travel, of friendships, of freedom, of potential, of plans, of lives," Mallory Smith wrote in the introduction to her journals. Mallory, who was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis (CF) at age three, died following complications from a double lung transplant in 2017, at the age of 25. This week, her memoir was published.

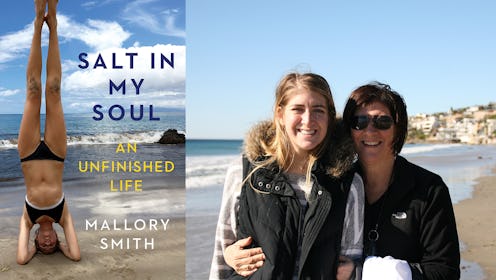

She left behind 2,500 pages of journal entries and instructions for her mother to publish her journals posthumously, hoping that her writing would offer insight to people living with, or loving someone with, chronic illness. Her mother obliged, spending the months following her daughter’s death reading, condensing, and editing Mallory's unfiltered words. The result is Salt in My Soul: An Unfinished Life, a moving portrait of an extraordinary young woman fighting to live a full life despite a devastating chronic illness.

"Mallory clearly understood early on that she was dealing with something much bigger than the average person’s day-to-day issues, and she seemed to just innately get the message, 'Don’t sweat the small stuff,'" Diane Shader Smith, her mother, tells Bustle.

The journals, which Mallory began writing at age 15 because of a fascination with legacy and memory, are raw — free from the self-consciousness of more conventional memoirs yet never without intention. Throughout their pages, she grappled with body image, depression, privilege, and identity. She chronicled her struggle to balance daily CF treatments — which can take hours — with her workload at Stanford University and later, her post-college life. She discussed the unexpected community she found in hospitals as well as the shortcomings of the medical system she depended on. She wrote about falling in love and yoga and the ocean.

"...she seemed to just innately get the message, 'Don’t sweat the small stuff.'"

An avid swimmer and surfer, Mallory thrived when she had regular access to salt water. “Ever since my parents threw me into the water at age three, the ocean has been my escape, my passion, and a powerful healing agent,” she wrote. Though her desire to travel the world was curtailed by her medical needs, frequent trips to Hawaii and the beaches of her hometown, Los Angeles, soothed her spirit.

Until the advanced stages of her battle, Mallory’s illness was largely invisible, despite the toll it took on her organs. She struggled to obtain disability accommodations "while looking perfectly healthy."

But from a young age, Diane helped Mallory help others understand the reality of her condition. “Many people that we’ve known that didn’t tell people ended up doing their treatments in private, which just creates more isolation. The disease is isolating enough as it is,” says Diane, who authored the children’s book Mallory’s 65 Roses in 1997 as a means of educating friends and classmates about cystic fibrosis.

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disease affecting about 70,000 people worldwide. A faulty protein disrupts the flow of salt in and out of the cells, causing a thickened mucus to form in the lungs and other organs. This sticky mucus makes the lungs particularly susceptible to repeated, harmful bacterial infections. While medical advances have increased average life expectancy for those born with CF, there is no cure.

She struggled to obtain disability accommodations "while looking perfectly healthy."

Mallory strove to “Live Happy," a mantra that guided her through pain and sickness and disappointment and doubt. Because her lungs were colonized by B. cepacia, an aggressive bacterial strain that became an antibiotic-resistant "superbug," she was an unlikely candidate for double-lung transplant, the one procedure that stood a chance at saving her life. (Most transplant patients with B. cepacia die within the first year from related infection, so the procedure is extremely risky.)

As her battle with CF progressed, Mallory — who previously authored The Gottlieb Native Garden: A California Love Story, which was published by the National Wildlife Federation in 2016 — expressed her desire to write a memoir. But then, in late 2016, a call came through: Mallory had been accepted by UPMC in Pittsburgh for transplant. “We got busy with the move, and then after transplant, [when the topic of memoir resurfaced,] she turned to me and said, 'The only problem is, Mom, I don’t even know what’s interesting about my story.'"

This modesty pervades Mallory’s journals. Writing clearly helped her understand something about her life, but her words extend beyond mere self-reflection.

"She wanted to share the parts that she knew would help other people," Diane says, adding, "It’s not what I thought it was. What I thought it was was a gift to the CF and transplant community. What I’ve come to understand is, they don’t need an explanation and they don’t need a road map... What [Salt in My Soul] is good for is anybody else, outside of that, whether they know somebody or not who’s going through chronic illness, cystic fibrosis, transplant..."

...she turned to me and said, 'The only problem is, Mom, I don’t even know what’s interesting about my story.'"

Talking with Diane, it’s easy to see where Mallory got her drive and determination, and also her poise and integrity. "The fact that she didn’t leave negative writing about me in the twenty-five hundred pages was indicative of her character," Diane says. In fact, Mallory clearly recognized her mother’s devotion. In one passage, she reflected on Diane’s strengths and said, "She is a role model in many ways. ...She taught me to prioritize love over all else."

But despite their closeness, even Diane was surprised by some of what she found in Mallory’s journals: "The depth of her suffering, even though I lived with it and I saw it, it was even deeper than I realized, which only made me have so much more respect for her perseverance and her ability to smile, the importance to her of being kind to everybody."

As Lori Gottlieb recently noted in a review of Julie Yip-Williams’ The Unwinding of the Miracle, memoirs of sickness and death "remind us to put in our own effort." Mallory’s journals join this canon. Whether invoking the poignancy of missing her dog while hospitalized or capturing the pleasure of a first kiss, Mallory’s words are all the more profound for how unscripted they are. The lack of stylization allows a keen emotional intelligence to shine through; Mallory possessed resilience and wisdom in spades.

"I’ve found that such is the task of a writer," Mallory journaled, "to help others understand and empathize with a life experience they’ve never lived." There is no sugar-coating in Salt in My Soul — dive in expecting a grit and beauty that mirrors the ocean Mallory so loved.