Books

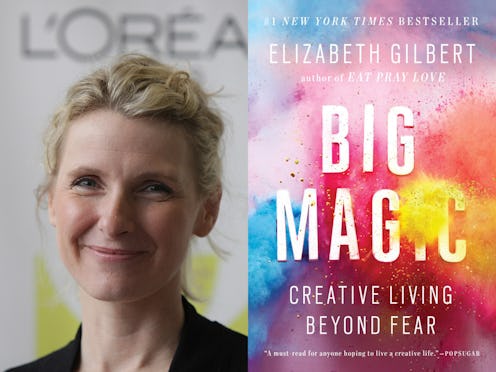

This Passage From 'Big Magic' Forced Me To Completely Rethink How I Write

There is this idea we all have of what genuine artists are supposed to look like, of how they are supposed to act. Maybe they are supposed to be tortured, either by a painful past, a dependency on drugs and alcohol, or by art itself. To be successful, to be legitimate, an artist has to suffer at some point — or at least that is how the romanticized myth of creative living goes, at least the way I've heard it. As someone who has always longed to be a Serious Author, I have spent a lot of time searching for these signs of authenticity in my own life, because according to the most commonly accepted tropes about artists, they are the true markers of success. But then I read Elizabeth Gilbert's book about creativity, and one passage from Big Magic shattered my perception of what an artist is supposed to be. It turns out, the "tortured" part of Tortured Artist is optional, and the artist part is a whole lot easier without it.

Published in 2015, Big Magic is a thoughtful and encouraging guidebook for living a creative life without fear and suffering. Over the course of six sections — "Courage," "Enchantment," "Permission," "Persistence," "Trust," and "Divinity" — Gilbert shares her personal theories and beliefs about creativity and how best to embrace it when it hits. It includes personal anecdotes about the author's own successes and struggles alongside thoughtful tips for recognizing inspiration, maintaining balance, facing fear, and finding fulfillment in whatever creative endeavor you choose.

Big Magic's practical purpose is not to teach readers how to write a bestselling novel or compose the perfect poem or make serious art — all things Gilbert believes you are capable of doing, by the way. Its purpose is to show readers how to transcend the things that stand in the way of creative living. One of the biggest obstacles for me? The myth of the Tortured Artist.

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert, $12, Amazon or Indiebound

According to Gilbert, we have two options when inspiration knocks on our door. We can reject it, pass on the idea it presents, or accept it and get ready to engage with it. If we choose to accept, to enter into what the Eat, Pray, Love author calls a "creative contract," we have to be careful to avoid the most common one of all: the creative contract of suffering.

As Gilbert explains it, "This is the contract that says, I shall destroy myself and everyone around me in an effort to bring forth my inspiration, and my martyrdom shall be the badge of my creative legitimacy."

Seeing the description written out on the page, reading the characterization that followed — an artist who drinks heavily, ruins personal relationships, sews self-doubt and self-hate, feeds off of jealous and envy, swings dramatically between conceit and self-pity, resents their creativity, and is never satisfied with their work — was a kind of wake up call. I mean really, if I ever saw that job description in the Help Wanted section of the paper, would I even want to apply? Of course not, but that has never stopped me from trying to fit my own life into the Tortured Artist mold.

It's true that this creative contract of suffering is not a pretty picture, and yet it is the one so many aspiring artists, myself among them, strive to look like. What other options do we have? How can we ever earn our "badge of creative legitimacy" without enduring all of that suffering our idols did?

Gilbert offers another suggestion, a better suggestion: "You can receive your ideas with respect and curiosity, not with drama and dread."

As the author explains in Big Magic:

"You can clear out whatever obstacles are preventing you from living your most creative life, with the simple understanding that whatever is bad for you is probably also bad for your work. You can lay off the booze a bit in order to have a keener mind. You can nourish healthier relationships in order to keep yourself undistracted by self-invented emotional catastrophes. You can dare to be pleased sometimes with what you have created. (And if a project doesn’t work out, you can always think of it as having been a worthwhile and constructive experiment.) You can resist the seductions of grandiosity, blame, and shame. You can support other people in their creative efforts, acknowledging the truth that there’s plenty of room for everyone. You can measure your worth by your dedication to your path, not by your successes or failures. You can battle your demons (through therapy, recovery, prayer or humility) instead of battling your gifts – in part by realising that your demons were never the ones doing the work, anyhow. You can believe that you are neither a slave to inspiration nor its master, but something far more interesting – its partner – and that the two of you are working together towards something intriguing and worthwhile. You can live a long life, making and doing really cool things the entire time. You might earn a living with your pursuits or you might not, but you can recognise that this is not really the point. And at the end of your days, you can thank creativity for having blessed you with a charmed, interesting, passionate existence."

I don't know about you, but to me, Gilbert's vision of a creative life sounds a lot better than the myth of the Tortured Artist I've been buying into most of my life. I would much rather have the support of my loved ones than burn my relationships for the sake of a story, and living without constant shame and bitterness and anger certainly seems appealing. Gilbert's vision sounds a lot more practical, too. Of course, this doesn't mean that you should reject your suffering; not at all. But to a certain extent, it's about being honest with yourself — about how you feel, what you've endured, and how you have coped.

Of course, this euphoric idea of what an artist's life can be, of what Gilbert thinks it should be, might not be as easy, but when has creative living ever been simple? Despite its difficulty, though, I'm more inclined to believe this road less traveled will indeed make all the difference.