Entertainment

‘The Boomerang’ Soundtrack Introduced Me To Love Before I Knew What It Was

Google tells me the soundtrack to the masterful, classic ‘90s film Boomerang was constructed in a mere two months. Meanwhile, despite me being only about a decade older than the soundtrack myself, and despite me having to sneak watch the film on VHS after my parents went to sleep as a kid, both works have stuck to my bones, giving me comfort and nostalgia I likely don’t deserve.

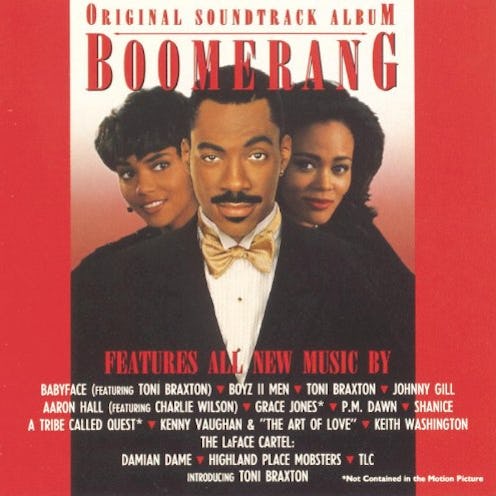

Spun together by the unstoppable early '90s crew of Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds, Daryl Simmons, and Antonio “L.A.” Reid, the Boomerang soundtrack has become a time capsule of sounds that seem ancient now: New Jack Swing, the husky contralto of Toni Braxton, the sentimentality of black boy-band R&B from the likes of Boyz II Men, and the otherworldly beauty of P.M. Dawn’s indelible sound. It also peaked at number four on the Billboard 200. The film and the soundtrack represented — along with soundtracks for other '90s films like the Tommy Davidson driven Strictly Business and the black-kid rite of passage soundtrack Waiting to Exhale— the introduction of a bourgeoise black urban middle class to a milieu of audiences. The film was an early whiff of things to come, perhaps not just for black romantic comedies, but for our lives.

Boomerang dropped in 1992 and was helmed by Reginald Hudlin, a Harvard educated satirist and director whose work included House Party and who would go on to become president of BET. “In some ways it was a dream, it was ideal,” Hudlin says of working with the iconic comedian. “I was frustrated that he had never had a cast that supported him comedically in the way that he deserved." Boomerang gave Murphy just that. He was buttressed by some of the premiere comedic talent of the time. To his right was Martin Lawrence. To his left, David Alan Grier. Those heavy hitters were backed by Chris Rock and Tisha Campbell. And of course, Boomerang became a breakout moment for budding star, Halle Berry. The film was a box-office hit for Murphy. On a budget of $42 million, it cashed in at $132 million worldwide with over $70 million in domestic receipts. The soundtrack did even better. It entered the Billboard 200 chart at number eight, before reaching its pole position at number four.

My own history is a byproduct of the socioeconomic tailwinds in which Boomerang was created. It was a decade after we found ourselves awash in a burgeoning artistic moment that aimed to disrupt blanket notions of race and class. All the while drug wars raged, the spectre of HIV decimated the black community, and corporate militarism ran amok. It was a magnanimous time, though fraught, and neo-black aesthetic essentialism was about to enter the mainstream.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s the United States was experiencing an intense nursing shortage. Soon the nation reached down into its colonial holdings and offered a sweetheart deal to those who heeded and had luck: an H1-B visa and safe passage for your immediate family in exchange for labor. My mother took that deal, as many Caribbean mothers did, and I ended up on a plane to the United States from my native Jamaica.

Four years later, I was a child in love with love ... How it could ground you in meaning in a life between two lives. Between my native Jamaica and my new home in New York. Between Caribbean patois and English. Between the harmonies of Boyz II Men and the rollicking swing of Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis as well as Teddy Riley.

The year was 1988, the hottest rapper alive was Slick Rick, and it was a snowy February in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn, New York when I arrived as a smiley 5-year-old with no concept of how R&B would impact my young life. For me, rap was still a ways off. My parents predominantly played R&B in our two-bedroom apartment on Parkside Avenue, and it was there I fell in love with the genre.

Four years later, I was a child in love with love. The idea of it. Its narrative. How feeling could leap into you. How it could ground you in meaning in a life between two lives. Between my native Jamaica and my new home in New York. Between Caribbean patois and English. Between the harmonies of Boyz II Men and the rollicking swing of Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis as well as Teddy Riley. There was much in that between. There was the strained huskiness of K-Ci’s decries on desire, Luther Vandross’ roiling longing, Anita Baker’s elegant moans. All of these outrageously talented artists held together by the more traditional R&B of “L.A.” Reid at one pole and the creators of New Jack Swing at the other. Or so things seemed to me, my tiny slice of America’s love language pulling me further into its embrace. And that’s when I encountered Boomerang, and shortly thereafter its soundtrack. Especially P.M Dawn’s “I’d Die Without You.”

P.M Dawn members Attrell Stephen Cordes, or “Prince Be,” and his brother Jarrett Cordes or “DJ Minutemix” made a kind of music that you could consider a precursor to today’s rhythmic polyglots like Dev Hynes, Childish Gambino and Frank Ocean. The band existed in a liminal space, three-fifths Massive Attack and one-fifths Isley brothers with one part Christian mysticism. Legendary critic Robert Christgau writing for the Village Voice called the group a “force for good in a world that generates too many misfits and not enough b-e-a-u-t-y.”

In the film’s quietest moments, it was “I’d Die Without You” that elevated itself to a character. The song was a paean to love, but more importantly it was one to authenticity. To my 10-year-old mind, P.M Dawn was a revelation. Something so alien it made me feel I belonged to it. To a separate world out there where people got down to stuff like that.

The song anchors crucial sections of the film, especially the end, where Murphy’s character Marcus whispers, “I can’t breathe without you” to Halle Berry's Angela. In truth, the characters were fighting for a sense of how to be young, gifted, and black in the world. Gen-X urban professionals of the time seemed to struggle with that idea. Now of two worlds, they had to choose blackness.

As a child trying to figure out ways to match the adult world with my inner universe, the film felt like a fever dream of off-kilter artistic references that I couldn’t understand.

That’s a sliver of what this soundtrack meant to me. I discovered Toni Braxton here when she shook my whole soul with “Love Shoulda Brought You Home,” as if I knew at the time what that really meant. Johnny Gill’s “There You Go” was the sweetest sounding foreplay construct I’d yet to hear. Grace Jones’ “7 Day Weekend” introduced me to the Jamaican-born supermodel and dance music superstar, and Boyz II Men’s “End of The Road” saw tears well up in my 10-year old eyes. More than anything, the soundtrack was overwhelmingly optimistic. It allowed me to dream past my wood-paneled childhood bedroom and into the future of my own family. To the woman I’d sing these songs to. And to the children we might have, who I’d introduce these artists to in much the same way my parents did, music filling our home with memories. Despite the times, a college-educated black urban class was living full lives, and I’d live mine too someday. One day.

As a child trying to figure out ways to match the adult world with my inner universe, Boomerang felt like a fever dream of off-kilter artistic references that I couldn’t understand. Grace Jones’ artistic savant of a character Strange was both a wild caricature and a vision. Young Halle Berry fogged up my square metallic frames. Shoot, I wasn’t even allowed to watch the film as a kid. It was blacklisted along with Married With Children and all the Nightmare on Elm Street flicks. In Boomerang, an essential part of the idea of blackness was at stake. Could we climb the corporate ladder and keep our souls? If you just go by the soundtrack, the answer was a resounding yes. It wasn’t a love we couldn’t live without, it was ourselves who was the “you” we’d die without.