Books

This Mother's Day, I'll Remember I Discovered Joy — Not Grief — After My Mom Died

Last week, I came across a Facebook post from a woman who wanted to know how other members of the “Dead Moms Club” would cope with the “upcoming holiday that shall not be named.” Over 80 women replied, and though their stories were different, their pain was the same. Each found Mother’s Day unbearably sad and difficult. Some plan to impose weekend-long media blackouts so sentimental commercials and happy Instagrams couldn’t find them, while others will distract themselves by volunteering. Many will take the opposite approach and spend the day acknowledging and embracing their grief. I’m a member of this club, too, but instead of joining the conversation, I studied it with envy and confusion.

My mother died from alcoholism in 2010. I was exhausted by her addiction, her lies and my dumb hope that things could change. I was also relieved. I no longer had to wonder if today was the day, if a call from my sister was the call. When I consider her dramatic decline, her life and its succession of tragedies, I feel very sad for her, but I am not sad that she’s dead. I don’t miss her, and I never have.

This response feels appropriate, but when I observe someone else’s grief, I worry that I’m defective, that my lack of sorrow indicates the absence of something vital and human. I wonder if I should feel the same way and what it would be like if I did. How incredible it must be to be that close to a parent, to adore them so much that their death leaves you in anguish, so comatose and unmoored that you find the world hollow. I’m not jealous of this pain because I know how powerful and destructive it can be, but I envy whatever produced it.

"When I consider her dramatic decline, her life and its succession of tragedies, I feel very sad for her, but I am not sad that she’s dead."

My mother was not a monster. She was funny and kind, and when I was young, very loving. She put herself through college and graduate school, traveled the world, and had an impressive career in environmental policy. I feel lucky that she was so ambitious and accomplished, that my primary role model was a woman who refused to let motherhood define or reduce her. If I were better at magical thinking I might make this her legacy, but I don’t know what I’d gain by revising her story. If I left out her narcissism, her failure to protect me from my father’s violent temper, and how rarely she took my side, or ignored the fact that my father’s death caused her mostly-manageable drinking habit to turn into an all-consuming addiction that robbed her of everything that once made her special as well as her ability to walk, and me of a parent who I could rely on, I’d been denying myself fundamental aspects of my life and identity

"If I were better at magical thinking I might make this her legacy, but I don’t know what I’d gain by revising her story."

Those who’ve endured a significant loss often say they felt isolated by their anguish and endured pressure, both direct and implied, to “move on” sooner than they wanted or were able. I had the opposite experience. In the aftermath of my mother’s death, so many of my friends wanted to listen to me, comfort me, and cook me food. They expected me to be devastated, and since I wasn’t, I felt I was doing something wrong. I appreciated their effort and thoughtfulness, but I resented how hard it was for people who knew me well to understand how I did or didn’t feel. Though mine is the easier experience, it is also less common, and I’ve learned that many people find my reaction repugnant or offensive, so I end up feeling just as isolated as everyone else.

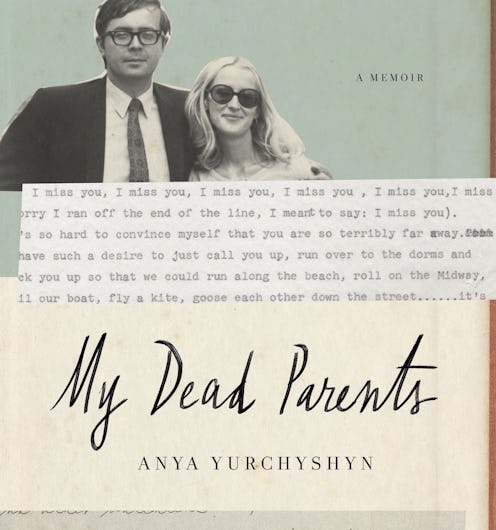

My Dead Parents by Anya Yurchyshyn, $14.85, Amazon

Mother’s Day, like the rest of my life, became so much easier once my mother died. When she was alive, it forced to acknowledge the person she’d become and accept that she didn’t want to get better. I’d call her multiple times that day; if she eventually answered she’d ask why I was calling her at 3:00 am and I’d explain that actually, it was 3:00 pm. She’d dismiss my concerns and say that she hadn’t gotten any of the worried messages that I regularly left. She’d ask me questions but trail off before she finished them; when I asked about hers, she talked about her favorite TV shows. Seeing her world, which was once limitless and thrilling, shrink to the size of her bed was so depressing. I am grateful that I no longer have to make those phone calls, call her friends when I went weeks without hearing from her, or pretend, as she did, that we had a good, loving, relationship. She’d always liked to preform happy family and readily embellished stories I’d long know by heart so seemed more important, brilliant, or deserving of pity. I didn’t explain that I found her grand proclamations — "I was destined to be your mother” — offensive and hurtful because she didn’t seem to care about my life or the person I was becoming or consider that, instead of being breathlessly seduced by her fantasies, I’d wondered what terrible things I’d done in a previous life to make her my destiny in this one.

"Mother’s Day, like the rest of my life, became so much easier once my mother died. When she was alive, it forced to acknowledge the person she’d become and accept that she didn’t want to get better."

I encounter versions of the women I observed on Facebook every Mother’s Day, people who feel excluded — even attacked — by this holiday. Their grief makes me feel the same way. Watching them mourn the mother they lost reminds me that I don’t mourn for my own. I’ve found that having nothing to grieve can itself produce grief, a sadness that stems from longing for the mother I didn’t have, the one I’d badly wanted, the love and support I didn’t receive. I’ve also found that this pain comes with an opportunity to gain as much as I lost. Though I didn’t experience the joys that define many mother-daughter relationships, I have a buoyant freedom that feels like rebirth and refuses to be weighed down.