Books

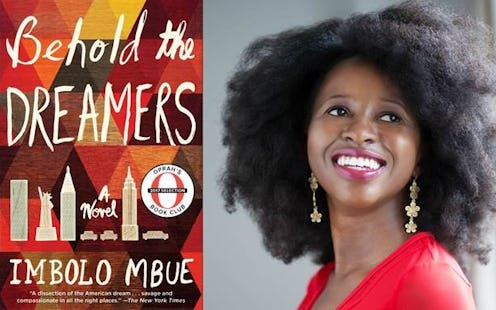

Author Imbolo Mbue On Oprah's Book Club, Donald Trump, And Empathy

The Washington Post called it “the one novel Donald Trump should read now.” Winner of the 2017 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, a 2016 New York Times Notable Book, an ALA Notable Book, and now named as the latest Oprah Book Club selection Imbolo Mbue’s debut novel, Behold the Dreamers, traces the lives of two very different families in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. But that’s just scratching the surface.

Published last year and re-released as a Random House Trade Paperback in June, Behold the Dreamers takes a poignant and multilayered look at immigration, wealth inequality, race, Wall Street corruption, marriage and family, motherhood, loss, and what it means when — during the long climb towards achieving your dreams — you cease to be the same person who dreamed those dreams in the first place. Insightful, suspenseful, and big-hearted it’s easy to see why Mbue’s debut is the novel readers can’t stop buzzing about, over a year after it first landed on bookstore shelves.

But the success isn’t something Mbue expected — or even really thought about, she tells Bustle in an interview, just days after her selection as the next Oprah Book Club pick was announced.

“At the time I began writing it, I’d never published anything so I didn’t have an audience to think about,” Mbue tells Bustle. “And when I started looking for an agent to represent me, the story was rejected right, left, and center. So, there was little indication that it would resonate with others at the level at which it has. It’s an immense privilege for me; I’ve been left with overwhelming gratitude for everyone who has shown me kindness in the things they’ve said and the ways in which they’ve supported this book.”

Behold the Dreamers by Imbolo Mbue, $13, Amazon

After the 2008 financial crisis during which Behold the Dreamers takes place, Mbue, a Cameroonian immigrant living in New York City, not unlike two of her novel’s main characters, Neni and Jende Jonga, lost her job in marketing and struggled to find a new one. Conflicted about which direction to turn next, the Rutgers and Columbia University graduate turned to writing, which is how Behold the Dreamers was born.

“It wasn’t so much losing my job that disconcerted me,” Mbue says. “It was the fact the country appeared so upside down. I’d studied hard, been a diligent employee, leaned in, and there I was with a great education and enthusiasm and I couldn’t find a job. During that period, it seemed as if every other day a company was shutting down or downsizing somewhere in the country. Looking back now, I realize how much my writing was a sort of refuge for me. When I got the inspiration to write what later became Behold the Dreamers, I found an even bigger refuge because in the lives of the novel’s characters, I was able to dwell less on how the financial crisis was affecting me and more on how it was affecting other people around me.”

In Behold the Dreamers, Jende has long overstayed his three-month United States visa while his wife, Neni, is in the country on a student visa, leaving their small family less than secure. Renting a small apartment in Harlem, Jende takes a job as a chauffeur for senior Wall Street executive Clark Edwards, whose own wife, Cindy, employs Neni at the family’s lush summer home in the Hamptons.

“My immigration story has some parallels to theirs. Like them, I moved from Limbe, Cameroon, to the United States, though I came here at a younger age to attend college, unlike Jende and Neni who moved here as adults,” says Mbue. “I lived in Harlem for several years, so like them, I was also an African immigrant living in Harlem. That, however, is where much of our similarities end — most of their story, and the struggles they endured, was inspired by stories told to me by other immigrants.”

For the Jongas, the possibility of being awarded citizenship seems tangible. Sure, they’ve got a questionable immigration lawyer and their yearly salaries might not go nearly as far as they imagine, but both are comfortable in their jobs and Neni is studying for a pharmaceutical degree. Until the economy collapses, that is, and everyone from the topmost executives to the housekeepers they employ is suddenly at risk of losing everything. As is true for many immigrants like the Jongas, their American Dream becomes an American Dream deferred — over and over again, until Jende begins to consider if life wouldn’t be better for his family back in Cameroon.

“It’s a complex and deeply personal issue,” says Mbue. “One I struggled with and one which the African immigrant characters in the novel struggle with — was it worth it to leave our homelands in pursuit of a better life which might remain elusive? Despite the challenges of an American immigrant experience, millions of people around the world still dream of coming to America to achieve the American Dream.”

I ask Mbue if, given the economic and political climate of the United States, perpetuating this narrative of the American Dream does a disservice to immigrants. “For many it is a worthwhile dream, a dream millions of immigrants and native-born citizens have achieved,” she says. “That, however, is not to say that the American Dream is accessible to all, because there are mountains of socio-economic challenges that stand in the way of it. But before coming to America, I didn’t understand this and if someone had tried to convince me I doubt I would have listened. It’s potent, this notion of the American Dream. We don’t hear people talking about the Australian Dream or the French Dream or any thing else along those lines because no other country has positioned itself as the land of opportunity the way America has. The America I saw on TV as a young girl in Cameroon was a sort of Promised Land and I had no reason to believe I would encounter otherwise.”

Behold the Dreamers takes a multi-faceted view of poverty and what it means to go without. While the Jongas work impossibly hard to make ends meet, their relationship is strong throughout much of the novel. They also have a close-knit community of friends they call upon without guilt or hesitation, and stay in touch with their family back home in Cameroon. The same cannot be said for the Edwards family, who are financially comfortable to excess but are distant from one another and emotionally isolated in ways that lead to destruction.

“I must say that one of the things that struck about America when I first got here was how different the sense of community was from where I’d been raised,” Mbue says. “Before my arrival here, I never knew there was such a thing as homelessness. In my hometown, if life got tough, you could always find a relative or neighbor who would take you and your family in. If five people had to share one bedroom, so be it. If we had to sleep three on a bed, c’est la vie. That is not to say the culture in Cameroon is better than the one in America — they’re very different, but I didn’t find the same richness of community that existed in my hometown of Limbe, Cameroon.”

In Behold the Dreamers, Jende and Neni get much of their information about America from television shows like The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, and films like Mrs. Doubtfire and American Beauty. I ask Mbue what she thinks is one of the biggest misconceptions immigrants have about the United States. She says, “I think we can acknowledge that while immigration has greatly contributed in making America the superpower it is today, there are many native-born citizens who have been left behind and haven’t necessarily benefited from the influx of immigrants into their communities. There are certainly broad socio-political issues at play here, but that doesn’t mean that as immigrants we cannot empathize with the citizens.”

I also wonder, in an increasingly hostile environment (or, to take the long view, an environment of historically fluctuating hostility towards immigrants) about the misconceptions American’s have about immigrants. “I think there’s so much focus on what immigrants came to America to gain and less emphasis on what we lost in our pursuit of this better life. The immigrant experience can be brutal — so many changes to get accustomed to, so many disadvantages by virtue of the fact that many consider us to be an “other.” And yet, we carry on, because there’s a reason why we left our countries in the first place. If our countries could offer us the things we seek, would we have left it in the first place to become strangers in a strange land?”

Despite the country’s flaws — past and current — Mbue’s words, both in Behold the Dreamers and throughout our interview, offer some much-needed (at least, to me) perspective on the current U.S. state of affairs. “I grew up in a country where we’ve had the same president since 1982 so I know I am definitely enjoying political privilege living in a country where presidents can be fired after four years!” Mbue says. “There’s a scene in the novel where Neni reflects that America might be flawed but it is still a beautiful country — I completely agree with that. In retrospect, I think writing this novel was a journey of exploring and celebrating the many different sides of my adopted country. I think being an immigrant gives me an advantage in appreciating America for what it is, because despite the numerous hardships I’ve endured in my time here, I still find myself in awe of what this country and the possibilities it offers.”

I ask Mbue if she agrees with the Washington Post assessment that Behold the Dreamers be required reading for the current U.S. president. “Do I agree with the assessment? Ha, ha,” she says. “It’s a bold statement and I am a fan of boldness. Writing this novel was a journey of empathy for me, and living in a time when the narrative of “us versus them” is very dominant, I think we could all do well to work on elevating our empathy. I believe, to borrow from Dostoevsky, that empathy will save the world."